This month we asked members of our educator community to share the stories that have inspired them to teach about the Holocaust. The common thread that binds their reflections is the power of the individual story. Although often born from tragic events, such stories can contribute to building empathy and a strong sense of human connection across generations, countries, faiths, and experiences. What stories have moved you to examine the events of this past? What lessons can be learned from these narratives?

George Bevington is a 9th & 11th Grade English teacher at Holy Innocents’ Episcopal School in Atlanta, Georgia.

One of my favorite accounts of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust is the memoir of Hermann Wygoda, In the Shadow of the Swastika. This story appeals to me because of the coolness and poise Wygoda displayed under the extreme threat of getting caught. Because he could speak both Polish and German, Wygoda was able to pass as a Volksdeutscher[1] and circumvent the suspicion of the Nazis. He also never gave up and continued to fight on in the face of terrible odds.

I have felt compelled to delve deeper into Wygoda’s story because of his  resilience to continue fighting, but also to fulfilling his duty as a parent after the war when he started a family. Although he settled down to a quiet life in Chattanooga, TN, he carried this bloody, horrific, but ultimately triumphant story around with him for the rest of his life, while living in the midst of his neighbors who had no knowledge of his experiences.

resilience to continue fighting, but also to fulfilling his duty as a parent after the war when he started a family. Although he settled down to a quiet life in Chattanooga, TN, he carried this bloody, horrific, but ultimately triumphant story around with him for the rest of his life, while living in the midst of his neighbors who had no knowledge of his experiences.

I was inspired by Wygoda’s story and other partisan’s accounts to create a lesson that details his experiences as well as the experiences of the Bielski brothers during World War II. My students are quite astonished that the literature about these partisans comes from eyewitness accounts and personal diaries. In particular, Wygoda’s interactions with other partisan groups inspires a lot of discussion with my students. They often reflect on how although many of these groups may not have been on good terms, or even outright enemies, during peace time, the common enemy in the German Army pulled them together. My students are surprised that resistance was not only possible, but in some cases, led to freedom despite terrible odds and the might of the German Army.

What hooks the students’ attention the most is the bravery of these fighters, and the irony of the decision they made to fight back, given the alternative. Throughout the unit and especially near the end, as the outcome of the war becomes inevitable, the students’ enthusiasm grows daily for Wygoda and the Bielskis’ triumphs over the Nazi Army. Fascinating stories with a lot of suspense!

[1] Nazi term, literally meaning “German-folk,” used to refer to ethnic Germans living outside of Germany.

Rachel Herman is the Content Specialist for Education at USC Shoah Foundation – The Institute for Visual History and Education and is the Institute’s Echoes & Reflections partner lead. Rachel was the Holocaust Educator at the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh from 2013 – 2017.

In the United States, Clara Barton is remembered for her work as a nurse during the Civil War and for establishing the American Red Cross. In Armenia, Clara is remembered for a relief effort that saved over 50,000 Armenians. Clara Barton Our Angel, Too, tells her story in a clear, concise narrative—with text in Armenian and in English—and through colorful illustrations. My favorite quote from the book is, “Even though the Armenian people lived far from the United States, Americans understood that all people share a common humanity.” This idea of common humanity is woven throughout the story, and this book is a great way to get students  to focus on the importance of empathy, acceptance, and altruism. I would have loved this book as a child!

to focus on the importance of empathy, acceptance, and altruism. I would have loved this book as a child!

Reading this book, I was reminded of a quote by Pastor Andre Trocme, a rescuer during the Holocaust, who said, “I do not know what a Jew is. I know only human beings.” Clara didn’t know Armenians, she knew human beings. She heard about people in need and did what she could to help them. Having empathy and seeing people as human beings, full stop, is what I aspire to do. As the Echoes & Reflections Partner lead for USC Shoah Foundation, the testimony I work with on a daily basis helps me empathize with and learn from people of all different backgrounds, ethnicities, and religions. I am grateful for this opportunity and for the resources we have available that constantly expand my worldview.

Dunreith Kelly Lowenstein is an Echoes & Reflections facilitator, a former English/History teacher, and a Fulbright Specialist with the U.S Department of State.

