CLASSROOM LESSONS

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

In a climate of increased antisemitism and other hate-related incidents, working to encourage empathy and empathic leadership certainly seems to me to be profoundly important in today’s world.

When I was five years old, my mother presented me with a pair of ice skates that she had worn as a child. She could hardly get the words out to tell me about this special gift and I can still envision her tearful face that day long ago. These were not ordinary ice skates. They were brown and old and didn’t look at all like the pretty white ice skates that my friend’s parents had bought them at the local store. This was no typical presentation of a childhood artifact to an offspring. These skates had been worn by my mother when she was growing up as a happy Jewish child in Vienna, Austria, before the Nazis took over in March of 1938. These skates were a physical testament to her life before her parents (my grandparents) were murdered in The Holocaust. My mother had taken these skates with her when at the tender age of thirteen, she was forced to leave her parents a few days after Kristallnacht. These skates had then been hidden under the ground for the three horrific war years that my mother had spent in hiding without her family and as a teenager in Holland. These skates were the embodiment of her survival and of her profound losses: of her childhood, home, country, family, and even her sense of self.

I knew that I didn’t have relatives, and that something horrible had happened to my mother. But this actual physical manifestation of her trauma shown to me when I was young left a profound impact on my life. It shaped who I am and started my own journey toward developing empathy toward others’ suffering. More importantly, directly hearing and seeing the terrible impact of trauma created a desire in me to want to work to develop empathy in others and try to create a better world. Throughout this work, I consciously utilized what I understood about my personal connections to my family’s Holocaust stories, to reach students and help them to care about others.

Research shows that when students learn to become more empathic, they improve their communication skills, lessen the likelihood of anti-social behavior, demonstrate higher academic achievement, and develop more positive relationships. Research also shows that these skills can assist students to achieve more success in an increasingly complex world.

How Holocaust Education Can Support Educators

Testimony from Holocaust survivors and witnesses as well as artifacts, like my mother’s ice skates, are useful tools for developing empathy among students. The Echoes & Reflections Holocaust education program offers us reflective ways to develop these important skills, specifically through their collection of visual history testimony provided by USC Shoah Foundation’s IWitness and the featuring of artifacts and primary sources in their lesson plans. Hearing from Holocaust survivors and witnesses is one of the strongest predictors of citizenship values, as reported by the Journal of Moral Education. When a student watches and hears visual history testimony, they become connected to that person in a way that wouldn’t be possible through another medium. With support from Echoes & Reflections resources, educators can work with students to help them do a deep dive into analyzing testimony and be better able to tap into their imaginations and develop their ability to understand another person’s experiences. Visual history testimony can be used to teach listening skills, how to read body language, and how to have an increased understanding of personal emotions.

To facilitate this process, educators can ask their students to focus on particular aspects of a person’s testimony and ask students to answer pointed questions such as:

- “How does this testimony make me feel?”

- “What specifically do I notice about the person’s tone of voice and body language throughout the testimony?”

- “Does the person’s body language change when they are speaking about different incidents and if so, what does this change tell us about the person’s experiences?”

- “What does this remind me of in my own life?”

- “What might I do differently in my own life after seeing this testimony?”

Employing these questions, educators can facilitate classroom discussion, encourage journaling, and foster ongoing reflection projects. Educators can also use these ideas in exploring many other Echoes & Reflections resources such as photographs, literature, poetry, artwork, and other primary sources to better foster empathy.

For me, the ice skates that my mother gave me that day long ago became the embodiment of the reason for the need for empathy. Holocaust education can cultivate that skill in our students so that future generations will foster empathic leaders and improve the world.

About the author: Evelyn Loeb LCSW-R is a retired school social worker and clinician. In addition to serving as a facilitator for Echoes & Reflections, she facilitates programs for the "A World of Difference Institute" and "Words to Action"( Confronting Antisemitism) for ADL.

CURRENT EVENTS

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

We want to believe an attack on Jewish people worshipping in their synagogue is supposed to be a part of history, at least as far back as the Holocaust and on another continent. But, the Tree of Life shooting caused nightmarish memories to resurface and shook Pittsburgh’s residents, especially the city’s Holocaust survivors and their families. Pittsburgh is a city of neighborhoods and communities filled with diverse ethnic groups, religious beliefs, and immigrants from nearly every nation. Residents may argue over the best recipe for pierogis or which Penguin player is the most valuable, but working together for the sake of Pittsburgh binds its residents into one group. Pittsburgh came together before the Tree of Life tragedy, and Pittsburgh has not allowed the tragedy to change its fundamental identity.

Leading up to the first anniversary of the shooting, delicate questions were raised. How does a community mark this date? Nearly thirty different events were planned to commemorate the victims. Some of the events were private – for the victims and their families; for the specific congregations that worship at Tree of Life. Yet disagreements did arise. Wanting to honor the memories of the victims, some people insisted that politics be completely removed from any speeches or comments made during memorial services while others felt that this was impossible, under the circumstances. Agreement was reached on the overall goal: “Remember; Repair; Together” to prevent a similar tragedy in another time or place and to heal as a community.

One year after the Tree of Life shooting our work as Holocaust educators carries increased significance. With the fading memories of the Holocaust and the rise in global antisemitism, educating our students, and, hopefully, the broader community, is our most important tool for shaping a future of tolerance, acceptance, and understanding. As a facilitator for Echoes & Reflections, I am sent to a variety of educational sites. Each group of educators is a product of their own upbringing, their political views, the expectations of the community within which they teach, and the laws of their state. I cannot assume that in six hours of a program I can correct all misconceptions about this history. At the same time, I must reassure those educators that neither can they correct all the misinterpretations that their students believe. We are human, and changing another person’s thinking and understanding takes practice, empathy, and patience.

