HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

TEACHING

Sites of memory illustrate the interactions, tensions, and complicated layers of how the past and present have selectively been remembered, forgotten, and silenced over time.[1] These sites and their meanings, crafted and produced by particular individuals or groups through symbolism and aspirations for how the site should be understood, are malleable, transforming and evolving within the societies in which they exist and by those who consume and interpret these sites.

“This is the site for the American memorial to the heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto Battle April-May 1943 and to the six million Jews of Europe martyred in the cause of human liberties.” -Plaque, Warsaw Ghetto Memorial Park, Riverside Park, New York City, New York

Described as a site of memory meant to “ke[ep] alive” the memory of the six million Jews who perished from what would eventually be known as the Holocaust, the Riverside Park memorial was erected in October 1947, catalyzed and envisioned by the American Memorial to Six Million Jews of Europe, Inc., as step one of a large, disruptive, contemplative space visible from the surrounding Western Manhattan, New York area.[2] In its original conception, this space was supposed to force those around to confront and reflect on the bravery of Jewish victims of the Nazi regime. Specifically seeking to memorialize the courage of Jews in the “Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto,” now traditionally referred to as the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, to denote the heroism of those who fought back despite hopeless circumstances, this memorial represents one of the first Holocaust sites of memory in the United States. However, over seventy-five years later, this memorial, known today as the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial Park, remains in its initial physical manifestation, seemingly blending into the landscape as a plaque on the ground as opposed to causing an active remembrance and education of this genocide. How does one of the first Holocaust sites of memory in the United States become just another part of a park, and how can consumers of this site and others work to elevate our understanding of hard histories?

When I visited the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial Park, I was immediately struck by the dedicated protection for the plaque. As I teach in my courses, fences surrounding sites of memory not only keep things out, but they have the potential to ‘gatekeep’ memories in. I wondered about the legacies of vandalism and natural degradation that might have brought about the need for a fence to protect the physical plaque and the people it represents as well as the experiences and identities of those who were killed in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising whose stories we might never know. I questioned if any pro-Nazi groups had ever paraded around this memorial to attempt to change its signification and celebrated the fact that even if so, the community of proponents and supporters of this site have remained steadfast in honoring the Jewish victims of the Holocaust. I thought about the Jewish tradition of leaving stones on gravesites to signify visitation and remembrance when seeing a few littered rocks on and around the plaque, curious about how this practice shifted the meaning of the site upon my visit. I reflected upon what the memorial silenced - other moments of resistance and loss fallen through the cracks because of the heightened focus of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising - and how many of the narratives of suffering and heroism, struggle and resistance during the Holocaust will never be told.

These unique interpretations emerged through my specific understanding of the Holocaust, of sites of memory, and of my fragmented knowledge about the various iterations of this site at a particular moment in time. Other visitors will consume the site in similar and different ways, due to their overlapping and contrasting knowledge base coming to this site, meaning that we all play a part in the meaning making process. In experiencing sites of memory, we all share a role in how the past and present converge, diverge, and attempt to be understood.

As a consumer in 2023, I was greatly influenced by the current moment of sites of memory in the United States. The United States has been reckoning with its own violent past and injustices, particularly the legacies of the institution of slavery and its long-term consequences on the Black population and genocide perpetrated against Indigenous communities. Demands to interrogate and dismantle the contemporary public landscape have demonstrated that monuments, memorials, and museums are being reinterpreted today, serving as representative symbols of the present and future as well as relics of the past. These historical reinterpretations have also included a deep reflection of the United States’ role in the Holocaust. The current exhibit in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., Americans and the Holocaust, and Ken Burns’s new documentary series, The U.S. and the Holocaust, challenge the traditional narrative of the United States as global liberators of concentration camps by emphasizing the xenophobia and non-interventionist mentality permeating the United States during the rise of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust. Studying various Holocaust memorials and museums in the United States causes us to question why these sites exist and how they came to fruition.

The remnants of water on the plaque created a literal reflection. While looking back and thinking about the victims of the Holocaust, the reflection also allowed me to see the branches of a tree above, symbolizing, to me, a journey of rebirth and regrowth.

Contextualizing the ideologies and erection of sites of memory allows us, as consumers, to root ourselves in the original conceptions and unavoidable evolutions of these spaces and their meanings over time. Understanding the producers and their assumed audience, along with the narratives and memories honored and silenced in these spaces, informs our experience and interpretations as consumers. The next time you see a plaque on the ground, look at it, read it, interpret it, experience it, and commit yourself to learning more about how these sites promote particular versions and memories of the past for our present and future. You are a part of the meaning making process; your interpretations matter!

About the author: Tyler J. Goldberger is a History PhD candidate and Teaching Fellow at William & Mary. His scholarship explores historical memory, human rights, transnationalism, and US-Spain relations in the 20thcentury.

[1] Maurice Halbwachs, On Collective Memory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1925); Pierre Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire,” trans. Marc Roudebush, Representations 26 (Spring 1989): 7–24.

[2] “Jewish Memorial to Rise on Drive,” New York Times, June 19, 1947.

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

SURVIVORS

“I always knew I was Jewish, but in our house, there was no religion practiced really.” These are words from Holocaust survivor Margaret Lambert, describing what her life was like in Germany before Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. It’s a sentiment I can relate to as I also have always known I was Jewish. There was never any need to give intentional visibility to this identity through custom or tradition. My non-English name ascribed to me at birth, given out of remembrance, to hold onto what my mother left behind in her homeland, instilled in me an immutable awareness of my cultural roots.

The “always knowing” clings more tightly as a third-generation survivor, as the Holocaust has also always been a part of unconscious memory. I don’t recall a moment during a classroom lesson, watching a movie, or in conversation where I first acquired knowledge about this catastrophe—it is one that has always been with me, a specter of my past. My maternal grandfather’s survival story was ever-present in my childhood. It was a tale drenched in the heroism and bravery of a young man who fled Poland (now Belarus) by sea to Palestine in 1937, illegally jumped ship and joined the British army as a spy to fight against the Axis powers—forces that would be responsible for the deaths of so many of my other relatives. It never eludes me that my very existence, my ability to live freely and have endless opportunities in this country, is a result of his fortuitous escape.

In some ways I am envious of those who have had the privilege to be introduced in a well thought out and planned way to this pivotal history. That there are those who can pinpoint a specific moment when they learned about the Holocaust, designating a before and after, a division of this time in their lives. These are people who have a mechanism to assess their perspective on humanity prior to knowing vs. now having the knowledge cemented, which can hopefully offer deeper reflection on the timeless lessons of this history.

It's not that I don’t have memories about moments of witnessing, experiencing an awareness of the Holocaust, or that it wasn’t ever presented to me in a classroom setting, but they often are fraught with discomfort—it feels at times too personal. When I was 10 years old, I visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and wandered through Daniel’s Story—on my own. I distinctly remember entering the concentration camp section of the exhibit, my lungs filling with a heavy cold air, a sudden suffocation of dread and panic, the thought of “this could have been me” creeping through my mind. I raced out of there as fast I could, wanting to shed whatever memory or passed down trauma I may have inadvertently absorbed. This is not because Daniel’s Story is one that should not be viewed by young people, but it does make me wonder if there are deeper considerations as to how a generational survivor might be impacted by certain Holocaust learning experiences.

Despite the challenges of remembrance, there is the question of responsibility. What is my duty to share, uphold, the memories of a story, that isn’t really my own lived experience, but one that seems to reside firmly in my DNA? “Never Forget” has been, still is, and will always be a reverberating phrase in my consciousness. While there is no clear beginning to the memory, the not forgetting is the foundational tenet of my Holocaust education. I firmly believe in this notion, but over the years I have encountered a tension between the “knowing'' and the actions I am expected to take with this knowledge, particularly if it involves sharing my own ancestral trauma. Perhaps it’s because I don’t want myself or my family to be defined by tragedy, by the weight it inevitably carries.

