- Step-by-step procedures

- Estimated completion time

- Resources labeled by icons

direct teachers to the piece of content named in the procedures

direct teachers to the piece of content named in the procedures - Print-ready pages as indicated by

are available as PDFs for download

are available as PDFs for download  located above “KEY WORDS” to access student handouts and vocabulary in Spanish

located above “KEY WORDS” to access student handouts and vocabulary in Spanish- Subtitles/CC [ found in

] available in Spanish and English for testimonies

] available in Spanish and English for testimonies

In honor of Universal Pictures’ rerelease of Schindler’s List, Echoes & Reflections has created a short, classroom-ready Companion Resource, that will help educators to provide important historical background and context to the film, as well as explore powerful true stories of rescue, survival, and resilience with their students.

Additionally, the following videos, recorded at Yad Vashem, feature Schindler survivors who speak of the impact Oskar Schindler had on their lives.

EVA LAVI TESTIMONY

NAHUM & GENIA MANOR

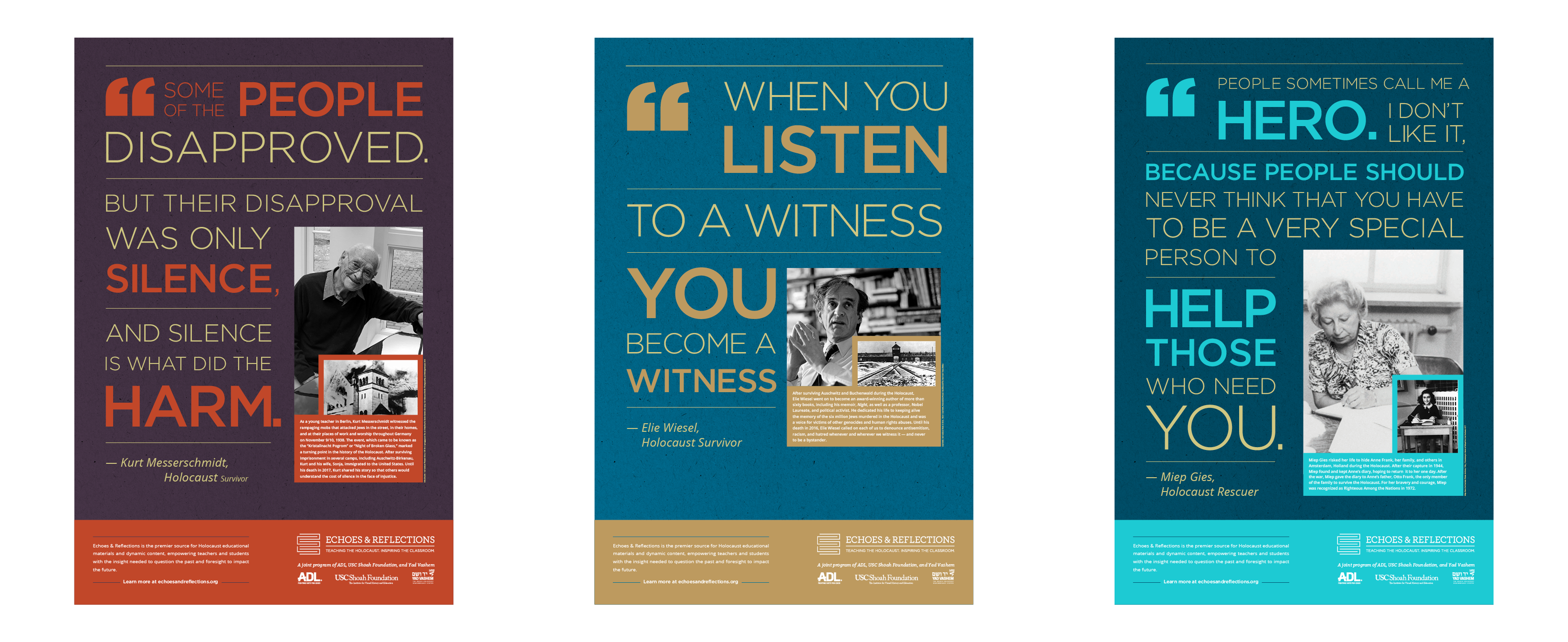

The posters feature the powerful words and experiences of Holocaust survivor and memoirist Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor Kurt Messerschmidt, and Anne Frank rescuer, Miep Gies. Each poster promotes meaningful conversation and reflection in the classroom, whether in person or in a virtual setting, and inspires students with powerful human stories of the Holocaust that can continue to guide agency and action as a result of studying this topic.

