HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

TEACHING

This will be my twenty-ninth-year teaching and I still get butterflies in my stomach on the first day of school. I am consumed by nerves, anxiety, the thought of what more I need to do to be ready for the beginning of the school year. What should be taught, how it should be assessed, how to handle time constraints yet meet standards are the types of questions I, and frankly all educators, ponder as I lay out my courses. Fortunately, as a Holocaust educator, I feel empowered to meet these challenges thanks to the world class content and pedagogy I learned this summer at the 2023 Echoes & Reflections Advanced Learning Seminar. I am grateful that I was one of thirty talented educators selected from the United States to study for ten days at the International School For Holocaust Studies in Jerusalem with the purpose of improving our Holocaust education practice.

The power of the program is founded on its design, starting with the setting. Held at Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem, the program put us at the heart of Holocaust education with firsthand documents and accounts within arm’s reach. Added to the setting was the privilege to learn and collaborate with a fantastic cohort of educators from diverse backgrounds and experiences, each with a passion for Holocaust education. We learned from experts, including some of the best scholars in the world, a charismatic rabbi, and the last active Nazi Hunter from the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

The seminar was intense, but managed well, carefully organized, and systematic in its approach. Each day was integrated with content from Echoes & Reflections teaching Units and lesson plans, to complement presentations from experts in the field”. Within the 45-acre campus of Yad Vashem, we were given personalized tours of the Holocaust History Museum, the Valley of the Communities, , the Holocaust Art Museum, the Yad Vashem Archives, and the Garden of the Righteous Among the Nations, to name a few. Beyond the walls of Yad Vashem, we met Holocaust survivors in their home, had an inspiring, guided tour of the Old City of Jerusalem, and an unforgettable day trip to the Dead Sea and Masada.

Having described my experiences at Yad Vashem, I want to reflect on the impact they had on me as a life-long learner and teacher. For teachers, great professional development fills our cups and benefits student learning and outcomes. Coming away with something that can be implemented in the classroom immediately is my primary barometer of good professional development. We are always learning something; the key is what we will do with this knowledge. As a result of this Seminar, I aim to be more intentional about lifting people up when I teach the Holocaust, deemphasizing much of the darkness I focused on earlier in my career. Though I was well intentioned when I taught about the Nazi years, including the process of dehumanizing Jews and the sheer numbers of Jews and others murdered in Europe, I now plan on spending more energy contextualizing this important part of Jewish history, letting students know what life was like for ordinary people who happened to be Jewish. They were people with brothers, sisters, uncles, classmates, and teammates and they had hobbies and dreams. I hope to lift the voices and share the stories about these people and their memories. My students need to understand that antisemitism did not start with the Nazis; they need to know that it goes back two millennium, that this is the longest hatred we know, and to be mindful of how it festers today. They need to examine this history and the many choices that were made and understand the cost of letting down our guard to bigotry, fear, and hatred.

This vision of student outcomes that are inspiring and mobilizing is what permeates my preparation this year. What I learned in the Echoes & Reflections Advanced Learning Seminar is crucial to students at this moment and in this country. Never forget.

About the author: Bradley E. Sultz is a proud teacher and advocate of public education and teaches at iPrep Academy, a highly recognized school in Miami, Florida. Bradley teaches AP Psychology, AP World History: Modern, Honors World History, AP Macroeconomics, and Honors Economics and is an AP World History: Modern Reader for the College Board, an AP World History: Modern Teacher Trainer and Teacher Mentor for Miami-Dade County Public Schools (the third largest school district in the country), and a Holocaust Education Advocate.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

TEACHING

As the wheels touched down at Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv, Israel, the real adventure began: the opportunity to participate in the Echoes & Reflections Advanced Seminar for Educators at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. Israel is about as different as it gets compared to my ranching community in the rolling Sandhills of rural Nebraska; and even though I have traveled quite a bit, this part of the world was totally new to me. On the outside I tried to keep my demeanor calm, however, on the inside my heart and mind were thrilled…and a little nervous. This is what happens when we allow ourselves to say yes to adventure. Take the leap. Teaching became even more enjoyable for me when I figured out that I could mesh my profession with my passions. Not only do these kinds of opportunities enhance my school and community, but these experiences also elevate my humanity and how I interact with the world.

What did I learn?

