This multipart resource is intended to help teachers support students’ understanding of genocide in the context of their Holocaust education.

Why is it valuable to teach about genocide in the context of learning about the Holocaust?

• The Holocaust is often considered to have given rise to our conceptualization of the term "genocide," which was coined during the Second World War, in large measure as a response to the crimes of the Nazis and their collaborators. Therefore the Holocaust can be an effective starting point and the foundation for studying genocide.

• Students can sharpen their understanding not only of similarities between events but also of key differences. In so doing, it may be an opportunity to better understand the particular historical significance of the Holocaust, and how study of the Holocaust may contribute to our understanding of other genocidal events.

• Students can identify common patterns and processes in the development of genocidal situations. Through the understanding of a genocidal process and by identifying stages and warning signs in this process, a contribution can hopefully be made to prevent future genocides.

• Students can appreciate the significance of the Holocaust in the development of international law, establishment of tribunals, and attempts by the international community to respond to genocide in the modern world.

• Students can gain awareness of the potential danger for other genocides and crimes against humanity that existed prior to the Holocaust and continue to the present day. This may strengthen an awareness of their own roles and responsibilities in the global community.

[1] "Education Working Group Paper on the Holocaust and Other Genocides" (2010)

Additional Considerations

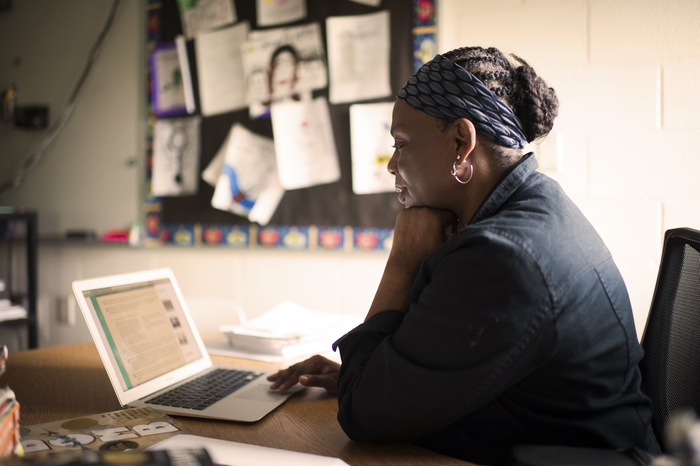

• A central tenant of the Echoes & Reflections methodology is the use of primary source materials, which we have provided in the form of visual history testimonies. Learn more about the Echoes & Reflections pedagogy here.

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

• cultural resistance: acts of opposition that are usually related to cultural traditions and the preservation of human dignity, intended to undermine an oppressor and inspire hope within the ranks of the resistors.

• spiritual resistance: acts of resistance aimed at preserving human dignity in dehumanizing conditions

The framework below is based on the 10 Stages of Genocide, as defined by Gregory H. Stanton, originally presented as a briefing paper, “The Eight Stages of Genocide,” at the US State Department in 1996. “Discrimination” and “Persecution” were added later to the model. Dr. Stanton is the President of Genocide Watch, and Research Professor in Genocide Studies and Prevention at George Mason University in Virginia. According to Stanton, “Genocide is a process that develops in ten stages that are predictable but not inexorable. At each stage, preventive measures can stop it. The process is not linear. Stages may occur simultaneously. Logically, later stages must be preceded by earlier stages. But all stages continue to operate throughout the process.”[1] There is a concise definition of each stage for ease in communication with students, followed by Stanton’s full definition, which also includes a suggested preventive measure. Teaching about genocide, just like teaching about the Holocaust specifically, provides an opportunity to engage students in deep reflection about choices made by individuals, governments, leaders, and larger societies at different points in time. Considering preventative measures is an important element to help students engage with the material.

To support this understanding, for each stage below, there are 2-3 testimonies from different genocides, including the Holocaust, to illustrate each stage. To help frame these testimonies, brief historical summary of genocide in Armenia, Cambodia, and Rwanda are included on the right here. For links to additional materials, visit the Additional Resources section. Teaching about genocide can be complicated, and requires planning and sensitivity. Just like teaching about the Holocaust, providing historical context is a critical element. In reviewing these summaries, and other supporting information, affirm students’ understanding using some or all of the following questions:

- When and where did the events occur?

- Who were the victims?

- Who were the perpetrators?

- How was mass murder carried out?

- How did the international community respond?

- What happened in the aftermath?