To support you in these efforts, we have also compiled several suggested classroom activities from teachers in our network that may be of use and interest.

Please fill out the form below to access and download your PDF posters.

USC Shoah Foundation’s first podcast, We Share The Same Sky, seeks to brings the past into present through a granddaughter’s decade-long journey to retrace her grandmother’s story of survival. We Share The Same Sky tells the two stories of these women—the grandmother, Hana, a refugee who remained one step ahead of the Nazis at every turn, and the granddaughter, Rachael, on a search to retrace her grandmother’s history.

A self-portrait of Rachael while she is living on a Danish farm that is owned by the granddaughter of Hana’s foster mother from World War II. Photo by Rachael Cerrotti, 2017

In order to enhance its classroom use, USC Shoah Foundation and Echoes & Reflections have created a Companion Educational Resource to support teachers as they introduce the podcast to their students. This document provides essential questions for students, as well as additional resources and content to help build context and framing for students’ understanding of the historical events addressed in the podcast.

Access to the podcast, as well as additional supporting materials—including IWitness student activities, academic standards alignment, and general strategies for teaching with podcasts—can all be found at the We Share The Same Sky page in IWitness.

Note: Due to the subject nature, the podcast is appropriate for older students, grades 10-12. As always, teachers should review the content fully in advance to determine its appropriateness for their student population.

After many years of research and digitizing the archive her grandmother left behind, Rachael set out to retrace her grandmother’s 17 years of statelessness. Her intention was to travel via the same modes of transportation and to live similar style lives as to what her grandmother did during the war and in the years after. That meant that when she got to Denmark, she moved to a farm. Rachael moved in with the granddaughter of her grandmother’s foster mother from World War II and traded her labor for room and board as Hana once did. This picture is from that first visit in the winter of 2015. Since this time, Rachael has spent many more months living on this farm. It is owned by Sine Christiansen and her family. Sine is the granddaughter of Jensine, one Hana’s foster mother from World War II. Photo by Rachael Cerrotti, 2015

A self portrait of Rachael overlooking the exact spot in Southern Sweden where her grandmother’s refugee boat came to shore in 1943. Photo by Rachael Cerrotti, 2016

English

English Español

Español

- ELLIS LEWIN, JEWISH SURVIVOR

Below iss information to keep in mind when teaching the content in this unit. This material is intended to help teachers consider the complexities of teaching about the ghettos and to deliver accurate and sensitive instruction.

| 1 | Students may be accustomed to thinking about the concept of a ghetto within the context of U.S. history and African American civil rights. Throughout this unit, help them to distinguish between this understanding of a ghetto and the different reality for Jewish people during the Holocaust. Both notions of ghettos reflect the idea of an unjust separation. In the U.S., ghetto was first used to designate slum areas occupied by poor and immigrant groups, and later – due to African American migration and “white flight” – to describe poor, urban, mostly black communities. Segregation in these communities was not mandated by law, but imposed by poverty and racist policy. Jewish people during World War II were forcibly imprisoned in more than 1,100 ghettos using brutal means of control. These ghettos, which grew from Nazi racial policy and served to isolate and weaken the Jewish populace, were sites of mass suffering and death. |

| 1 | The ghettos in central Poland were established at the outset of World War II, before the “Final Solution” was planned and extermination camps were built. Their principal purpose was to temporarily isolate Jews, pending the formulation of a more definitive solution to the so-called “Jewish problem.” Some Sinti-Roma people were also incarcerated in ghettos in Eastern Europe after they were deported from greater Germany. When the ghettos were formed, a detailed blueprint for carrying out mass murder did not yet exist; rather, death was a side effect of the starvation, disease, and overcrowding in the ghettos. For instance, more than 80,000 Jews died in the Warsaw ghetto alone. It was only in 1941, with the invasion of the Soviet Union, that the Nazis began murdering Jews in a systematic mass fashion, and a project for murdering all Jews began to coalesce. |

| 3 | Students often ask why more Jews did not escape from the ghettos. It is important for students to remember the extenuating circumstances that made it nearly impossible for the vast majority of Jews to flee. |

|

|

This unit provides students with an opportunity to learn about the ghettos established throughout Nazi Europe and understand that the ghettos were one phase in the continuum of Nazi racial policies that sought to solve the so-called “Jewish problem.” Students investigate the conditions in ghettos and how those conditions severely limited Jewish life and led to immense suffering. Using primary source material, students discover that despite severe overcrowding, starvation, disease, and grief, Jews still did their utmost to conduct their lives and retain their human dignity.