Hope for a more tolerant and accepting world grows when school administrators and teachers recognize issues within their buildings. Beginning with the 2015-2016 school year, the Act 70 Mandate for Holocaust and Genocide Education was implemented in Pennsylvania. Other states have enacted or are considering similar mandates. As Holocaust educators, this should fill our hearts with joy. At the same time, it should give us pause. Demanding that an individual only mention the words “Holocaust” and “genocide” is ineffective. Handing an educator a curriculum guide that includes a Holocaust lesson or unit does not mean that the educator is informed or prepared to tackle such a complex topic. The rise of antisemitic comments, information, and behaviors in this country and around the world make it clear that not all students, their families, or our fellow educators will accept the facts and welcome the discussions. Administrators and state education officials must provide the designated teacher with emotional support, professional development, and properly vetted resources. When parents, guardians, or community members question or criticize the curriculum, the administration must be prepared to defend vehemently and concisely the reasoning behind the lesson.

Educating people of all ages and situations in life is the best tool we have for fixing the misinformation, misunderstanding, and misrepresentation that have become facts in the minds of a significant number of people. We educators work diligently in our classrooms to create informed and compassionate individuals, and this is valuable and necessary work. But we also recognize that our students’ actions and thoughts are shaped and fueled by their home environment. Family members, religious leaders, and friends all wield power over our student's vision of the world and their definition of “them.” Holocaust and genocide education must reach all members of society if anything is to change. This education includes recognizing and analyzing the propaganda and deliberate lies spread by selfish, fearful, or angry groups and individuals. This education must help to uncover the events and reasons that have encouraged hatred and distrust. Educators often carry the burden of providing a safe environment for students to discuss what they have heard at home or within their communities. At the same time, we educators sometimes think we know and understand but do not always recognize our own blurred vision of facts. If we are to help in preserving and protecting democratic values and institutions, then we must continue to educate ourselves and recognize exactly what we say and do in the classrooms, the faculty rooms, the meeting rooms, and in the world at large. We must continue to help each other to make a positive difference to create a more just world and to prevent future tragedies from occurring.

About the author: Lynne Rosenbaum Ravas retired from teaching and began presenting with the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh's Generations Program. In addition to serving as a facilitator for Echoes & Reflections, she volunteers with the Federal Executive Board's Hate Crimes Working Group and other organizations in the area.

ANTISEMITISM

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

We are clearly living in turbulent times. ADL regularly reports a rise in antisemitic incidents, both here and abroad, and the proliferation of right- wing populist governments continues to be cause for concern. And against the backdrop of increasingly partisan rhetoric in this country as elsewhere, it is incumbent upon teachers to educate our students about the Holocaust and to show them what happens when hateful racist ideology takes hold of governments and even entire societies until only widescale force applied can bring an end to the madness.

At such a moment, it is sobering to teach about Kristallnacht because, in retrospect, we can clearly see the two-day pogrom as a watershed moment, a three-week period when physical attacks upon Jewish lives and property in Nazi Germany were front page news in this country. But, when international outrage and condemnation resulted in no real consequence to the German State, the Nazi leadership interpreted this inaction as a green light to pursue their anti-Jewish agenda.

To those of us aware of this history, the need to push back against antisemitic, racist, homophobic, and or misogynistic rhetoric and policy is fueled both by moral outrage and by the need to protect against an analogous tipping point in our own times.

It wasn’t long after I started teaching Holocaust literature that I found Echoes & Reflections, or rather Echoes & Reflections found me. I attended several of their workshops and seminars at the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center, and I immediately gravitated to their philosophical approach to the subject matter and to their focus on the individual story. Among their many lesson plans is one about the November Pogrom.

The facts of November 9 and 10, 1938, are well known. “From the time the Nazis came to power in 1933 they began isolating Jews in Germany, and passed many laws to that effect. In the first half of 1938, additional laws were passed in Germany restricting German economic activity and educational opportunities…Later that year, 17,000 Jews of Polish citizenship were arrested and relocated across the Polish border. The Polish government refused to admit them so they were interned in relocation camps on the Polish frontier.”[1] Among the many deportees were the parents of seventeen-year-old Herschel Grynszpan, who was living with an uncle in Paris at the time. Outraged by the Nazis’ treatment of his family, he went to the German Embassy in Paris intending to assassinate the German ambassador there but instead killed Ernst vom Rath, a lesser figure in the diplomatic hierarchy. When vom Rath died two days later from his wounds, the Nazis used his death as a pretext to launch attacks on Jewish synagogues, homes, and businesses throughout Germany.

What is interesting and significant about these events from a teaching perspective, is that we have documents related to the attack which make it perfectly clear to our students that the Nazis planned every aspect of the events over that two- day period. For example, Echoes & Reflections materials include a copy of Heydrich’s Instructions to “All Headquarters and Stations of the State Police and “All districts and sub districts of the SD (the Sicherheitsdienst or Secret Police).”[2] Asking students to examine this document and report their findings to their peers allows them to see for themselves the extent of Nazi cynicism and corruption with respect to the rule of law and of human decency. For example, the police were instructed that “only such measures are to be taken as do not endanger German lives or property (i.e. synagogues are to be burned down only where there is no danger of fire in neighboring buildings).”[3]

As a teacher, I find it imperative that students be guided to discover the truths of these documents for themselves by way of careful questions. For example, you can ask them what instructions they would give to their district commanders were they the officers in charge of managing a demonstration in their home city or community. More poignantly, you can ask them what they think Heydrich is saying when he draws a distinction between German and Jewish property. Finally, you can ask them to think about the international situation in 1938 and the reason Heydrich cautions that “Foreign citizens, even if they are Jews, are not to be touched.”[4]

It is both exhilarating and sobering to teach this material to young people. Hearing their outrage and their determination to never let this happen again gives one hope for a better world. And yet, it is sobering to lead these students inevitably towards the later events of the Holocaust and towards the realization that fellow human beings are capable of such atrocities.

This summer I spent three weeks immersed in Holocaust studies in Israel at Yad Vashem. I now know more about the events of the Nazi era than ever before and paradoxically, the more I know about those years and those events, the harder it becomes to teach this history. It breaks my heart to have to tell these wonderful young people how ugly the human heart can be.

And yet, even the student who most hated to hear what happened, wrote of the Holocaust unit last year that he “needed to hear it” and that “only by learning this can we make sure such things can never happen again.”

At the end of this year’s lesson on Kristallnacht, I gave my students a new homework assignment. I asked them three questions about those events:

- Does it make a difference how we label those events, calling them either Kristallnacht or The November Pogrom?