In reviewing each stage and viewing the accompanying testimonies, support students’ learning using some or all of the questions below. You may also use the Graphic Organizer, located to the right:

- How does the testimony best illustrate this stage?

- Often various stages happen simultaneously. Is there more than one stage represented in this particular testimony?

- Watch the testimony a second time. Were there any words or phrases that stood out?

- What values or points of view are represented or left out of this testimony?

- In what ways did the testimony illuminate specific aspects of this time period?

It is important that students are guided to consider the power and opportunity that individuals have to make a difference in the face of hatred and violence. This is one way to bring students “safely in and safely out” of their study of the Holocaust, genocide, and mass violence. Consider the following discussion points to support them in their learning and understanding:

- What do you think Dr. Stanton means when he writes that we “must not confuse any stage with a status”? Why is this an important distinction?

- What is the value to learning about the stages of genocide? How does this help in prevention, both in impacting individual behaviors as well as societal and governmental actions?

- Do you agree with Dr. Stanton that “Ultimately the best antidote to genocide is popular education and the development of social and cultural tolerance for diversity?” Why or why not?

As Polish Resistance fighter Jan Karski explains in his testimony (featured in this unit), “Great crimes start with little things. You don’t like your neighbor. You don’t like him because he’s black or yellow or café con leche or whatever it is. Avoid this. Try to cooperate. Don’t make distinctions.” As educators, teaching about genocide is one step to getting students to this ideal. [1] http://www.genocidewatch.org/genocide/tenstagesofgenocide.html

| 1 | Classification |

In this stage, people are divided into “us versus them.” Stanton’s Full Definition: All cultures have categories to distinguish people into “us and them” by ethnicity, race, religion, or nationality: German and Jew, Hutu and Tutsi. Bipolar societies that lack mixed categories, such as Rwanda and Burundi, are the most likely to have genocide. The main preventive measure at this early stage is to develop universalistic institutions that transcend ethnic or racial divisions, that actively promote tolerance and understanding, and that promote classifications that transcend the divisions. The Catholic Church could have played this role in Rwanda, had it not been riven by the same ethnic cleavages as Rwandan society. Promotion of a common language in countries like Tanzania has also promoted transcendent national identity. This search for common ground is vital to early prevention of genocide. | |

| 2 | Symbolization |

In this stage, there is a name or symbol for the classification, such as the yellow star as a Nazi symbol for Jewish people. When combined with hatred, symbols may be forced upon unwilling members of groups that are marginalized and made into pariahs. Stanton’s Full Definition: We give names or other symbols to the classifications. We name people “Jews” or “Gypsies,” or distinguish them by colors or dress; and apply the symbols to members of groups. Classification and symbolization are universally human and do not necessarily result in genocide unless they lead to dehumanization. When combined with hatred, symbols may be forced upon unwilling members of pariah groups: the yellow star for Jews under Nazi rule, the blue scarf for people from the Eastern Zone in Khmer Rouge Cambodia. To combat symbolization, hate symbols can be legally forbidden (swastikas) as can hate speech. Group markings like gang clothing or tribal scarring can be outlawed, as well. The problem is that legal limitations will fail if unsupported by popular cultural enforcement. Though Hutu and Tutsi were forbidden words in Burundi until the 1980’s, code words replaced them. If widely supported, however, denial of symbolization can be powerful, as it was in Bulgaria, where the government refused to supply enough yellow badges and at least eighty percent of Jews did not wear them, depriving the yellow star of its significance as a Nazi symbol for Jews. | |

| 3 | Discrimination |

In this stage, a dominant group uses law, custom, and political power to deny the rights of other groups. The powerless group may not be accorded full civil rights or even citizenship. Stanton’s Full Definition: A dominant group uses law, custom, and political power to deny the rights of other groups. The powerless group may not be accorded full civil rights or even citizenship. Examples include the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 in Nazi Germany, which stripped Jews of their German citizenship, and prohibited their employment by the government and by universities. Denial of citizenship to the Rohingya Muslim minority in Burma is another example. Prevention against discrimination means full political empowerment and citizenship rights for all groups in a society. Discrimination on the basis of nationality, ethnicity, race or religion should be outlawed. Individuals should have the right to sue the state, corporations, and other individuals if their rights are violated. | |

