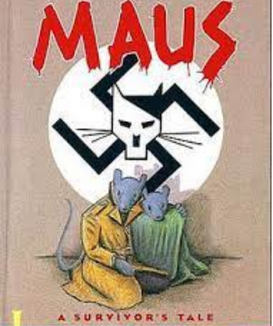

A swastika emblazoned on a wall. A cruel and insensitive joke. A comment seeping with antisemitic tropes of Jews having too much power or controlling the media. A shallow and inappropriate comparison of medical guidelines to the Holocaust. These are just a few of the countless antisemitic acts we see every day from our political leaders, news pundits, community members and, unfortunately, even students. But why has there been such a proliferation of comparisons and references to the Holocaust and Nazism recently? And perhaps more importantly, why and how should we address these issues in our classroom, especially when it is happening in our own schools and communities?

To prepare and guide our dialogue with our students, we must recognize, understand, and convey the power of symbols and symbolic language. As we have seen time and time again, both historically and in our present day, hate does not end with odious language and imagery. It has the real potential to cause increased harm by influencing more destructive acts–attacks on safe and sacred places: schools, places of worship, as witnessed by the attack in Colleyville, TX earlier this year, or cemeteries, just to name a few. It is clear these symbols of hate are influential, pernicious, and harm our entire communities, not just those who are targeted by their bigotry. These are spaces that help create and develop our identities and thus an attack on them is a clear, direct, and simple message of “you don’t belong here.” They are unsettling, foundation-shaking, and evoke fear and uncertainty on both our present lives and our hopes for the future.

Discussing dangers of the appropriation of Holocaust Imagery and Jewish Trauma with Students

Along with the obvious symbols of hatred, poor analogies and inappropriate comparisons to the Holocaust and Nazism can do just as much damage, but again, why are they so ubiquitous? Adolf Hitler, Nazism and the Holocaust are universally known in our society. Yes, studies have shown that many don’t know a lot of the specific facts and figures about this era, but a majority do believe the Holocaust was the most evil event in human history, perpetrated by Hitler and the Nazis. When trying to describe something or someone as evil, it is a cheap, shallow, but sadly an effective tool to brand it as Nazism or as terrible as the Holocaust.

Further, antisemitism is latent but ever-present in our society, and its hatred is rising and becoming increasingly overt. Because of this widespread bigotry, references that demean, delegitimize, and attack Jews and Judaism will continue to be effective until antisemitism is rooted out of our culture, our country, and our world. The politicians, world leaders, and adults who make these statements know what they are doing. It isn’t an accident. In an age of instant news and social media, there is an astute awareness that any inflammatory post or tweet will receive increased exposure. When this occurs, we should deconstruct this damaging rhetoric to help students understand the motivations and effects of these appalling statements. Using age-appropriate and constructive strategies to engage students, we can help them explore these incidents and understand the harm caused.

How do we address these issues when they happen in the classroom?

When confronted with an antisemitic comment or verbal attack, or presence of a symbol, be firm, direct, and give no leniency. This type of behavior is threatening, hateful, and completely unacceptable. The student(s) in question may backtrack their comments or actions and frame them as a joke or not important. Regardless, it is vital to convey to the student(s) that this is a serious matter and then invite them and all students to learn why.

After this point, we want to engage with our students to become critical thinkers, who examine images and statements with an analytical lens, seek truth and understanding of similar and opposing views, and ultimately be able to evaluate these actions in a rational manner. Echoes & Reflections’ pedagogy and approach centers student inquiry, utilizes tools such as graphic organizers and our Learn and Confirm Chart will help students navigate their way through difficult history.

For additional guidance on how to comprehensively address incidents of bias and hate in schools, including specific examples of antisemitic behavior, view ADL Education’s resource on this topic.

As we teach about the Holocaust, we obviously want our students to gain knowledge and learn the content, but we must not lose sight of the true purpose of education: To develop young people’s characters and thinking processes, and ultimately make them engaged global citizens who will improve the world in which we live in today. Thankfully, we know that Holocaust education is a powerful tool to achieve these goals and it has been shown to foster social responsibility, civic efficacy, and a greater willingness to challenge intolerant behavior in others.

And while we are seeing more and more hate-motivated incidents — which should always be reported to the proper authorities—we know that educators can play a critical role in intervention, education, and ideally prevention of the escalation of antisemitism and hatred among students. This is meaningful and transformative, yet challenging work. Echoes & Reflections is here to support you with our resources, professional development, and our team of experts.

About the author: Jesse Tannetta is a former high school teacher who is now the Program Manager for Echoes & Reflections. He holds a master’s degree in Holocaust and Genocide Studies and is a current Ph.D. student beginning his dissertation on female concentration camp guard Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan.

English

English