- Step-by-step procedures

- Estimated completion time

- Resources labeled by icons

direct teachers to the piece of content named in the procedures

direct teachers to the piece of content named in the procedures - Print-ready pages as indicated by

are available as PDFs for download

are available as PDFs for download  located above “KEY WORDS” to access student handouts and vocabulary in Spanish

located above “KEY WORDS” to access student handouts and vocabulary in Spanish- Subtitles/CC [ found in

] available in Spanish and English for testimonies

] available in Spanish and English for testimonies

In honor of Universal Pictures’ rerelease of Schindler’s List, Echoes & Reflections has created a short, classroom-ready Companion Resource, that will help educators to provide important historical background and context to the film, as well as explore powerful true stories of rescue, survival, and resilience with their students.

Additionally, the following videos, recorded at Yad Vashem, feature Schindler survivors who speak of the impact Oskar Schindler had on their lives.

EVA LAVI TESTIMONY

NAHUM & GENIA MANOR

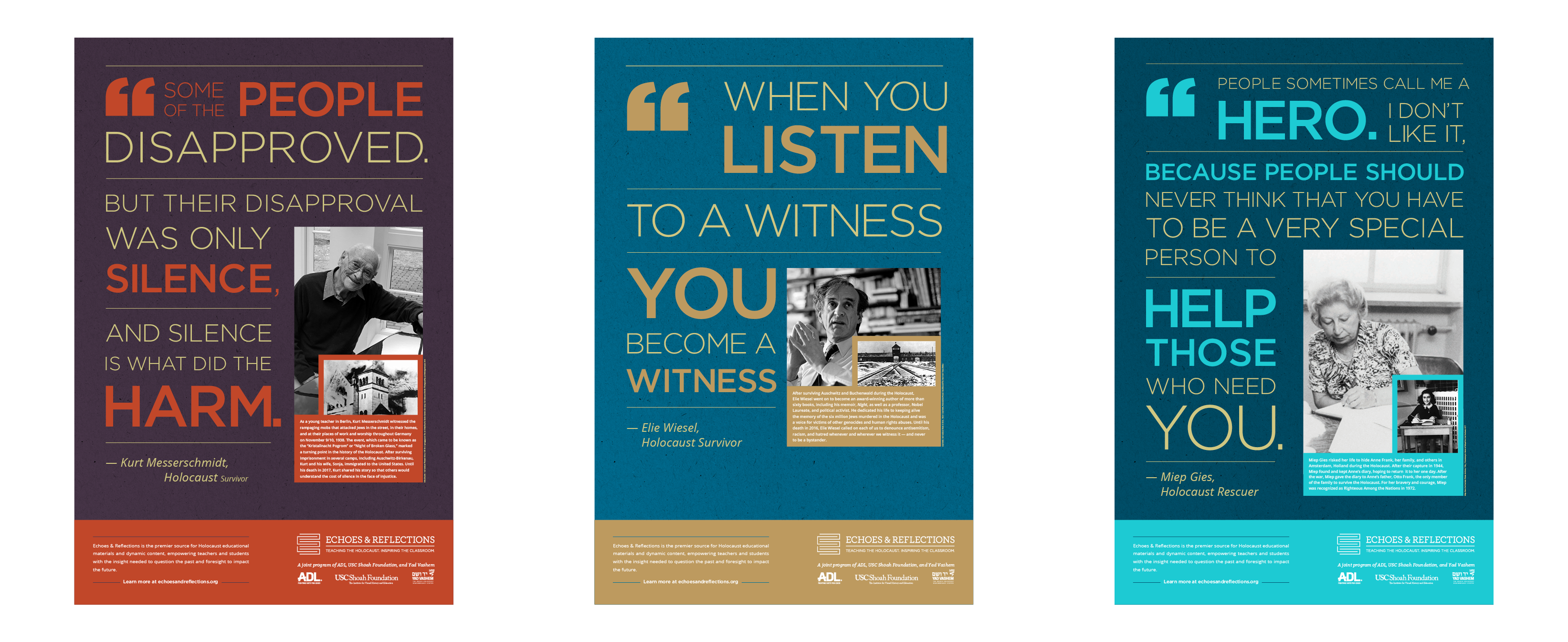

The posters feature the powerful words and experiences of Holocaust survivor and memoirist Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor Kurt Messerschmidt, and Anne Frank rescuer, Miep Gies. Each poster promotes meaningful conversation and reflection in the classroom, whether in person or in a virtual setting, and inspires students with powerful human stories of the Holocaust that can continue to guide agency and action as a result of studying this topic.