And yet, the work I do is a reminder that the action of remembrance can take different forms. I may not be openly sharing my family’s history on a regular basis, but it is because of my background that I feel an unexpected comfort, sense of ease even, in being one to support educators and students in learning about the Holocaust. I am contributing to a program that provides Holocaust education in a responsible and effective manner, which perhaps is my own way of moving “safely in and out”—an experience I severely lacked in my youth. And, with time, almost six years at this point, I am beginning to allow more of the personal to seep into the work, like seeing myself through Margaret, or through the multitude of visual history testimonies our program provides. It is perhaps through this ongoing experience, that at some point I will be able to move towards a greater security to openly share my family’s Holocaust story.

About the author: Talia Langman is the Media & Communications Specialist for Echoes & Reflections.

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

SURVIVORS

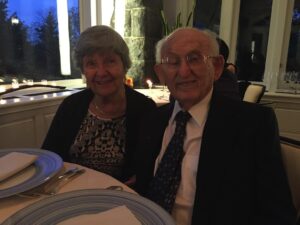

After surviving the Holocaust, then living an extraordinary life, my grandfather, Herschel (Hersi) Zelovic, lost his life to Covid-19 on November 11th at the age of 93. On this day, my grandfather was one of the 1,431 Covid-related deaths in the United States. As I am writing this blog—not even three months after his death—there have been more than 400,000 reported deaths nation-wide due to this terrifying disease.

After surviving the Holocaust, then living an extraordinary life, my grandfather, Herschel (Hersi) Zelovic, lost his life to Covid-19 on November 11th at the age of 93. On this day, my grandfather was one of the 1,431 Covid-related deaths in the United States. As I am writing this blog—not even three months after his death—there have been more than 400,000 reported deaths nation-wide due to this terrifying disease.

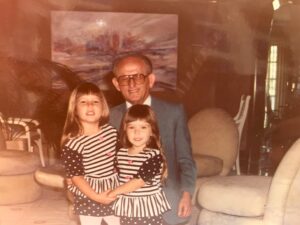

Both of my maternal grandparents survived the Holocaust, and it is their history and experiences during this tragedy, retold to me over time, which influenced and inspired me to pursue a career in Holocaust education. And, just as Echoes & Reflections pedagogy emphasizes the importance of translating numbers from the Holocaust into personal stories to promote empathy and understanding, I am committed to keeping my grandfather’s story alive, and ensuring that his death is not just an awful statistic from the Covid-19 pandemic. In fact, my pursuit to tell his story began long before his unfortunate passing.

As a young adult, my mother asked my grandfather to write down his memories of his hometown, his childhood, and his experiences during the Holocaust so that she could one day share them with her own children. In response to his daughter’s wish, on September 20, 1982, my grandfather began writing what became 153 pages of testimony. On April 27, 2005, my three sisters and I presented my grandfather with a typed up, bound version of his memoir, with the dedication, “On the 60th anniversary of your liberation day… you have lived a life of strength and perseverance, filled with undying love for your family. You are a model to all of us.”

As we approach International Holocaust Remembrance Day—the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, I recall that for my grandfather, the pivotal event of liberation was the turning point that opened up the possibility of a fulfilling life. It is the part of his story I remember most vividly. It stands out most to me because of the clarity, emotion, and passion with which he himself tells about the experience. It also highlights for me that his ability to pass down his story firsthand provides me with the privilege – and the responsibility - to tell his story and share my memories in his absence.

In an effort to remind myself of all the details of my grandfather’s experiences during the Holocaust, I turn to his autobiography again. I also look at old photos and at recent photos, I watch old film and new video, I laugh and cry with family, I watch video testimony and reread his written testimony – all to build a complete story that I can share with my children, as well as with friends, colleagues, and with the wider community of Echoes & Reflections educators.

My Grandfather’s Story

Herschel (Hersi) Zelovic was born in 1927 in Munkacs, Czechoslovakia, to a large family of eight children. In 1938, the Hungarians occupied Munkacs and that is when restrictions against Jewish-owned businesses began and displays of antisemitism grew.

In March 1944, the Nazis occupied Munkacs. Two weeks later, boys and men over ten years old were forced to build the ghetto in town. Then after a few weeks, my grandfather was sent on a train to Auschwitz with his family.

After 11 days in Auschwitz, my grandfather was sent to Warsaw to clean up the damage after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. He was then sent to Dachau to build a railroad and an underground factory and rebuild bombed railroads in Munich. While he was separated from his parents at their arrival in Auschwitz, my grandfather and his brother, my great-uncle Willy, surprisingly were never separated, which gave them both hope and the will to survive.

In April 1945, rumors went around that the American army was getting closer and so camp guards rounded the prisoners up and loaded them onto a train. A German military train pulled up next to the train full of prisoners in the hopes that the incoming air raid would not attack with a civilian train nearby.

However, airplanes appeared and shooting began. The prisoners were ordered off the train and with all the commotion, my grandfather, his brother, and twelve other prisoners escaped into the forest together. After walking into the evening, the group fell asleep and were awoken by an SS officer who ordered them to walk to the nearby village.

The SS officer left the group with the mayor and then went to round up more runaway prisoners. In fear of spreading Typhoid fever to the town, the mayor advised my grandfather’s group to run toward the American army who would help them.

On their way, they found a deserted looking farm and spent a few nights in the hayloft. They shared the boiled potatoes with the pigs until they were discovered by a kind woman who began bringing them hot soup, milk, cheese, and bread. Once the German army pulled out of the area, my grandfather and his friends were able to walk around freely. American soldiers then entered the town and the group was taken to a hospital to recuperate and recover.

In my mind, what happened next is the most beautiful part of the story… the journey through liberation.

Hersi and Willy discovered that seven out of eight siblings had miraculously survived! After the war, one went to Brazil, several to Palestine, and three to England. My grandfather went to England and lived in a home for orphaned boys. There, he met and fell in love with my grandmother Renate, who had come to England from Germany on the Kindertransport when she was six years old.

They married and moved to New York City, surrounded by family and friends from Europe. They built a happy life together; my mother was born, then there were grandkids, and two great-grandchildren – a life and legacy made possible after liberation.

They married and moved to New York City, surrounded by family and friends from Europe. They built a happy life together; my mother was born, then there were grandkids, and two great-grandchildren – a life and legacy made possible after liberation.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Although I am deeply saddened by my grandfather’s passing, this loss only further motivates me to keep his story alive through my work in Holocaust education. With the dwindling population of Holocaust survivors still with us, it is the responsibility of the second generation, third generation, and educators to share personal stories from the Holocaust.

It is my wish that you will pass on my grandfather’s story and those of other survivors to bring lessons of hope and resilience to future generations, as well as to provide a cautionary tale for allowing antisemitism and hate to flourish in society.

To support your teaching about liberation and the experiences of survivors, access Echoes & Reflections lesson plans on these topics here.

About the author: Ariel Behrman is ADL’s Director of Echoes & Reflections. Ariel received her undergraduate degree in Religion Studies at Lehigh University with a focus on Holocaust history and education and sat on the committee to choose the first Holocaust education chair at the university. Ariel lives in New Jersey with her husband Adam, her two daughters Sadie and Olivia, and two puppies Moana and Zeus.