- In what way(s) is your answer complicated by the fact the Nazis called it Kristallnacht and the Jews called it the November Pogrom?

- Who has the right to label the event: the perpetrators; the victims; or a third party such as a historian?

With few exceptions, my students are able to discuss the importance of the name and to connect the events of November 1938 to the long history of antisemitism that continues to this day. Their outrage gives me hope that teaching a rigorous Holocaust program in schools may help build a bulwark against the tide of hateful rhetoric permeating so much of the world today.

About the author: Originally from London, England, Dr. Susan Schinleber taught Cultural and Business and Communication at New York University before moving to Chicago with her young family. After teaching in several area universities, she moved to North Shore Country Day School in Winnetka, IL, where she teaches English, Public Speaking, and Holocaust Studies.

[1] Excerpt from Studying the Holocaust, Kristallnacht. Echoes & Reflections.

[2] From Heydrich’s Instructions, November 1938 in Studying the Holocaust, Kristallnacht. Echoes & Reflections.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

CLASSROOM LESSONS

TEACHING

I teach in a small community in the Midwest. Two years ago I found that many students were leaving our school without a thorough understanding of the Holocaust, one of the most unprecedented acts of inhumanity in modern world history. Located in a homogenous, semi-rural part of southwest Wisconsin, most of my students are unfamiliar with cultural and religious practices different from their own.

After attending a one-day Echoes & Reflections seminar hosted by the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center, my colleague and I felt inspired and equipped to implement a Holocaust elective studies course that not only teaches the history but also challenges students to grapple with the ramifications of prejudice, racism, and stereotyping that are increasingly embedded in our world today.

As an educator, it was important for me to find a sound visual representation of the progression of time during the Holocaust, in hopes that students would be able to easily grasp the overlap of these historical events. With this year’s release of Echoes & Reflections new interactive Timeline of the Holocaust, which was also their first student facing resource, I felt this would be an engaging tool to enhance my course and students’ understanding of how one decision, decree, or act of complicity could impact an entire population. As an English teacher, I appreciate the Timeline’s multimedia incorporation of photographs, primary documents, and personal testimonies to help humanize this complex period.

I first introduced the use of the Timeline through a scaffold process of guided note taking. I provided students with a digital template of the pre-war years and walked them through how to view and “read” the Timeline. I modeled what it looked like to take notes from the Timeline and we discussed the significance of the early years’ events.

Students were instantly comfortable utilizing this learning tool. They engage with not only the material, but also one another during what we refer to as “Timeline Time” as they interact with the online content and discuss the significance of the events. There is a plethora of primary sources available; we do not use a textbook. The students, who crave a tangible resource from which to study, have latched onto the Timeline as a means of creating their own sort of “textbook.”

It can be difficult for a student without a comprehensive world history background to understand all the puzzle pieces that enabled the Nazi rise to power and ultimately the implementation of the “Final Solution”. As a visual representation of years progressing, the Timeline enables students to easily grasp the overlapping of world events and how seemingly isolated events relate to larger scale history. Students interact with the photographs, poems, and audio recordings in a way that helps them build a personal, humanizing connection to the text and the individuals impacted.

The use of the Timeline prompts inquiry-based learning, where the class can question, discuss, and analyze events both in the context of the Holocaust and through the lens of broader world history implications. For example, when students learn that Dachau concentration camp was established in 1933, some ask “why didn’t the world intervene then?” It elicits early conversations about the unprecedented nature of the Holocaust and the roles other countries played throughout the war.

As the course moves from one unit to the next, students have more autonomy with the Timeline. Some work in pairs to read, discuss and analyze the events; others prefer to work alone offering their insights during larger class discussions. Exploring the Timeline and concurrent note taking encourages students to synthesize that information with what they have already learned.

This new resource provides the opportunity for students to read, listen, and connect with individual survivors and victims of the Holocaust. It encourages them to question complicity and celebrate acts of resistance. The interactive Timeline engages students with primary documents and personal artifacts at a level of understanding that no textbook can similarly accomplish.

As we wrapped up this past school year, I felt confident that my students now had a thorough understanding of the Holocaust and were equipped to carry these lessons beyond the walls of the classroom.

About the author: Natalie White teaches Holocaust Studies, 9th grade English, and Creative Writing at Prairie du Chien High School in southwestern Wisconsin. She is currently a member of the Echoes & Reflections Educator Advisory Committee.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

TEACHING

I am fortunate to be able to teach a semester-long senior level Holocaust Studies elective. I teach in a small rural school; thus, most if not every student who elects to take my course had me as their Civics or U.S. History teacher. On day one of the class, I am upfront with what students can expect, or, not expect. They should not expect Holocaust Studies to be the same as my previous two courses. There are no simulations, games, or any of the other multitude of means I typically use to engage students. Students are not going to “pretend” to be in Auschwitz. They aren’t going to build “models” of a concentration camp or wear the Star of David on their clothes to “simulate” what it was like being a Jew in the ghetto. I set the tone for what students should expect: they should expect deep and meaningful learning about a period of history that may upset them and will likely leave them with more questions than I can answer.

My Holocaust Studies course is a relatively new addition to our school’s History Department, and while it is vastly different from my other courses, it continues to evolve. Upon receiving permission to institute the Holocaust course I was advised of the vast teaching resources offered by Echoes & Reflections. Creating a curriculum map was simple: Echoes had already laid out a scope and sequence via their lessons. They had handouts, videos, survivor testimonies, lists of questions to ask, and much, much more. However, despite my good intentions, as a novice Holocaust instructor, I tended to initially focus on the horrors.

In 2018 I was fortunate to be selected as one of 20 United States educators for the Echoes & Reflections inaugural Journey through Poland with Yad Vashem, visiting Holocaust-related sites, during the summer of that year. During our visit to the Galicia Jewish Museum in Krakow I heard something I will never forget as an educator. The Director of the museum advised us that many educators focus on the “car accident” of the Holocaust; in other words - they start with the gas chambers. If we stumble upon an accident scene, what draws our attention are the mangled vehicles, the injuries, and the possible deaths; the Holocaust is no different. What draws attention is often the carnage in and of itself. He iterated that car accidents have a history; something led to the accident. There are stories involved. Again, the Holocaust is the same. The story does not begin in the forest outside Vilna, in the gas chambers of Auschwitz or Treblinka, or in the gas vans of Chelmno - the story is complex and involves human beings with a rich history and culture. It involves perpetrators who made choices, that led to one of the, if not the largest genocide in recorded human history. It involves millions of stories - not all of which can be told in a semester-long course.