| 4 | Dehumanization |

In this stage, one group denies the humanity of the other group. Members of it are equated with animals, vermin, insects, or diseases. At this stage, hate propaganda in print and other media is used to vilify the victim group. Stanton’s Full Definition: One group denies the humanity of the other group. Members of it are equated with animals, vermin, insects or diseases. Dehumanization overcomes the normal human revulsion against murder. At this stage, hate propaganda in print and on the radio is used to vilify the victim group. In combating this dehumanization, incitement to genocide should not be confused with protected speech. Genocidal societies lack constitutional protection for countervailing speech, and should be treated differently than democracies. Local and international leaders should condemn the use of hate speech and make it culturally unacceptable. Leaders who incite genocide should be banned from international travel and have their foreign finances frozen. Hate radio stations should be shut down, and hate propaganda banned. Hate crimes and atrocities should be promptly punished. | |

| 5 | Organization |

In this stage, genocide is organized, often by the state. Sometimes organization is informal or decentralized. Special army units or militias are often trained and armed. Plans are made for genocidal killings. Stanton’s Full Definition: Genocide is always organized, usually by the state, often using militias to provide deniability of state responsibility (e.g., the Janjaweed in Darfur.) Sometimes organization is informal (e.g., Hindu mobs led by local RSS militants) or decentralized (e.g., terrorist groups.) Special army units or militias are often trained and armed. Plans are made for genocidal killings. To combat this stage, membership in these militias should be outlawed. Their leaders should be denied visas for foreign travel. The United Nations should impose arms embargoes on governments and citizens of countries involved in genocidal massacres, and create commissions to investigate violations, as was done in post-genocide Rwanda. | |

| 6 | Polarization |

In this stage, extremists drive the groups apart with polarizing propaganda and laws that may forbid intermarriage or social interaction. Extremist terrorism targets moderates, intimidating and silencing the center. Stanton’s Full Definition: Extremists drive the groups apart. Hate groups broadcast polarizing propaganda. Laws may forbid intermarriage or social interaction. Extremist terrorism targets moderates, intimidating and silencing the center. Moderates from the perpetrators’ own group are most able to stop genocide, so are the first to be arrested and killed. Prevention may mean security protection for moderate leaders or assistance to human rights groups. Assets of extremists may be seized, and visas for international travel denied to them. Coups d’état by extremists should be opposed by international sanctions. | |

| 7 | Preparation |

In this stage, national or perpetrator group leaders indoctrinate the populace with fear of the victim group and plan the extermination of that population. They often use euphemisms to cloak their intentions, such as referring to their goals as “ethnic cleansing,” “purification,” or “counter-terrorism.” They build armies, buy weapons, and train their troops and militias. Stanton’s Full Definition: National or perpetrator group leaders plan the “Final Solution” to the Jewish, Armenian, Tutsi or other targeted group “question.” They often use euphemisms to cloak their intentions, such as referring to their goals as “ethnic cleansing,” “purification,” or “counter-terrorism.” They build armies, buy weapons and train their troops and militias. They indoctrinate the populace with fear of the victim group. Leaders often claim that “if we don’t kill them, they will kill us.” Prevention of preparation may include arms embargos and commissions to enforce them. It should include prosecution of incitement and conspiracy to commit genocide, both crimes under Article 3 of the Genocide Convention. | |

| 8 | Persecution |

In this stage, victims are identified and death lists are drawn up. Genocidal massacres begin. Stanton’s Full Definition: Victims are identified and separated out because of their ethnic or religious identity. Death lists are drawn up. In state-sponsored genocide, members of victim groups may be forced to wear identifying symbols. Their property is often expropriated. Sometimes they are even segregated into ghettoes, deported into concentration camps, or confined to a famine-struck region and starved. Genocidal massacres begin. They are acts of genocide because they intentionally destroy part of a group. At this stage, a Genocide Emergency must be declared. If the political will of the great powers, regional alliances, or the United Nations Security Council can be mobilized, armed international intervention should be prepared, or heavy assistance provided to the victim group to prepare for its self-defense. Humanitarian assistance should be organized by the U.N. and private relief groups for the inevitable tide of refugees to come. | |

| 9 | Extermination |

In this stage, killing quickly becomes the mass killing legally called “genocide.” It is “extermination” to the killers because they do not believe their victims to be fully human. Stanton’s Full Definition: Extermination begins, and quickly becomes the mass killing legally called “genocide.” It is “extermination” to the killers because they do not believe their victims to be fully human. When it is sponsored by the state, the armed forces often work with militias to do the killing. Sometimes the genocide results in revenge killings by groups against each other, creating the downward whirlpool-like cycle of bilateral genocide (as in Burundi). At this stage, only rapid and overwhelming armed intervention can stop genocide. Real safe areas or refugee escape corridors should be established with heavily armed international protection. (An unsafe “safe” area is worse than none at all.) The United Nations Standing High Readiness Brigade, EU Rapid Response Force, or regional forces — should be authorized to act by the United Nations Security Council if the genocide is small. For larger interventions, a multilateral force authorized by the United Nations should intervene. If the United Nations is paralyzed, regional alliances must act. It is time to recognize that the international responsibility to protect transcends the narrow interests of individual nation states. If strong nations will not provide troops to intervene directly, they should provide the airlift, equipment, and financial means necessary for regional states to intervene. | |