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

TEACHING

UNCATEGORIZED

The Kristallnacht Pogrom marked a devastating turning point during the  Holocaust: a shift from antisemitic propaganda and policy to government-sanctioned violence against Jewish communities in Germany, annexed Austria, and in areas of Czechoslovakia that had been recently occupied by German troops. The anniversary of this event on November 9 and 10 presents an opportunity for educators to explore this history with students—to teach about the dangers of antisemitism and the role and responsibility of an individual in interrupting the escalation of hate. Furthermore, the lessons of the Kristallnacht Pogrom, only further highlight the importance of our collective duty to uphold the pillars of democracy. At a time when our nation is facing increasingly high levels of antisemitism, the lessons from the “Night of Broken Glass” can resonate deeply with students and compel them to examine the critical need to stand up to antisemitism and all forms of hate. Here are some strategies and resources to guide you in teaching this topic:

Holocaust: a shift from antisemitic propaganda and policy to government-sanctioned violence against Jewish communities in Germany, annexed Austria, and in areas of Czechoslovakia that had been recently occupied by German troops. The anniversary of this event on November 9 and 10 presents an opportunity for educators to explore this history with students—to teach about the dangers of antisemitism and the role and responsibility of an individual in interrupting the escalation of hate. Furthermore, the lessons of the Kristallnacht Pogrom, only further highlight the importance of our collective duty to uphold the pillars of democracy. At a time when our nation is facing increasingly high levels of antisemitism, the lessons from the “Night of Broken Glass” can resonate deeply with students and compel them to examine the critical need to stand up to antisemitism and all forms of hate. Here are some strategies and resources to guide you in teaching this topic:

Explore Personal Narratives

Those who experienced the horrors of the Kristallnacht Pogrom provide powerful insights into the impact of the choices and decisions made in the face of the growing hatred and violence that surrounded them. As a teenager, Holocaust survivor Kurt Messerschmidt witnessed mobs attacking Jews in the street, in their homes, and at their places of worship, while many of his German neighbors and friends stood idly by. His testimony offers an important and inspirational message for students:

“SOME OF THE PEOPLE DISAPPROVED, BUT THEIR DISAPPROVAL WAS ONLY SILENCE.”

Have students reflect on this powerful statement and learn more about Kurt Messerchmidt:

- Watch Kurt’s video testimony clip to examine the ramifications of remaining silent in the face of hate.

- Engage students with USC Shoah Foundation’s IWitness activity about Kurt to learn more about his experience during the Holocaust.

- Download our Inspiring the Human Story poster series and accompanying activities, featuring Kurt and other important figures from the Holocaust.

Additionally, the testimony of survivor Esther Clifford, also impacted by the devastation of the Kristallnacht Pogrom, can help students understand the human story behind this event and consider the consequences of not standing up to injustice.

Use Primary Sources

A key component of our Echoes & Reflections pedagogy is to enrich students’ understanding of the Holocaust by providing an abundance of print and digital resources from a variety of perspectives. An examination of historical documentation can aid students to further contextualize and gain a deeper understanding of the Kristallnacht Pogrom:

- Access our lesson plan, Kristallnacht: “Night of Broken Glass”, and Unit on Nazi Germany for tools and approaches for incorporating primary sources into your instruction.

- Read our blog written by an Echoes & Reflections teacher who offers suggestions for using primary sources to connect students to the lessons of the Kristallnacht Pogrom.

- Take a virtual field trip with students to Yad Vashem - The World Holocaust Remembrance Center to explore primary sources from the Kristallnacht Pogrom featured in their online exhibition.

Teach with a Timeline:

Timelines can serve as a visual tool for studying periods of history and help students realize not only how events happened, but how to construct meaning and illuminate the human experience throughout a past era. This resource can also encourage students to see connections between events occurring in a single period and bring history to life by mapping dates onto a cohesive narrative. On our interactive Timeline of the Holocaust with accompanying activities, teachers can introduce the Kristallnacht Pogrom, as well as the dates prior to and immediately following this pivotal incident, which can allow students to grasp that the Holocaust was a progression of decisions, actions, and inactions, any of which might have happened differently if alternative choices were made.

Teaching about the Kristallnacht Pogrom is a crucial component of Holocaust education as it can reinforce students’ understanding of what ultimately led to the extermination of Europe’s six million Jews by the Nazis, underscoring the notion that the Holocaust was not inevitable.

CURRENT EVENTS

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

...feels different this year. As we prepare to honor Holocaust Remembrance Day (beginning the evening of April 20 through sundown on April 21) an unprecedented global health crisis unfolds. In many ways, tragedies can bring out the best in humanity. However, historically, such crises can also lead to an increase in scapegoating, xenophobia, and hurtful or damaging rhetoric. Today, as COVID-19 continues to affect us all, ADL has documented a rise in these behaviors, specifically against Jewish and Asian American and Pacific Islander communities in the U.S. Teaching about the dangers of unchecked hate and antisemitism, both past and present, remains paramount.

Yet, in these dark times we are hopeful. We believe that one of the most effective ways to combat antisemitism and other forms of hate is through a deep understanding of the history behind these harmful attitudes and how they continue to influence our world today. Yom HaShoah, a call for remembrance, presents a meaningful opportunity for educators to help their students reflect on the past in order to build a positive and peaceful present and future. And, although you may not be in your regular classroom or have the ability to physically make a school trip to a memorial or museum, you can still honor this day and positively impact students with lessons from the Holocaust.

How can we remember the victims of the Holocaust during this turbulent time?

Teach the Human Story

Teaching the human story of the Holocaust is one of Echoes & Reflections key pedagogical principles, as it can have a profound impact on students’ connection to this event. Fostering empathy through personal stories is especially essential during this unsettling period of uncertainty and separation. We encourage educators to commemorate this upcoming day of remembrance by sharing visual history testimony from Holocaust survivors and witnesses with students, all of which are found in our lesson plans. Each testimony is accompanied by guiding questions to support student reflection and comprehension. The testimony of survivor Henry Oertelt in our Contemporary Antisemitism Unit is particularly powerful, as he states:

"I am the prime example of what can happen when no one speaks up against prejudice."

Poignant words like Henry’s help students understand the importance of being an ally and work to make the world a better place.

Human stories are not only found in visual history testimony, but can also be accessed through works of poetry, art, photographs, and other artifacts from the Holocaust, also found in our lesson plans. These primary sources act as powerful tools to enrich students’ understanding of this history and can compel them to make change.

Engage with The Power of Community

Many of our friends at local Holocaust Museums and Centers, who would normally host in-person commemorative events for Yom HaShoah, have shifted to online ceremonies. We encourage you and your students to connect with others by participating in virtual commemorations offered by these institutions in your area. Additionally, we invite you to join our Partner Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center's live broadcast marking the start of Holocaust Remembrance Day on 4/20 as well as their virtual name-reading campaign on 4/21 to record the name reading of a Holocaust victim and share the video on social media.

Even during this deeply difficult time, we still have the power to work towards change and connect with our communities. On Yom HaShoah, by looking towards the past we can support our youth to examine the present and build a more secure and peaceful future. Through remembrance we can inspire positive action.

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

TEACHING

Idaho social studies educator Ben Harris suggests, “The Idaho Anne Frank Human Rights Memorial doesn't seem to be a place of commemoration or sadness – what one might experience in a battlefield or concentration camp. Instead, it invites students to consider a variety of perspectives about human rights and ask questions.”

A study by the Pew Research Center released in January 2020 found that visiting a Holocaust museum or memorial is strongly linked with Holocaust knowledge. A visit to a museum or memorial takes Holocaust education out of the classroom, while encouraging learning approaches and outcomes that are central to Echoes & Reflections pedagogy: inquiry-based learning and critical thinking, fostering empathy, and making the history relevant for students. These visits help students develop a personal connection to the Holocaust.