After my trip to Poland and visits to sites such as the former Warsaw and Lodz Ghettos, sites of mass graves of Jews murdered by the SS, Chelmno, Treblinka, and Auschwitz, I was invigorated to vastly improve my Holocaust course. I felt a sense of responsibility to ensure I was honoring the victims and survivors alike and took several steps to alter my course. An initial change was to the first unit of study which now focuses entirely on pre-war Jewish life, an aspect completely missing from my previous classes. Further, I amassed a library of non-fiction books written by or telling the stories of survivors. I did this through grants and a Donors Choose campaign. Students are tasked with choosing a book to read and sharing the story with their classmates. While Elie Wiesel’s Night is a masterpiece, there are countless other stories written by survivors, giving different perspectives on the multitude of aspects of the Holocaust. I also include an activity that I was blessed to do for my Poland trip. Each student chooses a victim of the Holocaust, does research, and tells their story to the class, in a sense, providing the victims with a eulogy. I was able to do this for Jewish football player Eddie Hammel as we stood next to Crematorium II in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Holocaust education remains extremely vital. While it is definitely a means to memorialize the victims and thwart Holocaust denial and distortion, it is much more. It is a study of choices, of human resolve and responsibility to others, and a case study of hatred and its consequences. Unfortunately, antisemitism remains prevalent in our society, manifesting itself last fall at the Tree of Life Synagogue Attack in Pittsburgh, the largest mass shooting on a Jewish community in the U.S. Further, racist and discriminatory choices are still being made in today’s world that denigrate and segregate others, and at times, lead to acts of violence.

Thankfully, many states realize the importance of Holocaust education. Twelve states require it to be taught in their public schools, while a dozen other states have bills pending in their legislatures. However, it should not take a state mandate to realize its significance. I implore you, as a teacher, to truly reflect on teaching the subject. Are you focusing just on the “car accident?” Are you asking students to take the perspective of a survivor or victim? Are you simulating anything at all? Are you doing your due diligence and taking the responsibility to ensure Holocaust education is handled in a respectful, proper manner? Teaching about the Holocaust can be challenging for educators, but thankfully, there are programs and resources that exist to support teachers in tackling this important and complex topic.

About the author: Dr. Joe Harmon is a Civics, U.S. History, and Holocaust Studies teacher at Redbank Valley High School in New Bethlehem, PA where he has taught for the last 15 years. He is currently on the Educator Advisory Committee for Echoes & Reflections and is the 2018 Pittsburgh Holocaust Center's Educator of the Year.

CURRENT EVENTS

LITERATURE

On the occasion of Anne Frank's 90th birthday, Anne Frank House Executive Director, Ronald Leopold, reflects on the relationship between the Holocaust and today: whether democratic societies, which were rebuilt with so much care in the shadow of the Holocaust, are in danger and how despite this fear, Anne Frank’s words can guide our youth to a brighter future. This piece was specially adapted for Echoes & Reflections from his keynote speech for the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center on June 5th, 2019.

On the occasion of Anne Frank’s 90th birthday, we recall that the remembrance of the Holocaust is connected to the present and the future.

Anne’s fifteenth birthday would also be her last, because not much later, fate intervenes. On August 4th, 1944, a raid takes place in the building at 263 Prinsengracht, in which all eight people in hiding and the two male helpers are arrested. The people in hiding are deported via the Westerbork transit camp in the East of the Netherlands to Auschwitz and from there to various other concentration camps. Of the eight, only Anne's father Otto Frank ultimately survives the war. The others perish under inhumane circumstances. Anne and her sister Margot succumb to typhus in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in mid-February 1945, two months before the camp is liberated.

But the meaning of the Anne Frank House goes further than the tragedy in which it is rooted. The House also forms a mirror in which we can see ourselves, not to admire our beauty like in a fairytale: Not “mirror, mirror, on the wall, who’s the fairest of them all?", but to be confronted with who we are, what we as human beings are capable of, what the values are that make us human. The fate of Anne and Margot Frank was the work of human hands. It was not the result of a natural disaster, not the work of creatures from another planet, not even the work of one particular type of person. Visitors to the Anne Frank House are invited to reflect on this, and challenged to ask themselves questions, often uncomfortable questions concerning our moral compass. Questions about the choices we make and the consequences they have for ourselves and for others, about the need to protect ourselves against ourselves.

Otto Frank remarked, shortly before the Anne Frank House opened in 1960, that “we should stop teaching history lessons and should start teaching lessons from history.” I don’t assert that we should stop teaching history lessons, but his intrinsic message was clear: history lessons are of little use if they don’t also serve as a mirror for our own actions.

What is the relevance of the Holocaust in the 21st century for generations whose grandparents and great-grandparents were born after WWII? Aren’t the circumstances and events of the past too distant from us? Can they still have a guiding significance in 2019? Or do we soon lose ourselves in slogans, in banal comparisons, in platitudes that sound good but can no longer serve as a moral compass.

History gives us food for thought, not so much because it repeats itself, but because it offers a view of what lies behind human thinking and actions. What motivated people to think and act the way they did? What considerations did they weigh, how do they explain their own time and how do we perceive it in retrospect?

Anyone who has thought about WWII and the Shoah inevitably comes up with the question of how things could have gone so far; at what moment might history have taken a different turn. Historians have already written libraries full about this and undoubtedly there will be much more written. But in 2019 that question also raises an urgent contemporary dilemma related to democratic vigilance: what do we see and hear around us, how do we “read” our own time, how do we interpret the risks? Is our open, democratic society and the rule of law, which we rebuilt with so much care in the shadow of the Holocaust, in danger? Has the world lost its way and are we en route to new tragedies?

Surely it will not happen to us again in a relatively short span of time that we miss the moment to turn the tide of history? That we let the “window to act” pass us by, while the warning lights of the past flash brighter and brighter? Are we going to make the same mistake twice?

