CURRENT EVENTS

LITERATURE

On the occasion of Anne Frank's 90th birthday, Anne Frank House Executive Director, Ronald Leopold, reflects on the relationship between the Holocaust and today: whether democratic societies, which were rebuilt with so much care in the shadow of the Holocaust, are in danger and how despite this fear, Anne Frank’s words can guide our youth to a brighter future. This piece was specially adapted for Echoes & Reflections from his keynote speech for the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center on June 5th, 2019.

On the occasion of Anne Frank’s 90th birthday, we recall that the remembrance of the Holocaust is connected to the present and the future.

Anne’s fifteenth birthday would also be her last, because not much later, fate intervenes. On August 4th, 1944, a raid takes place in the building at 263 Prinsengracht, in which all eight people in hiding and the two male helpers are arrested. The people in hiding are deported via the Westerbork transit camp in the East of the Netherlands to Auschwitz and from there to various other concentration camps. Of the eight, only Anne's father Otto Frank ultimately survives the war. The others perish under inhumane circumstances. Anne and her sister Margot succumb to typhus in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in mid-February 1945, two months before the camp is liberated.

But the meaning of the Anne Frank House goes further than the tragedy in which it is rooted. The House also forms a mirror in which we can see ourselves, not to admire our beauty like in a fairytale: Not “mirror, mirror, on the wall, who’s the fairest of them all?", but to be confronted with who we are, what we as human beings are capable of, what the values are that make us human. The fate of Anne and Margot Frank was the work of human hands. It was not the result of a natural disaster, not the work of creatures from another planet, not even the work of one particular type of person. Visitors to the Anne Frank House are invited to reflect on this, and challenged to ask themselves questions, often uncomfortable questions concerning our moral compass. Questions about the choices we make and the consequences they have for ourselves and for others, about the need to protect ourselves against ourselves.

Otto Frank remarked, shortly before the Anne Frank House opened in 1960, that “we should stop teaching history lessons and should start teaching lessons from history.” I don’t assert that we should stop teaching history lessons, but his intrinsic message was clear: history lessons are of little use if they don’t also serve as a mirror for our own actions.

What is the relevance of the Holocaust in the 21st century for generations whose grandparents and great-grandparents were born after WWII? Aren’t the circumstances and events of the past too distant from us? Can they still have a guiding significance in 2019? Or do we soon lose ourselves in slogans, in banal comparisons, in platitudes that sound good but can no longer serve as a moral compass.

History gives us food for thought, not so much because it repeats itself, but because it offers a view of what lies behind human thinking and actions. What motivated people to think and act the way they did? What considerations did they weigh, how do they explain their own time and how do we perceive it in retrospect?

Anyone who has thought about WWII and the Shoah inevitably comes up with the question of how things could have gone so far; at what moment might history have taken a different turn. Historians have already written libraries full about this and undoubtedly there will be much more written. But in 2019 that question also raises an urgent contemporary dilemma related to democratic vigilance: what do we see and hear around us, how do we “read” our own time, how do we interpret the risks? Is our open, democratic society and the rule of law, which we rebuilt with so much care in the shadow of the Holocaust, in danger? Has the world lost its way and are we en route to new tragedies?

Surely it will not happen to us again in a relatively short span of time that we miss the moment to turn the tide of history? That we let the “window to act” pass us by, while the warning lights of the past flash brighter and brighter? Are we going to make the same mistake twice?

“I hope you will be a great source of comfort and support,” Anne Frank wrote in the first sentence of her diary, still unaware of how important this support would prove to be in the more than two years that followed. We can only speculate about her thoughts during the last months of her young life in Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen. Was she able to hold on to her dreams and ideals in a situation of increasing hopelessness? Did she still believe that “. . . people are truly good at heart”, as she had written in her diary a short time before the arrest? Did she gaze at the sky, like she had earlier through the attic window of the hiding place, and think everything is going to turn out alright?

The dreams expressed by Anne Frank implore us to think about who we are and who we want to be, about the world in which we now live and the one we want to live in, about the things that make us human. Her life story serves as a warning and as a source of inspiration, as a guide to achieving a better world, a better future. It is important to realize that Anne Frank's short life began in 1929 in a free and democratic Germany and ended a mere fifteen years later in a world of total barbarism. This malevolence did not begin with the outbreak of WWII, but in the years 1932-1933 with the rapid demise of German democracy and the Nazi takeover of power.

I don't believe we are facing that same inconceivable question at this moment. But I do believe there is every reason to more vigorously defend our open, democratic society and the rule of law. The question I ask is whether we maintain enough of a connection with this contemporary, everyday context. Wouldn’t it be better if we took that context as the starting point for a Shoah-related educational experience instead of a history lesson? Speaking in management terms, shouldn’t we have remembering the Shoah “pulling” from the present instead of “pushing” from the past?

Youth help us fulfil our missions and accordingly build the world of their dreams. They offer us new perspectives, which are accompanied by new connotations. Let us therefore consider how we can actively engage young people, listen to them and welcome them with open arms. It is my experience that there are many very talented and committed young people, sometimes incredibly young, from whom we can learn a lot.