“Dear Kitty … No one is spared. The sick, the elderly, children, babies and pregnant women – all are marched to their death. I get frightened myself when I think of close friends who are now at the mercy of the cruelest monsters ever to stalk the earth. And all because they’re Jews.” - Anne M. Frank, November 19, 1942

Etched in the stone of the Idaho Anne Frank Human Rights Memorial in Boise, Anne’s diary entry illustrates how a group of people who are marginalized or demeaned based on religion, race, ability, gender, sexual orientation or gender identity become viewed by a majority as “the other” and therefore less than or inferior. It’s a stark reminder of what can happen when we fail to interrupt the Spiral of Injustice, a model we created for discussing the Holocaust, the attack or harassment of an Idaho student when he or she is viewed as “the other,” or the marginalization of any group within the fabric of our community.

The Wassmuth Center was founded in 1996 for the purpose of constructing a memorial to human rights. That vision became a reality when the Idaho Anne Frank Human Rights Memorial opened to the public in 2002. Inspired by Anne Frank and funded through the generosity of individual and corporate donors, the Memorial is not simply a static space to reflect on her short life or even on the horrors of the Holocaust. Instead, it was designed to actively engage visitors to think, to talk with one another, and to respond to the human rights issues we face in our community, our country and our world.

Both the triumphs and tragedies of the human story are on display but, in every quote and every idea, visitors see the profound power of a single voice or bold action to overcome great odds and alter the course of history.

The educational park includes: a life-sized bronze statue of Anne Frank as she peers out an open window into an adjoining amphitheater, 80 quotes  etched into the stone throughout the Memorial, the full text of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on permanent display, the Rose Beal Legacy Garden honoring a local Holocaust survivor, a sapling from the Anne Frank Chestnut Tree in Amsterdam, the Marilyn Shuler Classroom for Human Rights, recognizing a founder of the Memorial and the state’s first director of the Human Rights Commission, and state-of-the-art electronic technology showcasing the “History of Human Rights in Idaho.”

etched into the stone throughout the Memorial, the full text of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on permanent display, the Rose Beal Legacy Garden honoring a local Holocaust survivor, a sapling from the Anne Frank Chestnut Tree in Amsterdam, the Marilyn Shuler Classroom for Human Rights, recognizing a founder of the Memorial and the state’s first director of the Human Rights Commission, and state-of-the-art electronic technology showcasing the “History of Human Rights in Idaho.”

Ryan Coonerty, in the National Geographic publication Etched in Stone: Enduring Words from our Nation’s Monuments, commented, “Anne Frank could scarcely have conceived of Boise, Idaho. Therefore, it seems improbable that the author of a diary that has become among the world’s most widely read books has become a symbolic fixture of this community almost 60 years after her death.”

The Memorial receives an average of 120,000 visitors annually, with over 10,000 K-12 and university undergraduate students participating in free docent-led tours.

How does a visit to the Memorial inspire and impact teaching and learning about the Holocaust?

A visit to the Idaho Anne Frank Human Rights Memorial is far more than a fieldtrip and can provide a strong foundation for when educators return to the classroom and continue to teach the lessons of the Holocaust and other genocides. It is the recognition, as stated by Edmund Burke, “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men [and women] do nothing.”

Consider and ask. When visiting a memorial or museum, the site can introduce a different perspective and an opportunity to ask probing questions.

We see that happen on tours when either a classroom educator or Memorial docent asks each participant to select his/her favorite quote in the Memorial. The process of selection includes both introspection and reflection; do I see myself in the quote and what does it mean to me? As students begin to share their selections, the conversation becomes a moment of personal journeys.

High school English teacher Sharon Hansen adds, “While the quotes are available in a booklet or in a digital version, we choose to visit the site, where we feel the presence of Anne Frank looking out over us as we write-- she forever frozen in her hiding place, while those of us who are alive and free have an opportunity to write about injustice in order to move toward justice.”

Power of place. At the entrance to the Memorial, visitors read a welcome written by one the Memorial’s three founding mothers Rev. Dr. Nancy Taylor. “May the Idaho Anne Frank Human Rights Memorial stand as a tribute to Anne Frank’s memory, as a warning to any who would dare trespass upon the freedoms of others, and as an inspiration to all whose lives are devoted to love, respect, understanding, peace, and good will among the totality and diversity of the human family. May this memorial inspire each of us to contemplate the moral implications of our civic responsibilities.”

Visitors experience the place – it is a physical, emotional, and some might add, a spiritual experience that evokes connections.

Hansen shares, “For my Creative Writing students, a visit to the Memorial is a call to action. Their writing takes on new purpose, one determined by the place, and one I cannot duplicate in the classroom. The Anne Frank Memorial is a place of inspiration, calling forth the words of my students to amplify the Memorial’s message.”

Behind the statue of Anne Frank, the actual size of the family rooms in the secret annex is cut into the concrete; one point of access into the rooms is  up a nine-step staircase tucked behind a marble bookcase, and the surrounding walls mirror the Amsterdam skyline.

up a nine-step staircase tucked behind a marble bookcase, and the surrounding walls mirror the Amsterdam skyline.

Memorial visitors are able to step into her diary. And we point to a quote by the American journalist Judith Miller that sits adjacent to the Memorial’s entrance. “We must remind ourselves that the Holocaust was not six million. It was one, plus one, plus one …” Anne Frank was one, her sister Margot was one, their mother Edith was one …

Never Again, Never Forget. We recite it, we mean it – but genocide continues to happen. Notably, George Santayana’s words are also inscribed in the Memorial. “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

In addition to the Holocaust, we talk about the Armenian, Cambodian, Ukrainian, Rwandan and Bosnian Genocides. Students are apt to point out that “never again” rings hollow. Another quote, placed on a rock by the family of a Holocaust survivor, insists, “Never again is now.”

Recognized as a member in the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, the Memorial joins a network of historic sites, museums and memory initiatives that connects past struggles to today’s movements for human rights. The Idaho Anne Frank Human Rights Memorial commits to turning memory into action.

Hansen notes, “The Boise River flows along the Memorial, perhaps echoing the words of Martin Luther King Jr. ‘Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.’ By being present at the Memorial, students are surrounded by the words of Haim Ginott, Sojourner Truth, and Nelson Mandela, and the language becomes a springboard for students’ own yearning toward a free and just future.”

And “in spite of everything” Anne still believed that “people are truly good at heart.”

About the author: Dan Prinzing, Executive Director of the Wassmuth Center for Human Rights in Boise, Idaho, has a BA in History Secondary Education, an MA in Curriculum and Instruction, an MA in History and Government, and a Ph.D. in Educational Administration. Prior to the current position, he was the Idaho State Department of Education’s coordinator of civic and international education, the former SDE coordinator of social studies and curricular materials, and a language arts and history teacher in the Boise School District.

To learn more about the Anne Frank please explore our additional resources on her life and legacy:

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

TEACHING

On January 27th, the anniversary of the allied liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, we commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day in honor of the victims of Nazi persecution. This annual observance provides an opportunity for teachers to focus on the pivotal role of liberators in defeating the Nazis at the culmination of World War II, and as some of the first to bear witness to the horrors of the Holocaust. Here are some strategies and resources to guide you in teaching about this topic:

Teach the Human Story: Survivor and Liberator Testimony

Eyewitness testimony highlights the human story behind the Holocaust and can help students further understand the importance of preserving one’s humanity during this dark period in history. Hearing from survivors on the paradoxical joy of liberation and darkness of facing a return to life without family, as well as from American soldiers who saw firsthand the horror of Nazi atrocities, offers an excellent entry point to the study of the Holocaust. Explore below:

Survivors

- Dennis Urstein: Born on February 24, 1924, in Vienna, Austria, he was incarcerated in the Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen, Ohrdruf, Auschwitz I, Mechelen, and Dachau concentration camps, and in Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp.

- Henry Mikols: Born on August 27, 1925, in Poznan, Poland. As a political prisoner, Henry was incarcerated in the Ellrich and Buchenwald concentration camps. From Buchenwald, Henry was sent on a death train to Bremen and then on to Bergen-Belsen, where he was eventually liberated.