“I hope you will be a great source of comfort and support,” Anne Frank wrote in the first sentence of her diary, still unaware of how important this support would prove to be in the more than two years that followed. We can only speculate about her thoughts during the last months of her young life in Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen. Was she able to hold on to her dreams and ideals in a situation of increasing hopelessness? Did she still believe that “. . . people are truly good at heart”, as she had written in her diary a short time before the arrest? Did she gaze at the sky, like she had earlier through the attic window of the hiding place, and think everything is going to turn out alright?

The dreams expressed by Anne Frank implore us to think about who we are and who we want to be, about the world in which we now live and the one we want to live in, about the things that make us human. Her life story serves as a warning and as a source of inspiration, as a guide to achieving a better world, a better future. It is important to realize that Anne Frank's short life began in 1929 in a free and democratic Germany and ended a mere fifteen years later in a world of total barbarism. This malevolence did not begin with the outbreak of WWII, but in the years 1932-1933 with the rapid demise of German democracy and the Nazi takeover of power.

I don't believe we are facing that same inconceivable question at this moment. But I do believe there is every reason to more vigorously defend our open, democratic society and the rule of law. The question I ask is whether we maintain enough of a connection with this contemporary, everyday context. Wouldn’t it be better if we took that context as the starting point for a Shoah-related educational experience instead of a history lesson? Speaking in management terms, shouldn’t we have remembering the Shoah “pulling” from the present instead of “pushing” from the past?

Youth help us fulfil our missions and accordingly build the world of their dreams. They offer us new perspectives, which are accompanied by new connotations. Let us therefore consider how we can actively engage young people, listen to them and welcome them with open arms. It is my experience that there are many very talented and committed young people, sometimes incredibly young, from whom we can learn a lot.

Since the first publication of the Diary of Anne Frank in 1947, it has been read by millions of young people around the world. In the words she penned, they hear the voice of someone their own age, a peer. Her dreams are their dreams.

I want to take you back to April 11, 1944. It’s a lovely spring day in Amsterdam, with a clear blue sky, almost 70 degrees outside, a mild breeze is blowing. A long, bitter cold winter is finally giving way to the first warmth of the year. The trees are budding; it will not be long now before they’re in full bloom. It is a day full of yearning, yearning for everything that has been missing for so long: the warm rays of the sun on your skin, fresh air, the smell of nature awakening. Anne Frank is at her desk in the musty annex writing one of the longest and most moving entries in her diary.

A break-in downstairs in the building makes her once again realize that she’s in hiding, makes her think about being Jewish and what that means to her. She’s scared but determined to be brave and strong. She’s ready for death but wants to live, wants to make her mark on the world. She reflects on who she is and who she wants to be: a Jew; Dutch; a woman with inner strength, a goal, opinions, religion and love.

“If only I can be myself, I'll be satisfied.”

With these simple words Anne Frank reveals something very personal to us. On that beautiful spring day, she doesn’t share an identity claim with us, but the desire for space and the freedom to discover and develop herself. Her diary is the consequence of that search. She has been locked up in a small space with seven others for more than two years, continually discovering herself but always realizing that she is part of a group of people who are dependent on one another. She wants to make her voice heard, she has strong opinions, but is also vulnerable and prepared to change her point-of-view, even if this is easier said than done. Each time she asks herself questions and presents herself with dilemmas. And she realizes if she must get along with the seven other inhabitants of the Secret Annex, that she sometimes has to comply with their wishes.

The very last sentence of her diary speaks volumes: “. . . [I] keep on trying to find a way to become what I’d like to be and what I could be, if . . . if only there were no other people in the world.” But other people live there as well. “If only I can be myself” Just like in the diary, not as an identity claim, but as an individual desire and a democratic endeavor to ensure that everyone has the opportunity and freedom to discover and develop themselves, while keeping in mind that other people live in the world. Whoever reads Anne Frank’s diary cannot help but think about the dilemmas this presents, about what kind of attitudes and abilities are required of us. This isn’t going to give us the best of all possible worlds, but hopefully it will spare us the Hell that Anne Frank, Margot Frank, and millions of others were forced to endure. They were not only prohibited from being their true selves, but from being at all.

About the Author: Ronald Leopold has been the executive director of the Anne Frank House since 2011. Leopold held various posts at the Dutch General Pension Fund for Public Employees and was involved in the implementation of the legislation regarding war victims. Leopold lives in Amsterdam with his wife and daughter.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

TEACHING

Is it possible to teach respect for racial and religious differences?

This is a question I hear a lot from teachers who are committed to social justice but frustrated by mounting evidence of blunt and sometimes deadly prejudice. ADL recently confirmed that since 2016 antisemitism has dramatically increased in the U.S. and abroad. The Southern Poverty Law Center (SLPC) reports, “a surge of incidents involving racial slurs and symbols, bigotry and the harassment of minority children in the nation’s schools.”

It’s a fair question, and a rational one. Does classroom instruction on racial and religious tolerance make any difference at a time when intolerance is on the rise?

It does, and scholars have documented that studying the Holocaust and racial equality cultivates respect for diversity and fortifies democratic ideals. Teaching about the Holocaust is one of the most powerful ways to help young people understand the dangers of unchecked biases, and how, even in modern, democratic societies, these biases can escalate to catastrophic proportions.

In fact, the nation’s first program of anti-bias education was developed during World War II to “inoculate” American youth against Nazism. As one teacher insisted in 1941, “The most vital program of our country today and one, therefore, especially important to our schools is the promotion of the doctrine of tolerance as a means of knitting our nation into one closely integrated unit.” Scholars including the anthropologists Franz Boas, Ruth Benedict, and Margaret Mead developed K-12 curricula—including comic books and animated films—designed to teach students that Judaism was a religion, not a race, and that there was no such thing as racial superiority.

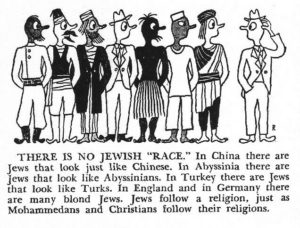

Figure 1 An image from The Races of Mankind, by anthropologists Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish, in 1944. Anthropologists during World War II believed that teaching the scientific definition of race would undermine Nazi racial doctrines and fortify American democracy.