To support you in these efforts, we have also compiled several suggested classroom activities from teachers in our network that may be of use and interest.

Please fill out the form below to access and download your PDF posters.

USC Shoah Foundation’s first podcast, We Share The Same Sky, seeks to brings the past into present through a granddaughter’s decade-long journey to retrace her grandmother’s story of survival. We Share The Same Sky tells the two stories of these women—the grandmother, Hana, a refugee who remained one step ahead of the Nazis at every turn, and the granddaughter, Rachael, on a search to retrace her grandmother’s history.

A self-portrait of Rachael while she is living on a Danish farm that is owned by the granddaughter of Hana’s foster mother from World War II. Photo by Rachael Cerrotti, 2017

In order to enhance its classroom use, USC Shoah Foundation and Echoes & Reflections have created a Companion Educational Resource to support teachers as they introduce the podcast to their students. This document provides essential questions for students, as well as additional resources and content to help build context and framing for students’ understanding of the historical events addressed in the podcast.

Access to the podcast, as well as additional supporting materials—including IWitness student activities, academic standards alignment, and general strategies for teaching with podcasts—can all be found at the We Share The Same Sky page in IWitness.

Note: Due to the subject nature, the podcast is appropriate for older students, grades 10-12. As always, teachers should review the content fully in advance to determine its appropriateness for their student population.

After many years of research and digitizing the archive her grandmother left behind, Rachael set out to retrace her grandmother’s 17 years of statelessness. Her intention was to travel via the same modes of transportation and to live similar style lives as to what her grandmother did during the war and in the years after. That meant that when she got to Denmark, she moved to a farm. Rachael moved in with the granddaughter of her grandmother’s foster mother from World War II and traded her labor for room and board as Hana once did. This picture is from that first visit in the winter of 2015. Since this time, Rachael has spent many more months living on this farm. It is owned by Sine Christiansen and her family. Sine is the granddaughter of Jensine, one Hana’s foster mother from World War II. Photo by Rachael Cerrotti, 2015

A self portrait of Rachael overlooking the exact spot in Southern Sweden where her grandmother’s refugee boat came to shore in 1943. Photo by Rachael Cerrotti, 2016

English

English Español

Español

– ROMÉO DALLAIRE, FORCE COMMANDER OF UNAMIR (UNITED NATIONS ASSISTANCE MISSION FOR RWANDA)

Below is information to keep in mind when teaching the content in this unit. This material is intended to help teachers consider the concept of genocide, how to foster empathy with the victims who were persecuted, how to better understand the mechanisms used and the process of the escalation of hate that can lead to genocide, and how the legacies of genocides are created, memorialized, and remembered.

|

|

This unit is shaped by four fundamental questions that have shaped each lesson: What is genocide? Who were the people before they became victims? How did genocide occur? How do we remember a genocide? In asking these questions about four genocides of the 20th century, the purpose of this unit is to encourage critical thinking in students to explore the concept of genocide and analyze some of the common themes seen across multiple genocides. This unit challenges students to find value and meaningful lessons in the study of genocide and how memory and the understanding of genocides of the past can empower them to act against hatred today.

- What is genocide? Why do we study about it? Why should we study it?

- Was the Holocaust an example of genocide? What are some of the parallels between the genocides studied in this unit and how are they different from the Holocaust?

- Who were the victims of the genocides in the 20th century studied in this unit? Why is it important to learn about the victims of genocide as they were, before they became victims?

- How does a society ostracize a group and make it acceptable to commit atrocities against them? How does media, propaganda and fear capitalize on long roots of preexisting hatred and enmity to contribute to creating conditions where genocide can occur?

- How do documentation, including testimony, the law, and remembrance of genocide benefit human civilization?