- Ester Fiszgop: Born on January 14, 1929, in Brzesc nad Bugiem, Poland. She was forced to live in the Drohiczyn ghetto and later went into hiding in various places, including barns, forests, and attics.

Liberators

- Howard Cwick: Born on August 25,1923, in New York, NY. As a member of the United States Armed Forces, he, along with his fellow soldiers, liberated the Buchenwald concentration camp.

- Anton Mason: Born on April 19, 1927, in Sighet, Romania. He was forced to live in the Sighet ghetto and was later imprisoned in the Buchenwald, Gleiwitz, Auschwitz, Auschwitz I, and Auschwitz III-Monowitz concentration camps, as well as Auschwitz-Birkenau.

- Paul Parks: Born on May 7,1923, in Indianapolis, IN. As a member of the United States Armed Forces, he, along with his fellow soldiers, liberated the Dachau concentration camp.

In addition to oral testimony, written testimony is also a useful way to engage students in the human story of the Holocaust:

Our blog by Sheryl Ochayon, Echoes & Reflections Project Director at Yad Vashem, offers reflections on her interview with WWII liberator Alan Moskin and the importance of Holocaust remembrance.

You can also share written testimony from liberator Harry J. Herder, Jr., who was nineteen at the time he and other US soldiers liberated Buchenwald, in April 1945.

Teach through the Medium of Film

Explore our Video Toolbox, Liberators and Survivors: First Moments, on the liberation of concentration camps by the US Army at the end of WWII. This short film interweaves liberators’ and Jewish survivors’ testimonies and other primary sources, helping you present their personal stories to your students. Watch here

Engage Students with Multimedia Activities

Through our Partner USC Shoah Foundation’s IWitness, we bring the human stories of the Holocaust to secondary school teachers and their students via engaging multimedia-learning activities on the topic of liberation:

- New Beginnings-Journey to America

- Information Quest: Howard Cwick

- Understanding Displaced Persons’ Camp

Suggested Questions to Engage Students

1. How do you think survivors felt after learning they were liberated? What do you imagine some of their fears were?

2. What obstacles did survivors have to overcome following liberation?

3. What do you imagine were some of the thoughts and feelings liberators had after their experiences liberating the camps?

4. What is the effect of hearing both survivors and liberators talk about liberation? What kind of information do you learn from each?

5. What kind of information does the survivor provide that would be impossible to learn any other way?

Looking for more?

Our Unit on Survivors and Liberators contains all the resources mentioned in this piece as well as additional learning tools for exploration.

Deepen students' learning of liberation by viewing significant dates in history on our interactive Timeline of the Holocaust resource:

ANTISEMITISM

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

We are clearly living in turbulent times. ADL regularly reports a rise in antisemitic incidents, both here and abroad, and the proliferation of right- wing populist governments continues to be cause for concern. And against the backdrop of increasingly partisan rhetoric in this country as elsewhere, it is incumbent upon teachers to educate our students about the Holocaust and to show them what happens when hateful racist ideology takes hold of governments and even entire societies until only widescale force applied can bring an end to the madness.

At such a moment, it is sobering to teach about Kristallnacht because, in retrospect, we can clearly see the two-day pogrom as a watershed moment, a three-week period when physical attacks upon Jewish lives and property in Nazi Germany were front page news in this country. But, when international outrage and condemnation resulted in no real consequence to the German State, the Nazi leadership interpreted this inaction as a green light to pursue their anti-Jewish agenda.

To those of us aware of this history, the need to push back against antisemitic, racist, homophobic, and or misogynistic rhetoric and policy is fueled both by moral outrage and by the need to protect against an analogous tipping point in our own times.

It wasn’t long after I started teaching Holocaust literature that I found Echoes & Reflections, or rather Echoes & Reflections found me. I attended several of their workshops and seminars at the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center, and I immediately gravitated to their philosophical approach to the subject matter and to their focus on the individual story. Among their many lesson plans is one about the November Pogrom.

The facts of November 9 and 10, 1938, are well known. “From the time the Nazis came to power in 1933 they began isolating Jews in Germany, and passed many laws to that effect. In the first half of 1938, additional laws were passed in Germany restricting German economic activity and educational opportunities…Later that year, 17,000 Jews of Polish citizenship were arrested and relocated across the Polish border. The Polish government refused to admit them so they were interned in relocation camps on the Polish frontier.”[1] Among the many deportees were the parents of seventeen-year-old Herschel Grynszpan, who was living with an uncle in Paris at the time. Outraged by the Nazis’ treatment of his family, he went to the German Embassy in Paris intending to assassinate the German ambassador there but instead killed Ernst vom Rath, a lesser figure in the diplomatic hierarchy. When vom Rath died two days later from his wounds, the Nazis used his death as a pretext to launch attacks on Jewish synagogues, homes, and businesses throughout Germany.

What is interesting and significant about these events from a teaching perspective, is that we have documents related to the attack which make it perfectly clear to our students that the Nazis planned every aspect of the events over that two- day period. For example, Echoes & Reflections materials include a copy of Heydrich’s Instructions to “All Headquarters and Stations of the State Police and “All districts and sub districts of the SD (the Sicherheitsdienst or Secret Police).”[2] Asking students to examine this document and report their findings to their peers allows them to see for themselves the extent of Nazi cynicism and corruption with respect to the rule of law and of human decency. For example, the police were instructed that “only such measures are to be taken as do not endanger German lives or property (i.e. synagogues are to be burned down only where there is no danger of fire in neighboring buildings).”[3]

As a teacher, I find it imperative that students be guided to discover the truths of these documents for themselves by way of careful questions. For example, you can ask them what instructions they would give to their district commanders were they the officers in charge of managing a demonstration in their home city or community. More poignantly, you can ask them what they think Heydrich is saying when he draws a distinction between German and Jewish property. Finally, you can ask them to think about the international situation in 1938 and the reason Heydrich cautions that “Foreign citizens, even if they are Jews, are not to be touched.”[4]

It is both exhilarating and sobering to teach this material to young people. Hearing their outrage and their determination to never let this happen again gives one hope for a better world. And yet, it is sobering to lead these students inevitably towards the later events of the Holocaust and towards the realization that fellow human beings are capable of such atrocities.

This summer I spent three weeks immersed in Holocaust studies in Israel at Yad Vashem. I now know more about the events of the Nazi era than ever before and paradoxically, the more I know about those years and those events, the harder it becomes to teach this history. It breaks my heart to have to tell these wonderful young people how ugly the human heart can be.

And yet, even the student who most hated to hear what happened, wrote of the Holocaust unit last year that he “needed to hear it” and that “only by learning this can we make sure such things can never happen again.”

At the end of this year’s lesson on Kristallnacht, I gave my students a new homework assignment. I asked them three questions about those events:

- Does it make a difference how we label those events, calling them either Kristallnacht or The November Pogrom?

- In what way(s) is your answer complicated by the fact the Nazis called it Kristallnacht and the Jews called it the November Pogrom?

- Who has the right to label the event: the perpetrators; the victims; or a third party such as a historian?

With few exceptions, my students are able to discuss the importance of the name and to connect the events of November 1938 to the long history of antisemitism that continues to this day. Their outrage gives me hope that teaching a rigorous Holocaust program in schools may help build a bulwark against the tide of hateful rhetoric permeating so much of the world today.

About the author: Originally from London, England, Dr. Susan Schinleber taught Cultural and Business and Communication at New York University before moving to Chicago with her young family. After teaching in several area universities, she moved to North Shore Country Day School in Winnetka, IL, where she teaches English, Public Speaking, and Holocaust Studies.

[1] Excerpt from Studying the Holocaust, Kristallnacht. Echoes & Reflections.