Times of crisis, like World War II, force educators and politicians to recognize that unchecked bias is a direct threat to American democracy. That is why antiracist education became so popular during World War II, as I document in my book, Color in the Classroom: How American Schools Taught Race, 1900-1954.

It’s also why anti-bias education is such a hot topic today. Anti-bias education is designed to address prejudices including racial, religious, ethnic, gender, sexuality, social class, and immigration status. Teaching young people to identify and resist biased attitudes usually includes a study of historical events where small prejudices grew into acts of discrimination, which, in some cases, escalated into state-sponsored violence and genocide. The Pyramid of Hate found in Echoes & Reflections offers students a graphic representation of this danger.

As the Director of the Holocaust, Genocide, and Human Rights Education Project at Montclair State University (MSU), I have seen interest in our anti-bias programs surge since 2016. Our Holocaust education workshops fill up with a diverse group of people including not only K-12 teachers, but also school administrators and college students. Other human rights programs such as Native American environmental justice and support for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGTBQ) students are also popular. Educators are ready to teach lessons emphasizing respect for diversity and equality—what they need is more support.

This is where higher education has a vital role to play. American colleges and universities can support stronger and more robust anti-bias education in our K-12 schools. The question is, how?

First, universities can host professional development workshops such as Echoes & Reflections for K-12 educators and student teachers, including alumni. These workshops offer hands-on training in how to teach about the Holocaust—a topic that many K-12 teachers are nervous or unprepared to talk about. Participants gain access to online teaching materials including primary historical documents, photographs, interactive maps, and survivor testimony and are provided with models of how to incorporate these texts into effective lessons. Special thematic workshops on topics like antisemitism or immigration help teachers make direct connections between the Holocaust and current events. At MSU, we find that blended workshops with K-12 educators and student teachers create especially dynamic spaces. What is more, when a prominent university hosts a social justice education workshop for local teachers, it signifies to the broader public scholarly support for anti-bias education.

Second, scholars and university administrators can advocate for legislation requiring anti-bias education in public schools. New Jersey is a leader in this area. In 1994 state legislators mandated education on the Holocaust and genocide. Earlier this spring, New Jersey passed a law requiring instruction on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender social, political, and economic contributions. These laws provide critical support for anti-bias education in public schools, especially in communities where such lessons may be seen as controversial. In New Jersey, teachers can point to state law and continue the hard work of teaching children to understand and respect one another’s differences. The New Jersey Commission on Holocaust Education coordinates anti-bias education through a network of centers located the state’s public and private colleges and universities. Despite New Jersey’s success as a leader in anti-bias education, few other states have similar structures in place. If more states required and supported anti-bias education, it would expand training, resources, and support for K-12 teachers.

Figure 2 A Human Rights Education Intern at Montclair State University teaches about the Syrian refugee crisis to local middle school students.

Third, universities can mobilize our greatest resource to promote anti-bias education—our amazing students. MSU hosts a Human Rights Education Internship, where undergraduate students can apply to train as professional human rights educators. Interns select a specific human rights issue and spend a semester learning about human rights law, researching their selected topic, developing an effective lesson on it for a secondary school audience, and then teaching it in a local school. This spring we hosted a “Human Rights University for a Day” at Montclair High School, where interns taught lessons on Holocaust denial, the gender wage gap, juvenile incarceration, school segregation, religious tolerance, the Central American refugee crisis, the healthcare crisis in Venezuela, child labor, and colorism. The internship serves two purposes—first, it allows undergraduate students to train as human rights educators, skills they will carry with them into their future professions. Second, the internship sends undergraduate students as human rights education ambassadors into local public schools, where they not only teach about important subjects that are not necessarily part of the regular curriculum, but where they also model what it looks like to be an engaged, socially conscious college student. Put plainly, human rights education interns inspire youth to go to college! The results are inspiring for both our interns and the high school students they meet, and help our university forge new relationships with our local community.

Is it possible to teach respect for racial and religious differences in K-12 schools? The answer is yes, but our teachers need more help and American colleges and universities are uniquely positioned to provide it.

About the Author: Dr. Zoë Burkholder is an Associate Professor of Educational Foundations at Montclair State University, where she serves as Director of the Holocaust, Genocide, and Human Rights Education Project (On Facebook: @MSUHumanRights). She is the author of Color in the Classroom: How American Schools Taught Race, 1900-1954 (Oxford University Press, 2011). She may be contacted at burkholderz@montclair.edu

BYSTANDERS

CLASSROOM LESSONS

When introducing myself at an Echoes & Reflections training, I often tell the teachers that I have the best of both worlds: I teach high school students by day and work with teachers and adults at other times in professional development to educate them about the lessons of the Holocaust.

Having taught high school English for the past 27 years has been rewarding, allowing me to learn along with my students and to learn about them. In 1999 I developed a semester-long Holocaust Literature course, which sent my teaching in a new direction. For someone who hadn’t even learned about the Holocaust in high school, I had a lot to catch up on. I took courses, read voraciously, watched hours of videos (on VHS, nonetheless!) and attended every training I could find. Then I became a Museum Teacher Fellow with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and soon after discovered Echoes & Reflections, when it emerged in 2005. One of the components about the Holocaust that has always intrigued me is that new information is still coming out, 86 years after it began. New research, new perspectives, new voices and narratives arrive almost daily; thus, I can never teach the subject the exact same way. And this is one of the components I love about Echoes & Reflections; they are constantly updating, changing, and even adding new programs (like the Connecting the Past with Today: Jewish Refugees and the Holocaust, or their session on Contemporary Antisemitism), making the lessons relevant to current topics and scholarship.