Since the first publication of the Diary of Anne Frank in 1947, it has been read by millions of young people around the world. In the words she penned, they hear the voice of someone their own age, a peer. Her dreams are their dreams.

I want to take you back to April 11, 1944. It’s a lovely spring day in Amsterdam, with a clear blue sky, almost 70 degrees outside, a mild breeze is blowing. A long, bitter cold winter is finally giving way to the first warmth of the year. The trees are budding; it will not be long now before they’re in full bloom. It is a day full of yearning, yearning for everything that has been missing for so long: the warm rays of the sun on your skin, fresh air, the smell of nature awakening. Anne Frank is at her desk in the musty annex writing one of the longest and most moving entries in her diary.

A break-in downstairs in the building makes her once again realize that she’s in hiding, makes her think about being Jewish and what that means to her. She’s scared but determined to be brave and strong. She’s ready for death but wants to live, wants to make her mark on the world. She reflects on who she is and who she wants to be: a Jew; Dutch; a woman with inner strength, a goal, opinions, religion and love.

“If only I can be myself, I'll be satisfied.”

With these simple words Anne Frank reveals something very personal to us. On that beautiful spring day, she doesn’t share an identity claim with us, but the desire for space and the freedom to discover and develop herself. Her diary is the consequence of that search. She has been locked up in a small space with seven others for more than two years, continually discovering herself but always realizing that she is part of a group of people who are dependent on one another. She wants to make her voice heard, she has strong opinions, but is also vulnerable and prepared to change her point-of-view, even if this is easier said than done. Each time she asks herself questions and presents herself with dilemmas. And she realizes if she must get along with the seven other inhabitants of the Secret Annex, that she sometimes has to comply with their wishes.

The very last sentence of her diary speaks volumes: “. . . [I] keep on trying to find a way to become what I’d like to be and what I could be, if . . . if only there were no other people in the world.” But other people live there as well. “If only I can be myself” Just like in the diary, not as an identity claim, but as an individual desire and a democratic endeavor to ensure that everyone has the opportunity and freedom to discover and develop themselves, while keeping in mind that other people live in the world. Whoever reads Anne Frank’s diary cannot help but think about the dilemmas this presents, about what kind of attitudes and abilities are required of us. This isn’t going to give us the best of all possible worlds, but hopefully it will spare us the Hell that Anne Frank, Margot Frank, and millions of others were forced to endure. They were not only prohibited from being their true selves, but from being at all.

About the Author: Ronald Leopold has been the executive director of the Anne Frank House since 2011. Leopold held various posts at the Dutch General Pension Fund for Public Employees and was involved in the implementation of the legislation regarding war victims. Leopold lives in Amsterdam with his wife and daughter.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

TEACHING

Is it possible to teach respect for racial and religious differences?

This is a question I hear a lot from teachers who are committed to social justice but frustrated by mounting evidence of blunt and sometimes deadly prejudice. ADL recently confirmed that since 2016 antisemitism has dramatically increased in the U.S. and abroad. The Southern Poverty Law Center (SLPC) reports, “a surge of incidents involving racial slurs and symbols, bigotry and the harassment of minority children in the nation’s schools.”

It’s a fair question, and a rational one. Does classroom instruction on racial and religious tolerance make any difference at a time when intolerance is on the rise?

It does, and scholars have documented that studying the Holocaust and racial equality cultivates respect for diversity and fortifies democratic ideals. Teaching about the Holocaust is one of the most powerful ways to help young people understand the dangers of unchecked biases, and how, even in modern, democratic societies, these biases can escalate to catastrophic proportions.

In fact, the nation’s first program of anti-bias education was developed during World War II to “inoculate” American youth against Nazism. As one teacher insisted in 1941, “The most vital program of our country today and one, therefore, especially important to our schools is the promotion of the doctrine of tolerance as a means of knitting our nation into one closely integrated unit.” Scholars including the anthropologists Franz Boas, Ruth Benedict, and Margaret Mead developed K-12 curricula—including comic books and animated films—designed to teach students that Judaism was a religion, not a race, and that there was no such thing as racial superiority.

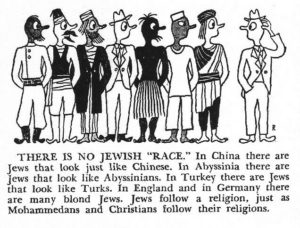

Figure 1 An image from The Races of Mankind, by anthropologists Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish, in 1944. Anthropologists during World War II believed that teaching the scientific definition of race would undermine Nazi racial doctrines and fortify American democracy.

Times of crisis, like World War II, force educators and politicians to recognize that unchecked bias is a direct threat to American democracy. That is why antiracist education became so popular during World War II, as I document in my book, Color in the Classroom: How American Schools Taught Race, 1900-1954.

It’s also why anti-bias education is such a hot topic today. Anti-bias education is designed to address prejudices including racial, religious, ethnic, gender, sexuality, social class, and immigration status. Teaching young people to identify and resist biased attitudes usually includes a study of historical events where small prejudices grew into acts of discrimination, which, in some cases, escalated into state-sponsored violence and genocide. The Pyramid of Hate found in Echoes & Reflections offers students a graphic representation of this danger.