[2] From Heydrich’s Instructions, November 1938 in Studying the Holocaust, Kristallnacht. Echoes & Reflections.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

SURVIVORS

"In two years of combat you can imagine I have seen a lot of death […] but nothing has ever stirred me as much as this […] how could people do things like that? I never believed they could, until now."

- US Staff Sergeant Horace Evers, among the liberators of Dachau, from a letter home featured in Echoes & Reflections

The liberators of the Nazi camps were young soldiers — many no older than 18 or 19 years old. They were the first outside witnesses to come face to face with the evidence of the monstrous crimes committed by the Nazis and their collaborators against civilians.

Their testimony is qualitatively different from that of survivors of the Holocaust. They had seen their buddies killed in war – they were all too familiar with death and destruction. But the scenes they saw as they liberated the camps were unlike their military experiences. They were suddenly and unexpectedly forced to become witnesses to horrific atrocities. This was a different kind of trauma. Their reactions ranged from shock to disgust to rage. Their “why remember?” comes from this place and this witnessing.

In November, I had the privilege of hearing Alan Moskin speak. Mr. Moskin was part of General George Patton’s Third Army. He fought in the Rhineland campaign through France, Germany and Austria. When the Nazis surrendered he was not yet 19. When I heard him speak he was 92 years old, yet the memories were still fresh. He liberated Gunskirchen, a subcamp of Mauthausen, on May 4, 1945.

Mr. Moskin spoke quietly of the overpowering stench and the thousands of corpses and the barbed wire, as though he could still see them. He spoke with great compassion for the skeletal survivors (the “poor souls”, as he called them) who were so hungry that they ate the tobacco from the cigarettes the soldiers gave them; who were so thankful that they tried to kiss his boots though they were caked with blood and feces; who were so covered with lice and filth and open sores that they literally reeked. He remembered his captain screaming into a walkie-talkie, “Get help up here, GET HELP!” He remembered feeling weak in the knees and, overcome with emotion, crying.

Mr. Moskin spoke in memory of the 6 million murdered Jews and the others who were persecuted. He also paid tribute to “his own band of brothers” who, as he said, made the ultimate sacrifice. He purposely, purposefully recited each of their names, rapping on a table for emphasis with every name he pronounced: Tex, Jimbo, Muzzy, RJ, Bulldog, Schoolboy, LZ, Rebel, Gonzo, Tony C., Tommy, who was blown to pieces by a mortar shell right before his eyes, and Captain B., the captain he loved, who jumped on a live grenade to protect his squad.

Alan Moskin’s was a different kind of testimony than those I’ve heard from Holocaust survivors. But even if his “why remember?” comes from a different place and a different experience, its goal is the same: not to let any of this be forgotten, “for the sake of humanity and everything decent and just in the world.”

I repeat his words here because they made a profound impression on me. They came from his heart.

“I speak here today for each one of those poor souls who was slaughtered by the Nazis, and each one of my buddies and all the other GIs who made the ultimate sacrifice. They can’t speak anymore but dammit I can and I will. I’ll speak out as long as God gives me the strength to do so. I feel that I’m their messenger. The message is that there was a Holocaust. I bear witness. It occurred. I saw it. I want these young people that I speak to, to be my witness. I don’t want them to forget. There are deniers out there now and when we’re gone who knows what they’re gonna say. That the Jews made it up? That it didn’t happen? Well it did happen. And I want these young people to bear witness for me. It’s been said many times that those who forget the events of the past are doomed to repeat them.”

International Holocaust Remembrance Day is commemorated on January 27th, the date in 1945 on which Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest Nazi concentration and death camp, was liberated. The UN tied commemoration of the Holocaust to this important milestone of liberation. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon stated in 2008 that the essence of this Remembrance Day is a twofold approach: one that deals with the memory and remembrance of those who were massacred during the Holocaust, and the other that goes beyond remembrance to educate future generations of its horrors.

This is exactly the “why remember?” message of Alan Moskin’s testimony and that of other liberators like the ones featured in the Echoes & Reflections toolbox film, “Liberators and Survivors: The First Moments.” There are still liberators among us. We must listen to their stories and share them with our classrooms and communities while we still have the chance to hear them.

About the Author: Sheryl Ochayon is the Project Director for Echoes & Reflections at Yad Vashem.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

As the commemoration of the 80th anniversary of Kristallnacht approaches, I am drawn to the words of Holocaust survivor Kurt Messerchmidt: “Silence is what did the harm.” I can’t help but consider the relevance of this statement and Kurt's experiences during the Holocaust to the lives of my students. The anniversary of Kristallnacht, as well as my recent experiences in Holocaust education, provide a powerful teaching opportunity to examine the importance of recognizing personal narratives as well as the consequences of staying silent in the face of injustice.

This summer, through Echoes & Reflections—a partnership of ADL, USC Shoah Foundation, and Yad Vashem—I had the opportunity to travel to Poland with an incredible group of dedicated educators from across the United States and our guide, Sheryl Ochayon, the Program Director for Echoes & Reflections at Yad Vashem. To say that it was an impactful experience doesn’t begin to encapsulate the enormity of what we learned and what we were able to bring back to our classrooms.

I am an educator at The Newcomer Center in Arlington Heights, Illinois and work with immigrant and refugee students that are newly arrived to the United States. My Newcomer students, many of whom have suffered trauma in their countries of origin, connect on a deep level with the study of the Holocaust. The fear and constant threat of violence, hiding to survive, the sense of displacement, and the loss of “home” are some of the things my students have already experienced in their short lives.

The trip to Poland—standing on seemingly forgotten historic grounds where violent pogroms occurred, walking through the deafening silence of concentration camps, and touring museums full of exhibits of what used to be Jewish life—provided me with a fresh perspective on an otherwise familiar topic. It was a reminder to find the individual stories in the lives of the more than six million victims of the Holocaust, and to remember that every single person, one-by-one, added up to six million. It was a reminder to teach my students that the six million are not a singular collective story of loss and by recognizing individual lives, cut short by cruelty and hate, is how we restore their humanity and work to ensure that future acts of hate cease to occur.

Every Newcomer student is a single story. Each student carries his or her own hurt, loss, and suffering. At times, unintentionally, and under the weight of the monumental task of preparing my students for new lives in the United States, I’ve exercised a version of “silence” by failing to recognize their pain. Without knowing it, I stopped hearing their voices.

I hope to always acknowledge my students and their plights as individual stories of resilience and hope. This is what I brought back with me from Poland. A fresh way of being an advocate for my students and a reminder to find the one in the six million. As educators, it is as important today as it ever was, to take every student into account and to help them find their voice. In the end, it is the silence that continues to do the most harm.

About the author: Mario Perez is the Coordinator and Social Science/Human Geography Teacher at the Newcomer Center in Arlington Heights, IL, a lifelong Chicagoan, and proud educator for over 18 years working with immigrants and refugees as they start their new lives in the United States.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

UNCATEGORIZED

I knew spending a week studying the Holocaust would be an intense undertaking. What I didn’t realize is that spending a week bearing witness at the sites of these atrocities would also be heartbreaking. And while my experience on Echoes & Reflections Educational Journey through Poland with Yad Vashem was both of these things, it was also enlightening and empowering. We all left a piece of ourselves in Poland, but took away so much more.