Most of my trainings for Echoes & Reflections take place in the Southwest region, and I travel to Texas often; in fact, I have joked that I probably need to get a driver’s license there! I have had the pleasure of presenting at the Dallas Holocaust Museum’s three-day conference several summers, and after the second conference, I realized that many teachers return year after year (a testament to the quality of the program). Thus, I needed to create new agendas each year, focusing on different units in Echoes & Reflections. Last year, for example, I chose a unit that I use in my own classroom but one that I had never utilized fully in a training: Perpetrators, Bystanders, and Collaborators. It is a strong unit, and complex. It is difficult and potentially imprudent to discuss perpetrators. Echoes & Reflections pedagogy is geared to focus on the stories of victims and rescuers because we want their stories to be heard; to honor their memories. It can be challenging to balance addressing perpetrators and collaborators, while still maintaining integrity and respect for the victims.

The Echoes & Reflections unit on the subject introduces the topic in a sensitive manner and supports educators in responsibly introducing this complex topic. One perpetrator mentioned in the unit is Salitter, a German official who was in charge of a train which held Jews being deported to a camp. His report allows students and teachers alike to grapple with tough questions. Did he have to do this job, or did he choose to? Why is his tone so clinical? Does he ever feel emotional about the situation? Does he even see the victims as people, as individuals who had full lives before this terrible event? We then read a complementary piece, a victim’s account of the same experience, and discuss how it differs from the report and adds a more human element. This opens another discussion about choices that people made to collaborate or perpetrate, or not. We grapple with the complexities of these documents and the feelings they arouse, and they force us to consider our own choices we make, lending to a great discussion—not on what we might have done in Salitter’s case, for that is an exercise in futility--but thinking about choices we make in our daily lives. How do we make those decisions? Do we even consider how others might be affected? Do we think of consequences only after a crime or bad deed has been committed?

This is not an easy topic to teach, nor should it be. However, my experience with Echoes & Reflections, as a facilitator and classroom teacher, has made it easier for me to get the information and learn ways to use it in the classroom, utilizing lessons that engage students in our ever-changing world.

About the author: Kim Klett has taught English at Dobson High School since 1991. In addition to being a trainer for Echoes & Reflections, she is a Museum Teacher Fellow of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Deputy Executive Director of Educators' Institute for Human Rights, a Carl Wilkens Fellow, and secretary on the board of the Phoenix Holocaust Association.

ANTISEMITISM

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

This article originally appeared in Education Week

The Holocaust is ancient history for many students

On May 2, Holocaust Remembrance Day (or Yom HaShoah), we remember the millions of Jewish and other victims killed during the murderous Nazi reign in Germany. Sadly, we only need to consider the shooting at a synagogue this past Saturday in Poway, Calif., to understand the importance of using classroom time to educate and reflect on this horrific period in history.

Not even two months ago, a photo showing students making a Nazi salute over a swastika made of Solo cups at a weekend party garnered extensive news coverage. This image came on the heels of another viral photo of a group of laughing young men who appeared to make the Nazi salute prior to a school dance. Swirling around these events have been Jewish cemetery desecrations, hate-filled graffiti, and even swastikas drawn in blood. Amid it all, we still grieve for the Jewish congregants shot dead at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh last fall—and now Poway.

I am sure many have felt as I do: What is happening? What can I do about it? On an intellectual level, I know this is not new—hatred, violence, and targeting of the "other" have always been with us. The acts of violence may ebb, but these feelings are always there.

On a professional level, having spent the better part of 25 years working in anti-bias and Holocaust education, I feel some sense of personal failure. I know these incidents of antisemitism and other forms of hatred do not reflect the values and beliefs of the majority of people, but I can't help but question if the work I have done has mattered.

I recall my former colleague who would say that the work to counter hatred, antisemitism, and racism could sometimes feel like having a tiny pink Baskin-Robbins sample spoon, trying to chip away at a mountain of mistrust, fear, anger, ignorance, resentment, and downright apathy. She didn't use this analogy to discourage, but to inspire: If we all worked together, even with the smallest of tools, we could get there.

I've always framed my work, as many educators do, in three phases of impact: What do we need to know about an issue or topic, why should we care, and how can we act to make a positive difference? Or, in more poetic words, how do we inform the head, move the heart, and motivate the hands?

For those teaching the Holocaust, these three concepts could not be more vital and interdependent. What do we want students to know about this history? If you want to understand the why and how this genocide could have happened, you need a foundation of the what. The Echoes & Reflections Partners toiled for a year to distill the core historical content that now forms our 10 classroom units. Our goal was—and is—to guide teachers to build this essential knowledge with their students and to ask those critical questions of why and how at every step.

But knowing isn't enough; students have to care. The Holocaust is practically ancient history for many young people, and, for the majority of people in the United States, it is not their history. It's remote, it happened somewhere else, and it's over. This is where we must teach about the Holocaust as a human story. We should bring this knowledge to life through the integration of visual history testimonies and primary sources. We want young people to see, listen, and come to know that these were real people who had desires, dreams, hopes, and lives that were just waiting to be lived.

I could never guarantee that students who watched a testimony of a survivor describing his arrival at Auschwitz or read a poem by a girl left alone in the Lodz ghetto would reject the Solo Cup swastika game. But maybe, just maybe, they would make a different decision in that moment.

Which brings us to action. How do we create and inspire a sense of personal agency so that in the face of hatred or antisemitism—or when anyone is excluded or "othered"—we don't just walk away or swipe the screen?

When I began my work in this field, this step used to be primarily about an in-person response: Will you speak up if someone is being taunted? Will you call out an antisemitic comment or joke?

Today, for most adolescents, these moral choice moments are experienced online and at lightning speed. Does this make it easier or harder to speak (or type) out? Does it fuel a level of insensitivity to these issues that carries over to real-life choices and decisions? Does an intervention online have more or less power to impact the person who is being offensive?

These are the questions I have been wrestling with these past few months. On Yom HaShoah, this sacred day of remembrance for all those who perished during the Holocaust, I hope to start to find some answers. I will work to learn more about the experiences and perspectives of the adolescents in our country and what is driving some of them to engage in or ignore hurtful behavior—and how can we inspire more to stand up.

And I encourage everyone, not just educators, to do the same. At a time when it feels so hard to have these tough conversations, isn't it that much more important that we try? If we want our children to care, we must first care enough to listen to them.