- During the intense 10-day seminar my mind encountered a not-so-little shift in how I approach the Holocaust with my students. I am the only English teacher at my school in rural Nebraska, so I have the unique opportunity to build my Holocaust units year upon year. The seminar at Yad Vashem made it clear to me that I have room for improvement. Living in a community with no Jewish people, one of the reasons I wanted to attend this seminar was to gain a better understanding of Jewish culture, traditions, history, and perspectives. My pen actually ran out of ink because of all the notes I took! Now that I have increased knowledge about Jewish life, and with the help of Echoes & Reflections, I can better pass on what I’ve learned to my students in a responsible way, using heavily vetted resources and personal testimony. This upcoming school year I will be using several lesson plans from Echoes & Reflections, particularly Unit 1. Studying the Holocaust, Lesson 2: Prewar Jewish Life.

- English teachers are known to be sticklers about word choice, and during one of the sessions, I was reminded about how the precision of language is vitally important when we teach about the Holocaust. For example, terms such as the “Final Solution” and extermination camps are perpetrator language, so educators must use caution when using these words with students. Words matter. As we continue to witness a rise in Holocaust denial and distortion, it is more important than ever to educate ourselves on appropriate and precise language when speaking about the Holocaust to our students and community members.

- One particularly powerful day was our trek to the Garden of the Righteous Among the Nations. I have a very personal connection to a Holocaust survivor who was saved by someone bestowed with this honor: a non-Jew who put himself and his family at mortal risk to save Jews during the Holocaust and received no compensation. I was three years old when I first met a Holocaust survivor named Sally, and through the years I have told Sally’s story and she has done numerous video chats with my students. Sally and her family were saved by Stanislaw Grocholski, who hid 15 people in his attic in rural Poland for two years. Stanislaw was named a Righteous and it was important for me to find his name in the Garden. While our group was in the Garden, Sheryl Ochayon, Project Director at Yad Vashem for Echoes & Reflections and one of our leaders, asked if I would tell Stanislaw’s story. After I finished, Sheryl said, “Megan, you know the story well, but there’s one thing you don’t know. Sally is my aunt. My mother was in that attic, too.” Immediately I was crying. Sheryl was crying. Our cohort was crying. It was an incredible moment that will stay with me for a lifetime. Sheryl said that some members of her family often wonder why she chose her job, and she said, “This is exactly why I do what I do. Megan lives in the middle of Nebraska in a town of 150 people with no Jewish community. And yet, each and every year she tells my family’s story and the story of Stanislaw.” I think about all of the people connected to the Holocaust and on that day, in that space, two people from different parts of the world, created a bond. Yad Vashem highlights the importance of giving victims and survivors their faces and names back. We need to hear their voices and see them as full people: before, during, and after the Holocaust.

Megan Helberg & Sheryl Ochayon, Project Director at Yad Vashem for Echoes & Reflections

I am eager to share what I learned during my time at Yad Vashem, about the importance of learning from multiple perspectives, and how vital it was for me to learn about the Holocaust while physically being in Israel surrounded by Jewish life. My experience at the Echoes & Reflections seminar cannot be replicated anywhere else, and I am grateful to have Echoes & Reflections lesson plans to help me appropriately teach what I learned to my students. Something I have come to recognize is that just because my students are from a rural area, it does not mean they are any less eager to learn. They simply need an opportunity, and I can offer them this important learning experience.

With that said, teachers, this is your chance to make the leap. Apply for programs that will enhance you professionally and personally. Be the person that brings these learning opportunities to your students, no matter where they call home. Just think, next year you may be telling the story of when the wheels of your airplane touched down in Israel.

About the author: Megan Helberg lives and teaches English in rural Nebraska where she is surrounded by the rolling Sandhills. She is the 2020 Nebraska Teacher of the Year and passionate about traveling the world in order to bring back as much knowledge and love and opportunities as she can for her students.

CURRENT EVENTS

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

As we know, a Tennessee school board voted recently to ban use of the graphic novel Maus in its 8th grade classrooms. Sadly, the losers in this fight are – as always – the students, for whom a great work of literature is erased. Interestingly, the winner by a landslide is Maus – sales of which have skyrocketed on Amazon since the ban, and free copies of which are set to be provided to students. All this proves that banning books can be quite the boomerang.

Books can open new worlds. They can spark imagination. They can transport readers to different places, show them different perspectives, and introduce them to different ideas. But not when they are banned.