Holocaust education has always been a passion of mine. Something about the resilience of the Jewish people, the ability to have seen so much hatred, but still stand strong inspires me. I have participated in numerous professional development programs on the subject. I have also been lucky enough to spend two summers as part of the Charlotte and Jacques Wolf Conference with ADL, which allowed me to convene with other experienced Holocaust educators from around the country for a multi-day in-depth exploration of Echoes & Reflections materials. I have always left these experiences with a renewed mission and a stronger commitment to my students to educate them on the important lessons of the Holocaust, which often includes telling the stories that are difficult to hear. When I saw the opportunity to further my studies and my understanding of the Holocaust with a group of educators who are equally as passionate as I am, I jumped at the opportunity to visit Poland. I have always told my students that my voice cannot do justice to the stories of this time period. I was not there, I did not live it, and I never stood where the victims and survivors stood, so how could I truly understand? It was my hope that in taking part in this journey that I would be able to do just that—to give voice and do justice to those who lost their lives.

As our group came together, we discovered we were all on this trip for different reasons. Yet, we all had one thing in common: we were all there to bear witness. To say, “I have seen. I will not forget.” Every day was harder than the one before. Every day we would feel both depleted and fulfilled. Every night we would question whether we could see any more, feel any more. It is something special to allow yourself to be vulnerable with a group of strangers. But through this journey, we became something more. Sharing in this experience has changed all of us—it has left its mark on our hearts.

Our week in Poland was heavy and it would have been easy to be pulled into a spiral of depression. In our five days, we visited extermination camps, sites of mass graves, and heard the stories of death and destruction as we stood within the ghetto walls. But throughout these visits, we also heard stories that filled us with hope. We heard stories of resistance—people who fought back in any way that they could. We heard stories of love, of friendship, of family. Through these stories, we began to see not the nameless faces of the victims, as the Nazis intended, but the individuals. One of the most powerful moments during the trip was when we each presented on a person that we were asked to research. When we arrived to a site that connected with our person, we shared about their life.

I was asked to research Mordechai Anielewicz. Mordechai was a leader in the Jewish Fighting Organization (ZOB) and was instrumental in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and inspiring and leading the Jewish people to fight back against the Nazis. As I was researching and sharing his life, I was struck by how incredibly young he was during these events. I always talk to my students about how their voice matters and Anielwicz’s story further confirmed my belief that today’s youth have the power to inspire change. I viewed testimony where a survivor remembers being introduced to Anielewicz as “Mr.”, even though he was only about 20 years old. It didn’t matter to his people how young he was, what mattered was his passion and his belief in what he was asking of his people. I was also struck by Mordechai’s willingness to give his life for his cause. In his final letter, he writes “The dream of my life has risen to become fact. Self-defense in the ghetto will have been a reality.” As I stood at the site of the bunker where Mordechai took his final breaths, I was overwhelmed by his bravery and self-sacrifice in the face of evil. As we shared stories of bravery, resistance, and love , these victims have marked our hearts and we will never forget their names. We will remember them. We will be their voice.

I believe in “never again.” I believe if we show our students and teach them about the atrocities of the past, we can make a better future. This trip strengthened this belief and emphasized the importance of what we do every day as educators. Every voice matters. It is our job as educators to help our students find their own. It is our responsibility to ensure that our students have open eyes and open hearts, using the stories of the past to shape our future.

About the Author: Ashley Harbel is an English teacher at Sanborn Regional High School in Kingston, NH.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

Wrote T.S. Eliot in “The Burial of the Dead,” the first section of The Waste Land. That line could not have been about April 19, 1943, when Jews in the Warsaw ghetto took up arms to resist Nazi soldiers who had come to deport them to concentration and extermination camps. Nor could it have been about April 7, 1994, when the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda began. The Waste Land was published in 1922. But, by some sort of irony, Yom Hashoah, or Holocaust Remembrance Day, is often in April, as is the case this year. Also, the commemoration of the genocide against the Tutsi begins on April 7.

On April 7, 1994, all of my wife’s relatives who lived on a hill called Kunanga, a total of 118 of four generations, were killed. Among the victims were my two aunts, Nyirabagenera and Kamamure, who were married to my wife’s cousins. What happened on that hill on that fateful day was also happening on several other hills and in several valleys across the mountainous country, and would continue to happen in the following 99 days. By July 4, when soldiers of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) took control of the entire country, ending the genocide, over a million Tutsis and their Hutu sympathizers had been killed. As a kid in 1959, I had seen houses go up in flames; unbeknown to me then was that the houses were torched because they belonged to Tutsis. Thirty-five years later when the genocide was carried out, I was living and teaching in Zimbabwe. Although I knew then of the many anti-Tutsi pogroms, I was not prepared for the incessant news of indiscriminate killings of Tutsis —the old, the young, the infant, and even the unborn. The news, though numbing, gave rise to a hatred for Hutus who had killed innocent beings just for who they were. They must have been monsters, I erroneously thought. You see, I had no historical references whatsoever for what was happening in Rwanda. I had not read Karl’s confession to Simon Wiesenthal, author of The Sunflower, to understand how ordinary people become perpetrators. Karl, a dying Nazi soldier, had been raised Catholic and had joined Hitler’s Youth and the SS, institutions in which he had been taught that doing what he was commissioned to do was a patriotic duty. Granted, I knew that approximately six million Jews had been killed during the Second World War, but I did not know why or how they had been killed. The Holocaust had never been part of my curriculum.

That was to change 14 years later when I had opportunities to learn about the Holocaust, which to me was an entry into learning about the genocide against the Tutsi. These opportunities included a seminar on Holocaust education at The Olga Lengyel Institute for Holocaust Studies and Human Rights (TOLI) in 2008; an Echoes & Reflections seminar at Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Centerin 2011; a TOLI educational tour of Poland’s Holocaust sites and Israel’s historical sites in 2012. From these educational opportunities, I learned two fundamental lessons: one, that all genocides have histories; two, that genocide is preventable. Irving Roth, a Holocaust survivor who spoke at the 2008 TOLI Summer Seminar I attended, used the term “signposts” along the road to the Holocaust to underscore the fact that the Holocaust was not a spontaneous event: there had been the Nuremberg race laws, which codified policies of discrimination against Jews; the Kristallnacht Pogrom, when several synagogues and Jewish-owned businesses were destroyed; the letter “J” on Jewish identity cards, which made it possible for Nazis to single out Jews for any nefarious purposes.

The road to the genocide against the Tutsi too, like all roads leading to genocides, had signposts. Using criteria of scientific racism, the Belgian colonial administration had noses of individuals in Rwanda measured to determine who was Hutu and who was Tutsi. Gerard Prunier in The Rwanda Crisis quotes a colonial administration document which described Tutsis as having “features [that] are very fine: a high brow, thin nose and fine lips” and as being “gifted with a vivacious intelligence”; Hutus as being “short and thick-set with a big head” and “less intelligent”; and Twas as having “a monkey-like face.” The administration also issued identity cards with Tutsi, Hutu, and Twa labels, and enacted policies that favored Tutsis and discriminated against Hutus and Twas. For example, it removed Hutu chiefs and replaced them with Tutsis. In the late 1950s, when the Tutsi elite demanded political independence from Belgium, the colonial administration switched its allegiance to the Hutu. In 1959, rumors of an attack of a prominent Hutu leader by a group of Tutsi young men sparked the first anti-Tutsi pogrom. In 1962, following Rwanda’s independence, the exclusively Hutu government continued the policy of issuing identity cards with Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa labels in order to enforce discriminatory policies against Tutsis. For example, teachers were mandated to regularly do a headcount of Tutsi students in their classes so as not to exceed the allowed quota. In her memoir, Chosen to Die, Destined to Live, Frida Gashumba wrote, “The head count of Hutus and Tutsis came to be a three-month occurrence, as the headmaster complied with the government’s directive…. Each time the Hutu children would laugh at us and goad us, and neither the headmaster nor our teacher would make any attempt to shut them up.” The Hutu government also oversaw anti-Tutsi pogroms in 1963, 1967, 1973 when all Tutsi students were expelled from the only university in the country then, and 1990. Perhaps worst of all signposts on the road to the genocide was the dehumanization of Tutsis; they were called cockroaches, rats, and snakes, which justified their extermination.

