As we know, a Tennessee school board voted recently to ban use of the graphic novel Maus in its 8th grade classrooms. Sadly, the losers in this fight are – as always – the students, for whom a great work of literature is erased. Interestingly, the winner by a landslide is Maus – sales of which have skyrocketed on Amazon since the ban, and free copies of which are set to be provided to students. All this proves that banning books can be quite the boomerang.

Books can open new worlds. They can spark imagination. They can transport readers to different places, show them different perspectives, and introduce them to different ideas. But not when they are banned.

Those of us who teach the Holocaust know the value of books. Readers can literally explore the unknown and transcend physical boundaries: this is why so many ghettos during the Holocaust had libraries and so many imprisoned and persecuted people – especially children – read books. In December, 1942 in Vilna, even after tens of thousands of Jews had been murdered and death was all around, the ghetto library held a ceremony marking the loan of the 100,000th book. In the Warsaw ghetto, children continued to borrow books during the Great Deportation in the summer of 1942 during which almost 300,000 Jews were murdered. Often the books they borrowed were never returned; they were packed into the bundles the children took with them to the Treblinka death camp. “The ghetto child, robbed of the world—the river, the green trees, freedom of movement—could win all this back through the magic of the printed word.”[1]

For these reasons, books hold a special reverence for us.

The Supreme Court has agreed, holding in Board of Education v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982) that the First Amendment limits the power of officials to remove books[2] from school libraries.[3]

It turns out that book banning goes back at least as far as Plato in 360 B.C.[4] For as long as books have been written, there have been those who have pushed to ban them. Even classic literature such as Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and classic authors such as Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, have been challenged. In 2001 student access to the “Harry Potter” book series was challenged (because of references to witchcraft and the occult). Those who support book bans generally fear that the books in question present ideas, raise issues or provoke critical inquiry that they find inappropriate. Yet, isn’t that the function of education? Don’t we want to support freedom of thought, of expression, of speech? Don’t we want students to explore new issues and to think for themselves? Often, challenged books are entry points into difficult subjects that need to be discussed.

This is why it’s so sad for the students of McMinn County to lose a book like Maus over eight curse words and one ostensibly objectionable picture.

Maus is a brave and unflinching work. It is the author’s father’s first-person, eyewitness account of the Holocaust. As such, it functions as Holocaust history through a personal story (something Echoes & Reflections firmly advocates). But it is also the author, Art Spiegelman’s, account of his relationship with his aging survivor father, and how he experienced writing about the experience of being a survivor’s son. On this level it depicts the process of transmitting and recording memory and trauma, and how the present is continuously shaped by the past.

Maus is both an authentic Holocaust story and a story of the “second generation” – its honesty without sentimentality is what makes it so memorable and powerful. In its pages are discrimination, persecution and hate, as well as resilience, resistance and perseverance: all very human, very real, very gritty. Nothing is sugar-coated; this is part of its appeal.

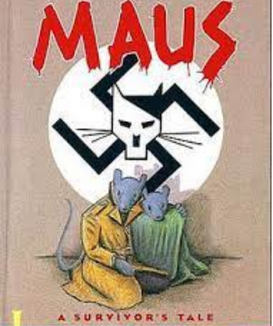

What distinguishes Maus still more is that it is written as a graphic novel, where mice are used to represent Jews, Germans are represented by cats, and other ethnic groups are represented by other animals. It is an allegory: the Germans viewed Jews not as people, but as vermin, which is why the book begins with a quote by Adolf Hitler, “The Jews are undoubtedly a race, but they are not human.” Spiegelman has said that his anthropomorphic characters call attention to the absurdity of dividing people up into different animal groups, and take Hitler’s rhetoric to turn the notion of the subhuman back on itself by letting the mice “stand on their hind legs and insist on their humanity.” Using animal characters allowed Spiegelman to say otherwise unsayable things and show events too disturbing to show.

For all of these reasons, Maus won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992, and is read today in many high schools as well as in college courses. It brings new insights to the study of the Holocaust. And for all of these reasons, the ban in Tennessee has boomeranged – the school board may believe it is protecting the county’s students from eight curse words and an objectionable picture, but the students will be deprived of these insights and of a great work of literature.

To learn how to teach with Maus, join Echoes & Reflections webinar “Bringing Maus to the Classroom” on 2/23 at 3 PM ET. Register here.

About the author: Sheryl Ochayon is the Director of Echoes & Reflections for Yad Vashem.

[1] Rachel Auerbach, “The Librarians”, PaknTreger, Summer 2017, https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/language-literature-culture/pakn-treger/2017-pakn-treger-translation-issue/librarians.

[2] The list of books at issue included such classics as The Fixer, by Bernard Malamud; Slaughterhouse Five, by Kurt Vonnegut Jr.; and Black Boy, by Richard Wright, called by the Board of Ed, “anti-American…and just plain filthy.”

[3] The opinion’s scope was narrow because the case did not involve textbooks or required reading, but the Court sang the praises of books, libraries and broadening students’ worlds through reading.

[4] For an interesting summary of censorship of books and ideas through the centuries, see Claire Mullally and Andrew Gargano, “Banned Books”, Freedom Forum Institute, 2017, https://www.freedomforuminstitute.org/first-amendment-center/topics/freedom-of-speech-2/libraries-first-amendment-overview/banned-books/.

English

English