| 10 | Denial |

The final stage is denial. It lasts throughout and always follows a genocide. The perpetrators of genocide deny that they committed any crimes, and try to cover up the evidence. Stanton’s Full Definition: Denial is the final stage that lasts throughout and always follows a genocide. It is among the surest indicators of further genocidal massacres. The perpetrators of genocide dig up the mass graves, burn the bodies, try to cover up the evidence, and intimidate the witnesses. They deny that they committed any crimes, and often blame what happened on the victims. They block investigations of the crimes, and continue to govern until driven from power by force, when they flee into exile. There they remain with impunity, like Pol Pot or Idi Amin, unless they are captured and a tribunal is established to try them. The response to denial is punishment by an international tribunal or national courts. There the evidence can be heard, and the perpetrators punished. Tribunals like the Yugoslav or Rwanda Tribunals, or an international tribunal to try the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, or an International Criminal Court may not deter the worst genocidal killers. But with the political will to arrest and prosecute them, some may be brought to justice. The response to denial is punishment by an international tribunal or national courts. Prevention begins with education and awareness. | |

Genocide Prevention /Activism

- Auschwitz Institute for Peace and Reconciliation (AIPR)

- Early Warning Project

- Genocide Watch

- International Crisis Group

- NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies

- The Ten Stages of Genocide

- UNESCO Education about the Holocaust and preventing genocide: a policy guide

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide

- World Without Genocide

Genocide Studies

- Aegis Trust

- “Confronting Genocide: Never Again?” Brown University, The Choices Program (June 2016)

- Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies (MIGS)

- USC Shoah Foundation’s Center for Advanced Genocide Research

- Yale University, the Genocide Studies Program

Genocide Case Studies Armenia

- Testimony-based educational resources to teach about Armenian genocide

- Genocide Education Project

- New York Times “Teaching the Armenian Genocide”

Cambodia

- Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-CAM)

- Genocide Watch “Teacher’s Guidebook: A History of Democratic Kampuchea (1975-1979)”

Guatemala

- Holocaust Museum Houston “Genocide in Guatemala”

- Pledge Peace Union “Talking About Genocide—Guatemala”

Rwanda

These programs are designed to enhance teachers’ knowledge, capacity, and confidence to teach about the Holocaust. Educators are introduced to pedagogical principles and explore classroom lessons, visual history testimonies and other resources that examine aspects of the history and its continued relevance today. Programs can provide broad historical overview grounded in effective instructional strategies or focus on specific themes aligned with Echoes & Reflections Units below:

|

|

Grounded in relevant aspects of Holocaust history, the following programs connect learning to contemporary issues and concerns of today, introducing Echoes & Reflections and supplementary classroom resources to examine these topics with students.

Antisemitism: Understanding and Countering this Hatred Today

It is critical for young people to understand the dangers of antisemitism today and the threat that it poses to both Jewish and non-Jewish populations. This program helps teachers to educate about antisemitism, examining its complexities from historic and contemporary perspectives. Educators gain strategies to help students respond to and counter antisemitism and forms of hate.

Advancing Civic Participation through Holocaust Education

Studying the Holocaust imparts essential lessons of civic values, including justice, tolerance, and the importance of democratic liberties. By using Echoes pedagogical approach and examining the rise of the Nazi party, participants bridge memory into action and inspire students to participate in political processes in their community.

Analyzing Propaganda and Teaching Media Literacy: The Holocaust as a Case Study

Participants explore the events of the Holocaust through the lens of media, by examining propaganda deployed by the Nazis to discriminate against Jews and other minorities. Educators gain tools to facilitate classroom discussions and support students to analyze media in today’s world.

How We Remember: The Legacy of the Holocaust Today

How did the world respond when the reality of the Holocaust came to light? During this program, educators examine the pursuit of justice at Nuremberg, the effect the trials had on how we understand the Holocaust, how survivors coped with the trauma to build new lives in the aftermath, and how we remember and memorialize the Holocaust today.