- How does the term “genocide” fail, or succeed, in capturing the tremendous tragedy and loss of human life, especially against the backdrop of other human rights violations and mass atrocities? Since every genocide is different, what is the importance of having one word to use as an umbrella term?

|

|

ACADEMIC STANDARDS

Academic and SEL Standards View More »

School Library Standards View More »

View More »

View More »

Testimony Reflections View More »

View More »

ACADEMIC STANDARDS

Academic and SEL Standards View More »

School Library Standards View More »

View More »

View More »

Reflexiones de los Testimonios Ver más »

View More »

90-120 minutes

90-120 minutes

LESSON 1: What is the Crime of Genocide?

| 1 | Students learn that they will embark upon a study of genocide, a term that has many facets but can be difficult to define. Students perform a self-examination of their knowledge of genocide by completing the Learn and Confirm Chart. |

| 2 | Students engage in a think-pair-share with a classmate about their completed Learn and Confirm Chart. As a whole group, the class discusses what they know about genocide and their main questions. The questions are recorded on chart paper and posted for the duration of the unit. |

| 3 | Students watch the video, What is Genocide? As they watch, they take notes about the different experiences mentioned and major themes to explore. The entire class discusses these and they are added to the posted chart paper as areas to explore later in the unit. |

| 4 | Students learn that the term genocide was coined by Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1944. Individually or in small groups, students read the handout, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. As they review, students annotate the text and record information that helps them to understand the many ways perpetrators may enact genocide on a victim group. |

| 5 | Students complete a jigsaw activity examining the Armenian Genocide, the Holocaust, the Cambodian Genocide and the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda. Students utilize the Genocide handout, their Learn and Confirm Chart, and the Axis Rule in Occupied Europe handout to create an explanation for whether and why each of these events should be considered a genocide (Armenia, Holocaust, Cambodia, Rwanda). Questions to guide this activity include: |

Genocide View More »

Armenia View More »

Holocaust View More »

Cambodia View More »

Rwanda View More »

View More »

Genocidio Ver más »

Armenio Ver más »

El Holocausto Ver más »

Camboya Ver más »

Ruanda Ver más »

View More »

|

|

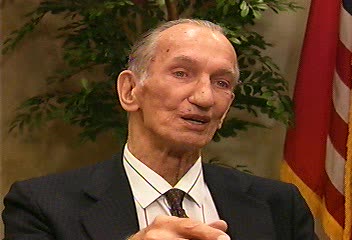

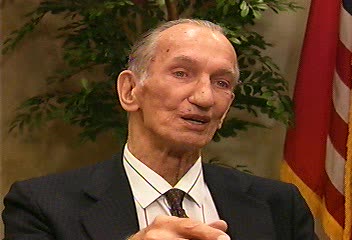

| 6 | Students are introduced to [L]Ben Ferencz[/L]. As a class or in small groups, students interact with Ben through Dimensions in Testimony. Students ask Ben some of these sample questions, as well as ones they create on their own: |

IWITNESS ACTIVITY

IWITNESS ACTIVITYDimensions in Testimony – Ben Ferencz

here »

IWITNESS ACTIVITY

IWITNESS ACTIVITYWhat is Genocide?

here »

IWITNESS ACTIVITY

IWITNESS ACTIVITYDimensions in Testimony – Ben Ferencz

here »

IWITNESS ACTIVITY

IWITNESS ACTIVITYWhat is Genocide?

here »

|

|

| 7 | As a summative task, students are challenged to contemplate the efficacy of society and international law in preventing genocide. In pairs, students read the poem, When Evil-Doing Comes like Falling Rain, from poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht, and discuss the following questions: |

- How does the poem build from the first line to the last? What do you think the significance of that is?

- What does the author want the reader to think, do, and understand after having read this poem?

- How does this poem help us understand the crime of genocide and how individuals, society, and the law have largely failed to prevent it?

60-90 minutes

60-90 minutes

LESSON 2: What do Genocides Destroy?

This lesson introduces students to the people before they became victims of genocide. It highlights their interests, hopes, dreams, and humanity. This glimpse into their worlds allows students to see them as individuals, creating empathy and deepening understanding of the diversity of life in their respective countries. At the end of the lesson, students begin to examine the chasms that existed in society and the small but meaningful ways in which these groups were vulnerable to ostracization and acts of discrimination.