- What were the goals of the Nazis in creating the ghettos?

- How did the Nazis isolate and dehumanize the Jewish people in ghettos?

- How did residents respond to the kinds of choices forced upon them in the ghettos?

- How did the Jewish people seek to maintain their humanity in the face of the extreme dehumanization of ghetto life?

|

|

ACADEMIC STANDARDS

Academic and SEL Standards View More »

School Library Standards View More »

View More »

View More »

Testimony Reflections View More »

ACADEMIC STANDARDS

Academic and SEL Standards View More »

School Library Standards View More »

View More »

View More »

Reflexiones De Los Testimonios Ver más »

90-120 minutes

90-120 minutes

LESSON 1: Establishment of the Ghettos and the Jewish Response

In this lesson, students are introduced to the concept of a ghetto and distinguish between historical and contemporary conceptions of ghettos. Through informational texts, photos, visual history testimonies, and other primary source material, students explore the aims of the Nazis in establishing ghettos during the Holocaust, what daily life was like in the ghettos, and how Jewish people responded to the brutal and dehumanizing conditions that they faced.

| 1 | In groups of three, students engage in a “write-around” in response to the phrase, “A ghetto is…” On a sticky note, each student finishes the phrase and passes the note to another group member. Students add to their peers’ notes and continue passing until they get their own note back. The class then discusses the different notions of a ghetto and what this term means within the context of their study of the Holocaust. |

View More »

View More »

| 2 | Students watch testimony clips from individuals who discuss how their lives drastically changed after being imprisoned in the Lodz Ghetto in Poland: [L]Joseph Morton[/L], [L]Leo Berkenwald[/L], and [L]Ellis Lewin[/L]. As they watch the clips, students reflect on ways in which ghettos during the Holocaust differ from their contemporary understanding of the term. In addition, students take notes on the handout, Testimony Reflections, found at the beginning of this unit. |

View More »

IWITNESS ACTIVITY

IWITNESS ACTIVITYInformation Quest: Ellis Lewin

here »

View More »

IWITNESS ACTIVITY

IWITNESS ACTIVITYInformation Quest: Ellis Lewin

here »

| 3 | After viewing the testimony clips, students journal and/or participate in a whole group discussion in response to some of the following questions: |

|

|

| 5 | The handout, The Ghettos, is distributed and the map, Ghettos in Europe, is either distributed or projected. Students form small groups and each group is assigned one of the following categories: (a) The Nazis’ purpose in establishing ghettos; (b) Daily life and conditions in the ghettos; and (c) The Jewish response – how residents coped with ghetto life. Students read the handout and study the map. They annotate and take notes according to their assigned category. |

GHETTOS IN EUROPE

GHETTOS IN EUROPE

Guetos en Europa

Guetos en Europa

| 6 | When students have completed their analysis of the handouts, they form new groups that contain a mix of students who have focused on different categories. In their new groups, students share highlights from their notes and other significant thoughts and ideas. In their groups and/or as a whole class, students discuss some of the following questions: |

|

|

| 7 | The handout, Diary Entry from the Lodz Ghetto, is projected and students read it independently. The excerpt was written by Josef Zelkowicz, a journalist who documented ghetto life and who perished in Auschwitz in 1944. In triads, students contemplate the question posed by Zelkowicz: “Do you have any children at all in the ghetto?” Each group member chooses a quote from the diary entry that they find meaningful and that speaks to Zelkowicz’s question. They take turns sharing their quote and interpreting Zelkowicz’s question. As a class, students discuss the following: |

View More »

Diary Entry from the Lodz Ghetto View More »

To Infinity and Beyond View More »

|

|

| 8 | As a summative task, students respond to the Lodz Ghetto photo by Mendel Grossman, depicting the harsh reality of ghetto life for children. The NOTE is used to provide background on Grossman and the image. Students use the following prompt to guide their work:

|

View More »

View More »

120-150 minutes

120-150 minutes

LESSON 2: Role of the Ghettos - The Lodz Ghetto as a Case Study

In this lesson students investigate the ways in which the Nazis used ghettos to control, isolate, and weaken the Jewish population. They also consider how Jews responded to this oppression and sought to maintain their humanity in the face of severe brutality. Students focus on the Lodz Ghetto in Poland as a case study. They analyze an informational text as well as primary source documents – including diary entries, poems, and testimonies – from Lodz residents.