Teaching About Genocide

Using effective pedagogy, educators examine four specific genocides, including the Holocaust, to explore common themes. Participants learn about the identities of victims of genocide before the catastrophe as well as how a society was incited and organized to attack them. Educators also look at the effects of genocide on society as well as how memorialization and memory affect their legacies.

It Starts with Words: Teaching the Escalation of Hate

The Holocaust arose out of antisemitic hatred fueled in part by the power of words. Participants examine the escalation of words to violence, which in turn, became genocide in order to consider where such a progression might have been interrupted. Educators also gain tools to apply these lessons to modern day issues faced by students.

An important element of the Echoes & Reflections approach is the inclusion of multidisciplinary methods to ensure students learn the human story behind the Holocaust. These programs, of particular interest to ELA and Humanities educators, highlight various sources – from literature to photographs – to engage learners.

Creating Context for Teaching the Holocaust through Literature

In this program, educators learn instructional strategies for teaching the Holocaust through literary selections. This could include a focus on Elie Wiesel’s Night, The Diary of Anne Frank, and/or Maus, or can be adapted to include other works of literature for the classroom by request. In all cases, participants explore Echoes & Reflections resources to provide essential, larger historical framework of the Holocaust to integrate into their classroom instruction. This approach will help build historical understanding, create empathy, and provoke compassion with students.

Women in the Holocaust

The Nazi regime subjected women to violence that was unique to the gender of the victims, and examining the Holocaust through this lens creates a more nuanced understanding and insight into the use of gender as a weapon. This program explores the unique experiences of women as they focused on daily survival, refused to be dehumanized, and were often at the heart of resistance, whether spiritual, cultural, or armed. This program can be tailored to focus on women as fierce resistors, as survivors of the Nazi death machine, or as rescuers awarded the title “Righteous Among the Nations.”

Teaching the Holocaust Using the Humanities: Integrating Photographs, Literature, Art, and Poetry to tell the Human Story

Educators learn strategies to integrate multiple primary sources into Holocaust instruction with a focus on the human experience. Programs can examine a range of sources or be narrowed to focus on a specific type of source including specific programs on The Auschwitz Album, Photography as Resistance, etc.

Examining the Holocaust and World War II: Teaching with The U.S. and the Holocaust, a film by Ken Burns, Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein

What did the average American know about the Holocaust as it was occurring and what was the response? This program uses content from The U.S. and the Holocaust, a film by Ken Burns, Lynn Novick & Sarah Botstein, to examine how the American people responded to one of the greatest humanitarian disasters of the twentieth century, and how this catastrophe challenged our identity as a nation and the very ideals of our democracy.

Echoes & Reflections is proud to partner with USC Shoah Foundation, Hold On To Your Music Foundation, and Discovery Education to bring the Willesden READS Program to students and teachers in select cities across the United States.

Discover teaching resources to support the Willesden READS and more at The Willesden Project.

THE STORYThe Children of Willesden Lane–editions now available for readers across grade levels-is the best-selling story about the power of music and how one teenage refugee, Lisa Jura, Mona’s mother, held onto her dreams, survived the Holocaust and inspired a generation of her contemporaries. Today's worldwide humanitarian crises and the importance of standing up against bigotry and hatred are reflected in the continued, growing relevance of this story.

THE PROGRAMThe centerpiece event of the Willesden READS Program is a 50-minute one of a kind livestreamed event including a theatrical performance and concert based on the The Children of Willesden Lane story. More than one million students across the world have experienced the Willesden READS program. During this special remote event, students will have opportunities to interact with the book's author, performer and virtuoso concert pianist Mona Golabek, who offers uplifting messages of resilience and hope for students at a time when they most need it.

In advance of the livestream event, educators are invited to participate in professional development, provided by Echoes & Reflections, to deepen understanding of the historical context of The Children of Willesden Lane books and to learn to incorporate companion resources found in IWitness, USC Shoah Foundation's educational website, into their teaching.

Watch this brief video to learn more about the Willesden READS Program.

Currently in the United States, 12 states mandate Holocaust education, 5 have permissive statutes (legislation that is not a requirement), 14 support a Holocaust education commission or taskforce, 4 have legislation pending, and 22 have no legislation regarding Holocaust education (note: some states may fall into multiple categories).

Tap the button below to review state legislation. Visit this page on desktop to explore an interactive map.

For questions, and for more information on our offerings and/or on Holocaust education in your state, please contact us at info@echoesandreflections.org.