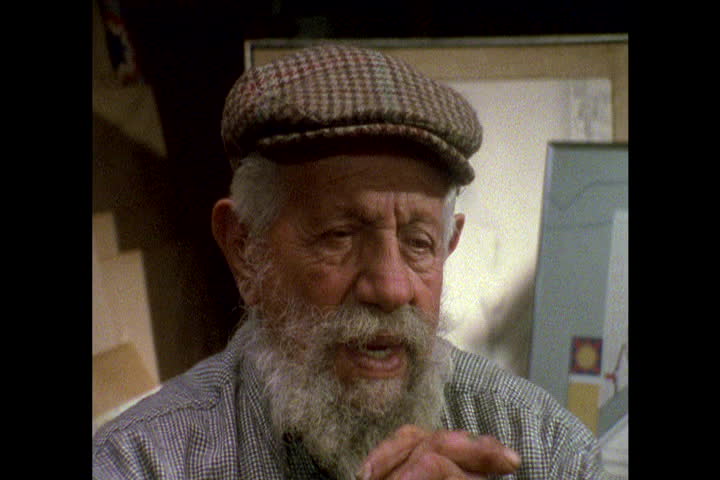

| 1 | Students learn that victims of genocide do not live their lives in the shadow of the impending catastrophe. They are people with various interests, values, hobbies, jobs, who seek to live fulfilling lives. They don’t know what is to happen in their futures. Students are introduced to two survivors of different genocides, Armenian survivor [L]Jirayr Zorthian[/L], and Tutsi survivor [L]Live Wesige[/L], and watch their testimonies. As they watch the clips, students take notes on the Life Before Genocide Graphic Organizer. |

| 2 | In small groups, students read the handout, Life Before Genocide, and complete the Life Before Genocide Graphic Organizer and discuss the questions at the bottom. |

Life Before Genocide Graphic Organizer View More »

Life Before Genocide View More »

| 3 | Students participate in a whole class discussion, sharing their reflections from the victims and discussing the following questions: |

- Why is it important to learn about the lives of victims of genocide before they became victims?

- How can understanding who these people were help us to recognize the magnitude of genocide and the total rupture it causes to victim groups?

| 4 | Students learn that even before genocide occurs, there is often an undercurrent within the respective societies that seeks to ostracize victim groups in small but meaningful ways that helps foment the genocide, including overt and sometimes violent actions. |

| 5 | Students learn that a stereotype is “an oversimplified generalization about a person or group of people without regard for individual differences.” In small groups, students identify different stereotypes they have observed and experienced. Then, they discuss the following questions:

|

View More »

View More »

| 6 | Students watch the testimonies of [L]David Faber[/L], [L]Sara Pol-Lim[/L], and [L]Kizito Kalima[/L]. As they watch the clips, students take notes on the Testimony Reflections handout. After viewing the clips, the class discusses the following questions: |

- How was each person ostracized? How were the differences, real or imagined, of each person emphasized in order to separate them from the larger group? How did that make them feel?

- How did the actions of others, including neighbors and people in authority, contribute to the isolation of the victims?

- How did the schools, communities, and society as a whole suffer from the exclusion of the victim groups? What was lost by rejecting them?

| 7 | Students are informed that victims of persecution were often marked to further separate them from larger society. Jews had been marked in different ways over thousands of years, and during the Holocaust, some were forced to wear the Star of David on their clothes. In pairs or triads, students analyze the artwork, Yellow, 1962-2006, by Samuel Bak. |

- What do you see in the artwork? How does Bak use color and texture to convey his feelings about being forced to wear the Yellow Star?

- What is the tone of the artwork? What are some emotions the artist is conveying?

- Connect this artwork to the testimonies of David, Sara, and Kizito. How does this work of art expand our understanding of the pain felt by groups that are ostracized from their communities?

120-150 minutes

120-150 minutes

LESSON 3: How do Genocides Destroy?