In On Austrian Soil, one of the texts we used at the 2008 TOLI Summer Seminar, Sondra Perl wrote: “You are not responsible for the past. But I think you do have, that we all have, a responsibility to the future.... Not to turn our backs. Not to be silent [in the face of any form of social injustice].” Perl’s primary audience was educators, who have the responsibility to teach against prejudice, discrimination, and persecution—beliefs and practices that potentially lead to genocide. That ordinary people in Germany and in Rwanda became genocide perpetrators indeed speaks to the failures of institutions, such as schools, which taught or tolerated prejudice and hatred. This April month we remember the Holocaust, the genocide against the Tutsi, and other genocides to recall mistakes of the past so that they are not repeated.

About the Author: Gatsinzi Basaninyenzi, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of English at Alabama A&M University.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

- Howard Cwick, on liberating Buchenwald concentration camp, from the Survivors and Liberators unit

Seventy-three years ago, on January 27, 1945, the concentration and extermination camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau was liberated by the Soviet army. While other camps were liberated by the Allies both before and after this date, it was the liberation of Auschwitz, perhaps the most potent symbol of evil in our time, that was chosen by the United Nations to be the date for an annual commemoration of the Holocaust.

In the preamble to its resolution creating International Holocaust Remembrance Day, the UN General Assembly specifically chose to honor “the courage and dedication shown by the soldiers who liberated the concentration camps...”

This year, to commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day, we at Echoes & Reflections have created a new resource which, likewise, shines a light on the liberators in those first unique moments after liberation. We are proud to unveil the latest film in our Video Toolbox: “Liberators and Survivors: The First Moments.”

“Liberators and Survivors” provides an entry point for US history teachers into the study of the Holocaust. The story of liberation is a powerful and natural bridge between the study of the military war itself, and the study of the genocide perpetrated against the Jews under the cover of that war. The film interweaves liberators’ testimonies with those of the Jewish survivors they liberated. It describes the intense emotional effect that seeing piles of lifeless bodies and half-dead survivors had on many young American soldiers, who questioned, “How can people do things like that?” It documents, with primary sources, the reaction of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who immediately understood the need for evidence to counter the distinct possibility that no one would believe the horrendous scenes of brutality the soldiers had witnessed. It discusses the compassion that many of the American liberators showed those they had liberated, attempting to provide care and suspending their military missions in order to do so. It also highlights those liberators who were moved to become a moral voice in later years, sharing their unforgettable stories and pleading that humanity learn from their experiences.

The survivors speak of the compassion shown by their liberators, and of their reaction to the American soldiers.

The film was specifically developed for use with students in the classroom. While most historical film footage of liberation contains disturbing visuals including mountains of corpses, we took great care not to include graphic visuals, making the film suitable even for middle school students. The film supports your teaching by opening with footage of WWII, and with a series of maps to illustrate the progress of the Allied armies. But it goes beyond the historical event of “liberation,” presenting the event through the personal stories of the soldiers who were eyewitnesses. It helps educators present this human story to students in order to venture out of the sphere of WWII and into the subject of the Holocaust.

Listening to the stories of the soldiers and survivors we meet in the film, and reflecting on their courage, compassion, and humanity gives real meaning to the purpose of International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Join us for webinars on January 22, 2018 and January 24, 2018 where we will discuss the stories of liberators and survivors.

About the Author: Sheryl Ochayon is the Project Director for Echoes & Reflections at Yad Vashem.

BYSTANDERS

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

LITERATURE

The day I began teaching eighth grade, I was handed a copy of Anne Frank, the Diary of a Young Girl. I was asked to teach it. The problem was…I had never read this book. It took me a few hours to get to know Anne, but once I did, I was hooked, but I also realized that the “it” I was being asked to teach came with an enormous responsibility. Where would I begin? How would I teach about the Holocaust in a way that had meaning for young teenagers?

I have been teaching Holocaust literature now for ten years. I have studied and become familiar with the resources available from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and Echoes & Reflections, which provide me with a sound pedagogy for teaching about the Holocaust. Still, given recent events that have rocketed the ideology of hate and intolerance onto the front page, I am once again struggling to find the path forward to incorporate the lessons of the Holocaust with the world my students are facing and the news that surrounds them.

As we prepare to remember the 79th anniversary of Kristallnacht, I find that the material from the Echoes & Reflections lesson, Kristallnacht: “Night of Broken Glass” in the Studying the Holocaust Unit provides me with an excellent entry point. In this lesson, Holocaust survivor Kurt Messerschmidt provides his first-person account of Kristallnacht. Although I am not a history teacher, I find his story compelling, and unfortunately, still timely. Kurt speaks of the silence he witnessed in response to that day and there is much to be learned from his testimony. Learning about Kristallnacht as a turning point in Holocaust history provides important context and offers an essential question we discover time and again in the Holocaust literature, “Would I have been a bystander, hiding behind silence?”

Unfortunately, my students see hate and the consequences of hate on television and in social media every day. When Kurt says, “Their disapproval [of Nazi actions] was only silence, and silence was what did the harm,” I challenge my students to consider if they are allies or silent bystanders in their own lives. We look at events, not only in the United States, but around the world, that are a result of hate and intolerance and consider appropriate actions.

My students and I explore a wide variety of Holocaust literature throughout my unit, and the students use the lesson about Kristallnacht and Mr. Messerschmidt as a year-long theme. We examine the results of inaction. What would those two Nazis at the cigar shop have done if the crowd of forty or fifty bystanders would have all started picking up the glass? I ask them to consider the ways that they can pick up the symbolic shards of glass that litter the landscape of our schools, communities, and beyond. We address silence in the context of World War II and the Holocaust, but I also show and discuss how it can be translated to current events. This year, I will also show the remarks of Holocaust survivor Sonia Klein to CNN after the events in Charlottesville, when she stated, "Silence is the first thing after hate that is dangerous because if you are silent, it is an approval of what's going on." I will show Sonia alongside Mr. Messerschmidt’s testimony to bridge the gap of decades between World War II and today.

This theme is also integrated into my advanced English classes when we read Elie Wiesel’s Night, and consider what Wiesel meant, when in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech he stated, “I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.” We also consider Anne Frank’s excruciating words when she wrote, "Sleep makes the silence and the terrible fear go by more quickly, helps pass the time, since it's impossible to kill.” At this point, silence has taken on a new meaning for my students. Anne Frank could not have been anything but silent, as she was in hiding, yet the power and bravery of her writing gave her a voice that continues to inspire millions.

Expanding on the theme this year, I will also implement the concept of “silence” into our poetry unit. The lyrics of the 1964 Simon and Garfunkel song “The Sound of Silence” will be introduced for student interpretation. I am excited to see how my students will translate the theme into poetry.

Teaching students about Kristallnacht is an opportunity for students to critically examine pivotal moments in history and to consider how their own actions or silence in the times in which they live will have far-reaching implications. As I have grown as an educator, inspired by the words of Anne Frank, Elie Wiesel, Kurt Messerschmidt, and others, I am gratified to have discovered the many ways that this history can be approached in my curriculum, and to have seen how this teaching not only promotes my students’ academic learning, but also their emotional and moral development as citizens of the world.

About the Author: Kristy Rush is an 8th grade English Language Arts educator at Pine Richland Middle School. She lives in Wexford, PA.

HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

Specificity matters. It shapes our memory, frames our perceptions, informs identity, and influences responses to the world around us.

I was reminded of this in January during the commemoration of International Holocaust Remembrance Day and the failure by the new White House administration to specifically mention the Jewish victims of the Holocaust. I was alarmed, offended, concerned, but, as a former teacher, I also wondered about the classroom teachers, navigating those choppy waters with students.