Note: This lesson uses the Lodz ghetto as a way to tell a larger story. While each ghetto was unique, this lesson uses Lodz as a prism to try and understand why the Nazis confined Jewish people in such an inhumane manner, what methods were used to control them, and how Jewish people responded to the brutality. What happened in Lodz and the decisions made by people who established the ghetto sheds light on larger decisions that were being made elsewhere, even though the Lodz ghetto had its own uniqueness and special historical circumstances.

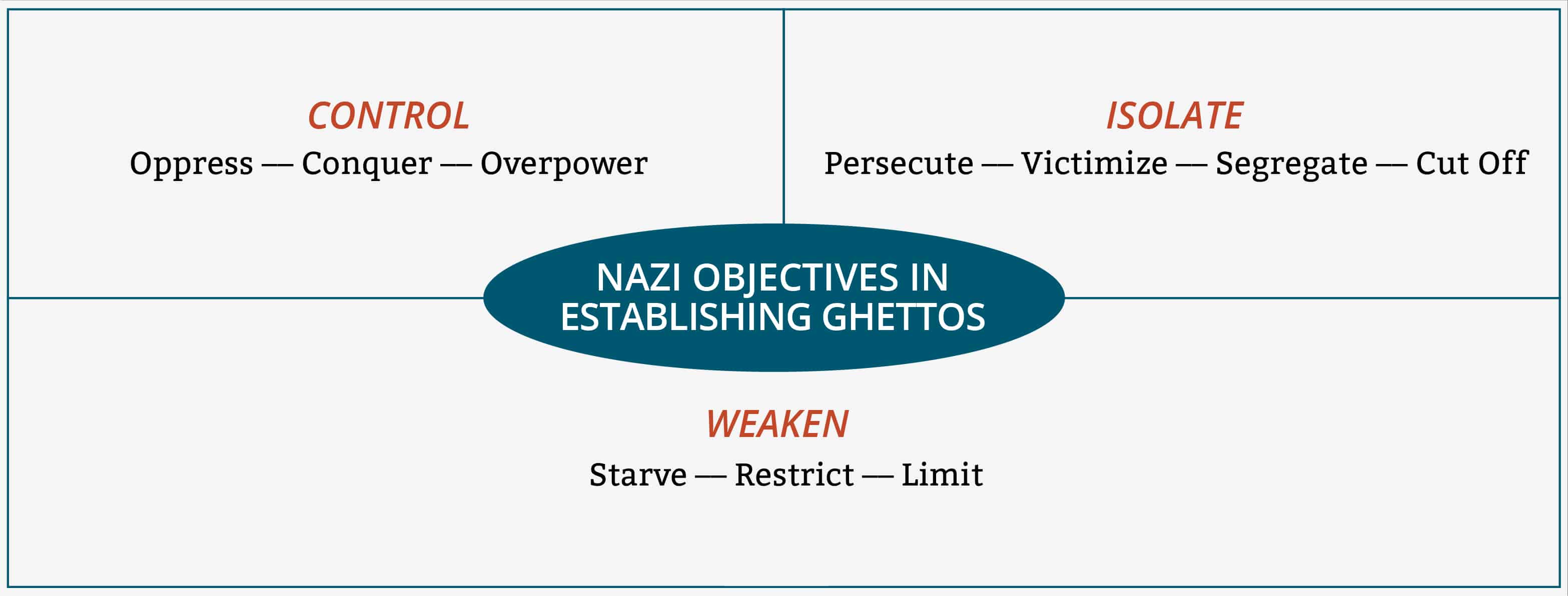

| 1 | Based on their understanding from the first lesson, students write one word on a sticky note that they think best reflects the objectives of the Nazis in establishing ghettos. They post their notes on the board. The class works together to organize the notes by theme into a concept map and to discuss the significance of each theme. For example, see below.

|

| 2 | Students learn that they will focus on one ghetto in this lesson as a case study – the Lodz ghetto in Poland – and that they will apply three themes as they investigate: control, isolate, and weaken. These terms, reflecting core Nazi objectives, are clarified as needed. Students collaborate to create symbols that represent each, which will be used throughout the lesson as they examine sources.