In this lesson, students are confronted with the escalation of hate, which when left unchecked, can lead to the conflagration of genocide. Students are to consider the power of the media and propaganda to ignite pre-existing hatreds, dehumanize the victims, and encourage average citizens and neighbors to turn against their fellow persons. Teachers should exercise caution in examining the hate speech that was used to persuade and mobilize the masses so as not to cause harm nor foster similar hatreds in their students. Finally, students confront the horrors of genocide and how, even amidst extreme persecution, victims struggled to maintain their humanity.

| 1 | Students are informed that they will learn about the escalation of hate, the impact that the leaders of governments have on inciting genocide, the power of the media to carry that message, and the fertile ground that makes the public receptive to these messages of hate. In pairs or small groups, students read the handout, Dangerous Policies of Genocidal Regimes, and answer the questions that follow. |

| 2 | Students watch the video, Words that Kill, which talks about the power of propaganda and the radio to incite genocide in Nazi Germany and Rwanda. Next, the class discusses the following questions: |

|

|

| 3 | Students examine the images in the Examples of Propaganda handout. In pairs, students discuss the following questions: |

- What do you see in each image? What is the propagandist trying to make viewers feel?

- Why is the concept of a parasite or something that can make us sick a common propaganda technique? How does that stoke fear in a population?

- How did propaganda messages like these and stereotypes used by the perpetrators dehumanize their victims? What might have been the effects of such dehumanization for both individuals and victim communities?

| 4 | Students watch the testimonies of [L]Marion Pritchard[/L], [L]Freddy Mutanguha[/L], and [L]Arshag Dickranian[/L]. As they watch the clips, students take notes on the Testimony Reflections handout. After viewing the clips, the class discusses the following questions: |

Testimony Reflections View More »

Reflexiones de los Testimonios Ver más »

|

|

| 5 | As a summative task, students write a brief journal entry reflecting on this quote from Marion: “It shows that even with people who want to resist propaganda, it still has an effect.” |

| 6 | Students watch the testimonies of [L]Freddy Mutanguha[/L], [L]Elise Taft[/L], [L]Barbara Fischman Traub[/L], and [L]Theary Seng[/L] and are confronted by the knowledge that genocide is often perpetrated by neighbors and those once considered friends. Discuss some or all of the following questions: |

- What are some of the emotions, voice intonations, and body language cues that you noticed in the clips? Why are these cues an important part of understanding and fostering empathy with the survivors?

- Based on their actions, the neighbors knew what was happening or even participated. In each scenario, describe what the neighbors were doing and the effect it had on the individuals who were targeted.

- How is genocide often a very personal and intimate experience for the victims? Does this surprise you? How does it affect your understanding of how genocides are perpetrated?

| 7 | In small groups, students review, discuss, and complete the Photographic Case Study Graphic Organizer about The Conflagration in Photos handout. Students thoroughly analyze each photograph, one photo at a time. When finished, each photo is projected, students review their completed graphic organizers, and discuss the following questions: |

View More »

Photographic Case Study Graphic Organizer View More »

The Conflagration in Photos View More »

View More »

Organizador Grafico de un Estudio de Caso Fotografico Ver más »

La Conflagracion en Fotos Ver más »

- What is the tone(s) of the photograph? How would you describe the conditions endured by the people in the photograph?

- What do you notice about the faces, disposition, and body language of the people in the photographs?

- How do these photos help you understand the suffering of the people?

- How can these photos help you understand the tragedy of genocide?

| 8 | In small groups, students examine the Humanity in Artifacts handout and complete the questions found in the Artifact Reflection handout. |

| 9 | As a summative task, students discuss the following questions together: |

- How do the testimony, photographs, and artifacts help us better understand what happened to the victims of genocide?

- Why is it important to affirm the humanity of the victims?

- How does this approach help us better understand the loss, resistance, and resilience experienced by the victim group?

60-90 minutes

60-90 minutes

LESSON 4: Aftermath

This lesson considers what happens after a genocide has occurred. There is no blueprint of how to respond to genocide but after each of the genocides explored in this unit, there were criminal trials against some of the perpetrators. These trials brought various levels of justice and accountability, while collecting vast amounts of documentation. Students are introduced to the concept of denying a genocide, even against the factual documentation. Next, students will explore the roles of memorials and museums to create and protect the legacy of a genocide. Lastly, students are then asked to reflect on what they have learned and why it is important to study genocide.