As the Director of the Holocaust, Genocide, and Human Rights Education Project at Montclair State University (MSU), I have seen interest in our anti-bias programs surge since 2016. Our Holocaust education workshops fill up with a diverse group of people including not only K-12 teachers, but also school administrators and college students. Other human rights programs such as Native American environmental justice and support for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGTBQ) students are also popular. Educators are ready to teach lessons emphasizing respect for diversity and equality—what they need is more support.

This is where higher education has a vital role to play. American colleges and universities can support stronger and more robust anti-bias education in our K-12 schools. The question is, how?

First, universities can host professional development workshops such as Echoes & Reflections for K-12 educators and student teachers, including alumni. These workshops offer hands-on training in how to teach about the Holocaust—a topic that many K-12 teachers are nervous or unprepared to talk about. Participants gain access to online teaching materials including primary historical documents, photographs, interactive maps, and survivor testimony and are provided with models of how to incorporate these texts into effective lessons. Special thematic workshops on topics like antisemitism or immigration help teachers make direct connections between the Holocaust and current events. At MSU, we find that blended workshops with K-12 educators and student teachers create especially dynamic spaces. What is more, when a prominent university hosts a social justice education workshop for local teachers, it signifies to the broader public scholarly support for anti-bias education.

Second, scholars and university administrators can advocate for legislation requiring anti-bias education in public schools. New Jersey is a leader in this area. In 1994 state legislators mandated education on the Holocaust and genocide. Earlier this spring, New Jersey passed a law requiring instruction on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender social, political, and economic contributions. These laws provide critical support for anti-bias education in public schools, especially in communities where such lessons may be seen as controversial. In New Jersey, teachers can point to state law and continue the hard work of teaching children to understand and respect one another’s differences. The New Jersey Commission on Holocaust Education coordinates anti-bias education through a network of centers located the state’s public and private colleges and universities. Despite New Jersey’s success as a leader in anti-bias education, few other states have similar structures in place. If more states required and supported anti-bias education, it would expand training, resources, and support for K-12 teachers.

Figure 2 A Human Rights Education Intern at Montclair State University teaches about the Syrian refugee crisis to local middle school students.

Third, universities can mobilize our greatest resource to promote anti-bias education—our amazing students. MSU hosts a Human Rights Education Internship, where undergraduate students can apply to train as professional human rights educators. Interns select a specific human rights issue and spend a semester learning about human rights law, researching their selected topic, developing an effective lesson on it for a secondary school audience, and then teaching it in a local school. This spring we hosted a “Human Rights University for a Day” at Montclair High School, where interns taught lessons on Holocaust denial, the gender wage gap, juvenile incarceration, school segregation, religious tolerance, the Central American refugee crisis, the healthcare crisis in Venezuela, child labor, and colorism. The internship serves two purposes—first, it allows undergraduate students to train as human rights educators, skills they will carry with them into their future professions. Second, the internship sends undergraduate students as human rights education ambassadors into local public schools, where they not only teach about important subjects that are not necessarily part of the regular curriculum, but where they also model what it looks like to be an engaged, socially conscious college student. Put plainly, human rights education interns inspire youth to go to college! The results are inspiring for both our interns and the high school students they meet, and help our university forge new relationships with our local community.

Is it possible to teach respect for racial and religious differences in K-12 schools? The answer is yes, but our teachers need more help and American colleges and universities are uniquely positioned to provide it.

About the Author: Dr. Zoë Burkholder is an Associate Professor of Educational Foundations at Montclair State University, where she serves as Director of the Holocaust, Genocide, and Human Rights Education Project (On Facebook: @MSUHumanRights). She is the author of Color in the Classroom: How American Schools Taught Race, 1900-1954 (Oxford University Press, 2011). She may be contacted at burkholderz@montclair.edu

This site contains links to other sites. Echoes & Reflections is not responsible for the privacy practices or the content of such Web sites. This privacy statement applies solely to information collected by echoesandreflections.org.

We do not use this tool to collect or store your personal information, and it cannot be used to identify who you are. You can use the Google Analytics Opt-Out Browser Add-on to disable tracking by Google Analytics.

We currently do not use technology that responds to do-not-track signals from your browser.

Users may opt-out of receiving future mailings; see the choice/opt-out section below.

We use an outside shipping company to ship orders. These companies are contractually prohibited from retaining, sharing, storing or using personally identifiable information for any secondary purposes.

We may partner with third parties to provide specific services. When a user signs up for these services, we will share names, or other contact information that is necessary for the third party to provide these services.

These parties are contractually prohibited from using personally identifiable information except for the purpose of providing these services.

1. You can unsubscribe or change your e-mail preferences online by following the link at the bottom of any e-mail you receive from Echoes & Reflections via HubSpot.

2. You can notify us by email at info@echoesandreflections.org of your desire to be removed from our e-mail list or contributor mailing list.

English

English