About the author: Lindsay J. Friedman is the Managing Director of Echoes & Reflections. Previously, she served as the national director of the ADL's A World of Difference Institute.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

TEACHING

UNCATEGORIZED

As we enter Genocide Awareness month in April, we offer our community an inside perspective on how to approach the important, yet challenging subject of the Holocaust in the classroom. Seasoned Echoes & Reflections teacher Lori Fulton, English 11 & Technical Reading and Writing instructor at Mattawan High School in Mattawan, MI, lends her perspective and approach to inspire students with these lessons from history to prevent future acts of hate.

Why do you feel it is necessary to teach about the Holocaust?

Teaching students about the Holocaust should be the responsibility of instructors in all secondary schools. As a high school English teacher, I am amazed at how little my students know about this subject. Sure, they know a little about Hitler and gas chambers, but they have no idea how the Versailles Treaty connects to the Nazis, most of my juniors assume all the death camps were in Germany, and none are aware of the 10 Stages leading to genocide.

More importantly, the Holocaust requires studying to prevent genocide from happening again. We are raising a generation of students who will one day rule the world. They are subjected to the constant noise of social media, which unfortunately at times, is accompanied by hate speech. They all have a sort of cyber-courage that makes them vulnerable to saying things online they would never say to anyone in person. As a result, there is almost a sense of acceptance of anything online. With that potentially comes the notion of denying the Holocaust, something that must be addressed as wrong and dangerous.

We live in a world where words breed hate, not just on the internet but from the mouths of our politicians. We see vandals desecrating Jewish cemeteries and tagging buildings with swastikas, as well as Americans in parades wearing Nazi-like uniforms; we hear of news of a person going into a synagogue and killing innocent worshippers. Our students see and hear all of this and need to know that hate didn't end or begin with the events of World War II.

Why should I teach the Holocaust? If I don't, who will? Who will provide students with the resources, the knowledge, and the ability to help them make up their own minds about that horrific time in world history? It is my duty and my desire to help students realize genocide can happen again and, as the next generation of Americans, they must do everything in their power to stop it.

What are some recommended strategies for teaching such a sensitive theme? How do you approach this important yet complex topic with your students?

We must approach the subject of the Holocaust with students in a sensitive manner to help them understand, remember, and hopefully eliminate future genocides. This means sharing the stories of those who faced life-and-death situations simply because of who they were. We cannot replicate their experiences through simulations, but we can learn from the experiences of others.

I start by introducing the idea of antisemitism. From there, we study pre-war Jewry, the Treaty of Versailles, then how Hitler rose to power, steps leading to genocide, the Final Solution, resistance, liberation, and what happened to European Jews following WWII.

Furthermore, personal stories are essential ingredients in the teaching of the Holocaust. The testimonies on the Echoes & Reflection's website and USC Shoah Foundations’ IWitness powerfully say what I cannot say.

Holocaust Films, as well as literature, are also great tools to reel in my students. Most of them are visual learners, so having new resources available to meet their learning styles is important to teach this complex subject.

I have traditionally shown Schindler’s List when teaching about the Holocaust. I cannot think of a better movie for my juniors to really set the stage for deeper learning and truly connecting to the story of Schindler and the Jews he saved. We discuss many questions that arise from the film: Who else is considered “Righteous Among the Nations” in the eyes of Yad Vashem--and what does that mean? What would have happened if Schindler's ultimate objective to save Jews was discovered? What happened to the survivors after liberation? Would I have the courage to save someone if it meant my possible death?

Finally, I take my juniors to the Holocaust Memorial Center and Museum in Farmington Hills, Michigan. For some of them, they have never been much farther than the next town over. A docent takes us through the museum to study the artifacts, as well as (again) the stories of individuals. This comes to the penultimate point of the unit where a survivor speaks to my students about his or her experience. This is life-changing for my students. Many are in tears by the end of the survivor's story.

If students are emotionally drawn into this experience, I feel I've done my job. They have seen a bigger picture of the Holocaust and genocide than they have ever seen before. History has come alive for them, but more importantly, they have come full circle in their learning experience. Most of my students will say the unit is the one they will never forget and graduates who return to visit express similar sentiments.

What specific resources would you especially like to highlight that support you in teaching about the Holocaust?

After spending several weeks last summer in Jerusalem as part of Echoes & Reflections Advanced Learning Seminar at Yad Vashem, I have gained deeper insight into resources that can support classroom instruction on the Holocaust. These include:

- Echoes & Reflections’ new timeline helps show the events leading up to when the Nazis came to power, as well as what happened as a result of it.

- Echoes & Reflections’ companion resource for Schindler's List, which includes survivor testimony, new handouts on historical context, and a series of discussion questions and writing prompts add to the unit and unpacking the film.

- The ADL Global 100 of Anti-Semitism. Students are shocked by the percentages of people with antisemitic attitudes in countries around the world. They simply cannot fathom the numbers. It also brings to light that hate still exists around the world.

Nothing, however, is more important than the testimonies of survivors as far as I'm concerned. Their recollections bring a perspective nothing else can-- not books, not films, not internet sources. The pathos of survivors’ experiences motivates my students to keep learning. Overall, the resources available from Echoes & Reflections and their Partners help enhance my unit on the Holocaust and genocide, making it relevant and inspiring to my high school juniors.

This site contains links to other sites. Echoes & Reflections is not responsible for the privacy practices or the content of such Web sites. This privacy statement applies solely to information collected by echoesandreflections.org.

We do not use this tool to collect or store your personal information, and it cannot be used to identify who you are. You can use the Google Analytics Opt-Out Browser Add-on to disable tracking by Google Analytics.

We currently do not use technology that responds to do-not-track signals from your browser.

Users may opt-out of receiving future mailings; see the choice/opt-out section below.

We use an outside shipping company to ship orders. These companies are contractually prohibited from retaining, sharing, storing or using personally identifiable information for any secondary purposes.

We may partner with third parties to provide specific services. When a user signs up for these services, we will share names, or other contact information that is necessary for the third party to provide these services.

These parties are contractually prohibited from using personally identifiable information except for the purpose of providing these services.

1. You can unsubscribe or change your e-mail preferences online by following the link at the bottom of any e-mail you receive from Echoes & Reflections via HubSpot.

2. You can notify us by email at info@echoesandreflections.org of your desire to be removed from our e-mail list or contributor mailing list.

English

English