| 1 | Students watch the testimonies of [L]Freddy Mutanguha[/L] and [L]Theary Seng[/L]. Then, students discuss the following questions: |

|

|

| 2 | Students learn that often the last stage of genocide is denial. Today, there are many people who deny the Holocaust as well as many that deny the Armenian Genocide, including in official statements by the Republic of Türkiye. Students view the video, Holocaust Denial, Explained and the testimony of [L]Haigas Bonapart[/L]. |

View more »

View more »

Students learn that often the last stage of genocide is denial. Today, there are many people who deny the Holocaust as well as many that deny the Armenian Genocide, including in official statements by the Republic of Türkiye. Students view the video, Holocaust Denial, Explained and the testimony of Haigas Bonapart (bio) . ![]() In small groups, students discuss the following questions:

In small groups, students discuss the following questions:

- Why do you think the final stage of genocide is denial? Why would perpetrators seek to deny a genocide? Why would people decades later continue to deny?

- How does denial affect the victim survivors of genocide? How does this action of denial continue to harm victims and all of society?

- What are some ways we can combat denial and the weaponization of lies?

| 3 | Students watch the testimony of [L]Brigitte Altman[/L]. The handout, Memorials and Museums of Genocide is distributed and students complete the Memorials and Museums Graphic Organizer in small groups. After they complete the graphic organizer, students discuss the following questions: |

Memorials and Museums of Genocide View more »

Memorials and Museums Graphic Organizer View more »

Memoriales y Museos Sobre Genocidio Ver más »

Memoriales y Museos Organizador Grafico Ver más »

|

|

| 4 | As a summative task, students watch the testimony of [L]Jan Karski[/L]. Students reflect on his testimony and what they have learned by responding to these questions in a journal entry and then discussing them with a partner or as a whole class: |

- Jan Karski states that “great crimes start with little things” and then goes on to give examples of things people should not do. How does the memory of genocide inspire us to oppose the little things Karski warns us about?

- What from this brief study of genocide will you remember most and why? What are you curious to learn more about?

- Why is studying genocide important? What lessons can be learned from studying genocides?

The ideas below are offered as ways to extend the lessons in this unit and make connections to related historical events, current issues, and students’ own experiences. These topics can be integrated directly into Echoes & Reflections lessons, used as stand-alone teaching ideas, or investigated by students engaged in project-based learning.

| 1 | Raphael Lemkin spent his life advocating for the concept of genocide to be accepted and codified into international law. He believed that belonging to a group was an essential way of identity and that the destruction of a social group is a societal evil. He argued that genocides had changed the course of human history by eradicating cultures, peoples, and forcing mass migrations. Watch this trailer from the movie about his life, Watchers of the Sky, and conduct further research into the life of Lemkin. Examine the use of the word genocide since he coined the term and investigate its misuse/appropriation. |

| 2 | Students research local museums and create a multimedia presentation analyzing the role of museums in honoring, remembering, and educating the population about genocide, human rights violations, and other aspects of social justice. |

| 3 | Visit IWitness (iwitness.usc.edu) to access additional testimonies, resources, an learning activities about the genocides discussed in this unit as well as additional genocides and mass atrocities, including the Anti-Rohingya Mass Violence, the South Sudan Civil War, and the Guatemalan Genocide. |

| 4 | Students watch Eva’s Stories and write an essay about the life of Eva Heyman. Students should analyze the artistic decision to use Instagram to tell her story and whether it is appropriate to use this platform for this topic. Students should also explore the role of different mediums to tell the human story of genocide and the advantages and disadvantages to these artistic expressions. |

| 5 | Students create a poster or other large visual about a genocide answering the following questions and share with their classmates and the larger school community:

|

| 6 | Students are confronted with Official Government Correspondences that show knowledge of genocide by leaders who then failed to take action to prevent or stop a genocide from occurring. Students should utilize Echoes & Reflections Timeline of the Holocaust with the United States Holocaust Memorial and Museum’s History Unfolded project to research how certain events were reported in their local newspapers. Students contemplate how genocide can be prevented, from individuals to groups to country leaders to foreign nations. What are some actions students can take to bring humanity closer to the promise of “Never Again”? |

bystanderCambodian GenocideCaricatureCollaborationContemporary antisemitismCrimes Against HumanityCUP – Committee of Union and ProgressDeath marchDehumanization