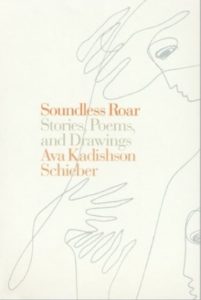

In July 2003, I was invited to attend a presentation by Ava Kadishson Schieber, a Holocaust survivor from the former Yugoslavia. I had no idea when I accepted the invitation that it would lead to an ongoing relationship with the speaker. Ava spent four long years hiding in an unheated shed between the chickens and the pigs on a farm outside of Belgrade. Her experiences during the years prior to, during, and immediately after World War II were harrowing and challenging. But growing up in a loving, multi-generational family greatly contributed to her positive outlook on life and subsequent ability to survive, and even thrive, in the face of the odds she frequently encountered. Her resilience and physical and mental strength  were obvious as she spoke. Completely mesmerized, I introduced myself after the talk to express my gratitude to her for sharing her story. She gave me her calling card with one of her line drawings and address and invited me to visit her home.

were obvious as she spoke. Completely mesmerized, I introduced myself after the talk to express my gratitude to her for sharing her story. She gave me her calling card with one of her line drawings and address and invited me to visit her home.

I immediately read her book Soundless Roar; Stories, Poems and Drawings, a work which includes stories about her life before the war, and could see how wonderful it would have been to use during my twelve years of teaching English/History to middle and high school students. (I had recently left the classroom and begun a career in professional development).

I have since had the pleasure of accompanying Ava dozens of times as she speaks to middle and high school students, in university classrooms, and at the professional development seminars I facilitate. (I have made it a practice to provide teachers with a copy of her book).

We have developed an enduring friendship, and I learn from her every time we meet. Ava has regaled me with many tales ranging from light and whimsical memories of growing up in Novi Sad; desperate times looking for her father, grandmother, sister and mother after the war; leaving for Israel with her mother in 1949 and building a life there; her decision to begin again in Chicago over thirty years ago after falling in love a second time in her 50s. Now 92, Ava has decided to permanently return to Israel this fall to be with her family. I am relieved to know her voice will continue to inspire others through the availability of her testimony that is part of the USC Shoah Foundation archive.

Patrick Nolan is a Holocaust educator at Sandalwood High School/Florida and State College at Jacksonville, South Campus, Jacksonville, Florida.

I have been studying the history of the Holocaust for more than thirty years; in that time I am sure I have read hundreds of books, articles, journal entries, or other pieces of writing related to the Holocaust. Several stand out and have served as inspiration for the lessons I teach. One in particular has  always haunted me, and I use excerpts from this text to teach about the horrors of the Holocaust in general—particularly in the ghettos—and the impact the Holocaust had on a single human being to whom my students can relate.

always haunted me, and I use excerpts from this text to teach about the horrors of the Holocaust in general—particularly in the ghettos—and the impact the Holocaust had on a single human being to whom my students can relate.

The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak, while certainly not as well known or widely-read as Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl, is a stunning exploration into how human depravity impacted the lives of so many young, vibrant, innocent people in places like Lodz, Warsaw, Lublin, and other ghettos. When the attack on Poland commenced on September 1, 1939, the young Dawid Sierakowiak writes about it with what can only be described as a sense of exhilaration. He seems to mock the older women who scream and cry at the sound of bombs exploding and airplanes flying overhead, largely because to him this is an exciting moment in his life—he has no memory of war, and therefore, like other teenagers, there is no sense of the reality of what is happening to his country and to his fellow Poles. It doesn’t take long in the narrative for Sierakowiak’s demeanor to change, and when his mother is taken away—to the east for resettlement?—he cannot muster tears to cry for her and for his own loss. Sierakowiak’s diary ends abruptly, as did the lives of millions of people during the Holocaust. We have Sierakowiak’s words as testimony to what he endured, but we do not have Sierakowiak himself to embrace and to reassure. Such a young life, snuffed out in its prime, should serve as a reminder of the tenuous connection all humanity has to the whims of those who would conquer and control us. My students are moved by Sierakowiak’s story, as am I. I will continue to tell his story in his own words so that my students, who are his age now, will better understand and appreciate both what they have and what was taken away from so many others.

English

English