|

| 3 | Students watch testimony clips from individuals who discuss how conditions in the Lodz Ghetto grew dire after confinement there: [L]Milton Belfer[/L] and [L]George Shainfarber[/L]. As they watch the clips, students take notes on the handout, Testimony Reflections, found at the beginning of this unit. They reflect on the themes of control, isolate, and weaken, and use the symbols they created to annotate their observations. |

| 4 | After viewing the testimony clips, students journal and/or participate in a whole group discussion in response to some of the following questions: |

|

|

| 5 | Individually or in pairs, students read The Lodz Ghetto handout. They use different colored highlighters to underscore the lesson themes (control, isolate, weaken) and add the symbols they created where relevant. They annotate the handout with their thoughts and questions about ghetto life. |

| 6 | As a class, students report back on their findings regarding ways in which the Nazis controlled, isolated, and weakened the Jews of the Lodz ghetto. They discuss some of the following questions, citing evidence from the text to support their responses: |

|

|

| 7 | Students watch testimony clips from individuals who reflect on scarcity and being forced to work as children in the Lodz Ghetto: [L]George Shainfarber[/L] and [L]Eva Safferman[/L]. As they watch the clips, students take notes on the handout, Testimony Reflections, found at the beginning of this unit. They reflect on the themes of control, isolate, and weaken, and use the symbols they created to annotate their observations. |

| 8 | After viewing the testimony clips, students journal and/or participate in a whole group discussion in response to some of the following questions: |

|

|

| 9 | The handout, Excerpts from the Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak, is distributed and the class reads the introduction together. Individually or in pairs, students read and annotate the excerpts, highlighting ideas related to the themes of control, isolate, and weaken and adding symbols where relevant. In addition, students reflect on other themes explored throughout the unit, including education, hunger, despair, and hope. In small groups, students share their reactions to the diary excerpts and participate in “The Last Word” exercise as follows:

|

| 10 | As a class, students discuss some of the following questions about Dawid Sierakowiak’s diary entries and support their responses using specific references to the text. |

|

|

| 11 | As a summative task, students respond to one of the following poems: Poem by an Unknown Girl or Poem by Avraham Koplowicz. The poems and background information are read together as a class, and students identify the differences in tone and outlook between the poems (e.g., past vs. future orientation, limited vs. limitless view of time, literal vs.figurative language, despairing vs. hopeful feeling). Students write about one poem using the following prompt to guide their work:

|

Poem by an Unknown Girl View more »

Poem by Avraham Koplowicz View more »

View more »

The ideas below are offered as ways to extend the lessons in this unit and make connections to related historical events, current issues, and students’ own experiences. These topics can be integrated directly into Echoes & Reflections lessons, used as stand-alone teaching ideas, or investigated by students engaged in project-based learning.

| 1 | Visit IWitness (iwitness.usc.edu) for testimonies, resources, and activities to help students learn more about life in the ghettos. |

| 2 | The establishment of ghettos marked the end of freedom of movement for Jews. Write about what freedom means to you in your life and what you think it would mean to lose it. |

| 3 | In challenging times, the importance of remaining hopeful and the belief that one’s situation will improve is crucial. However, this outlook is difficult to maintain over time. Write a reflection in response to the following questions: Do you believe there is a certain point when people begin to lose hope? If so, what do you think that point is? Do you think it is the same for everyone? Has the loss of hope ever happened to you? Have you witnessed it in others? How does a person restore hope? |

| 4 | Use the Echoes & Reflections Timeline of the Holocaust to align events happening in Europe and other parts of the world with Dawid Sierakowiak’s diary entries. Create an overlapping timeline that presents key events in the format of your choice. You can refer to The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak (Oxford University Press, 1996) for additional diary entries. |

| 5 | Artifacts from the ghettos help us to better understand what life was like for the people who lived there. Study the image of the Monopoly Game from the Theresienstadt Ghetto in German-occupied Czechoslovakia. Identify another artifact through online research. Write a brief essay in which you answer the following questions:

|

| 6 | Research the role that music played in the lives of Jews forced to live in one of the following ghettos: Kovno, Vilna, or Lodz. Refer to Yad Vashem’s Music of the Holocaust exhibition as well as other sources. Prepare and share an oral or multimedia report on your findings. |

| 7 | The book, I Never Saw Another Butterfly (Schocken Books, 1993) is a collection of art and poetry by Jewish children who lived in Theresienstadt, a ghetto and transit camp in Czechoslovakia. Read Pavel Friedman’s “The Butterfly,” and study the painting by Liz Elsby that is paired with this poem (or analyze a poem and piece of art of your choosing). Write an essay in which you explore the following questions:

|

Chelmno

concentration campcurfewdeportEinsatzgruppen

extermination camp

liquidatedLodz ghetto

Sonderkommando

Warsaw ghettoZionist