Those of us who teach the Holocaust know the value of books. Readers can literally explore the unknown and transcend physical boundaries: this is why so many ghettos during the Holocaust had libraries and so many imprisoned and persecuted people – especially children – read books. In December, 1942 in Vilna, even after tens of thousands of Jews had been murdered and death was all around, the ghetto library held a ceremony marking the loan of the 100,000th book. In the Warsaw ghetto, children continued to borrow books during the Great Deportation in the summer of 1942 during which almost 300,000 Jews were murdered. Often the books they borrowed were never returned; they were packed into the bundles the children took with them to the Treblinka death camp. "The ghetto child, robbed of the world—the river, the green trees, freedom of movement—could win all this back through the magic of the printed word."[1]

For these reasons, books hold a special reverence for us.

The Supreme Court has agreed, holding in Board of Education v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982) that the First Amendment limits the power of officials to remove books[2] from school libraries.[3]

It turns out that book banning goes back at least as far as Plato in 360 B.C.[4] For as long as books have been written, there have been those who have pushed to ban them. Even classic literature such as Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and classic authors such as Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, have been challenged. In 2001 student access to the "Harry Potter" book series was challenged (because of references to witchcraft and the occult). Those who support book bans generally fear that the books in question present ideas, raise issues or provoke critical inquiry that they find inappropriate. Yet, isn't that the function of education? Don't we want to support freedom of thought, of expression, of speech? Don't we want students to explore new issues and to think for themselves? Often, challenged books are entry points into difficult subjects that need to be discussed.

This is why it's so sad for the students of McMinn County to lose a book like Maus over eight curse words and one ostensibly objectionable picture.

Maus is a brave and unflinching work. It is the author's father's first-person, eyewitness account of the Holocaust. As such, it functions as Holocaust history through a personal story (something Echoes & Reflections firmly advocates). But it is also the author, Art Spiegelman’s, account of his relationship with his aging survivor father, and how he experienced writing about the experience of being a survivor's son. On this level it depicts the process of transmitting and recording memory and trauma, and how the present is continuously shaped by the past.

Maus is both an authentic Holocaust story and a story of the "second generation" – its honesty without sentimentality is what makes it so memorable and powerful. In its pages are discrimination, persecution and hate, as well as resilience, resistance and perseverance: all very human, very real, very gritty. Nothing is sugar-coated; this is part of its appeal.

What distinguishes Maus still more is that it is written as a graphic novel, where mice are used to represent Jews, Germans are represented by cats, and other ethnic groups are represented by other animals. It is an allegory: the Germans viewed Jews not as people, but as vermin, which is why the book begins with a quote by Adolf Hitler, “The Jews are undoubtedly a race, but they are not human.” Spiegelman has said that his anthropomorphic characters call attention to the absurdity of dividing people up into different animal groups, and take Hitler’s rhetoric to turn the notion of the subhuman back on itself by letting the mice “stand on their hind legs and insist on their humanity.” Using animal characters allowed Spiegelman to say otherwise unsayable things and show events too disturbing to show.

For all of these reasons, Maus won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992, and is read today in many high schools as well as in college courses. It brings new insights to the study of the Holocaust. And for all of these reasons, the ban in Tennessee has boomeranged – the school board may believe it is protecting the county's students from eight curse words and an objectionable picture, but the students will be deprived of these insights and of a great work of literature.

To learn how to teach with Maus, join Echoes & Reflections webinar “Bringing Maus to the Classroom” on 2/23 at 3 PM ET. Register here.

About the author: Sheryl Ochayon is the Director of Echoes & Reflections for Yad Vashem.

[1] Rachel Auerbach, "The Librarians", PaknTreger, Summer 2017, https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/language-literature-culture/pakn-treger/2017-pakn-treger-translation-issue/librarians.

[2] The list of books at issue included such classics as The Fixer, by Bernard Malamud; Slaughterhouse Five, by Kurt Vonnegut Jr.; and Black Boy, by Richard Wright, called by the Board of Ed, "anti-American…and just plain filthy."

[3] The opinion’s scope was narrow because the case did not involve textbooks or required reading, but the Court sang the praises of books, libraries and broadening students’ worlds through reading.

[4] For an interesting summary of censorship of books and ideas through the centuries, see Claire Mullally and Andrew Gargano, “Banned Books”, Freedom Forum Institute, 2017, https://www.freedomforuminstitute.org/first-amendment-center/topics/freedom-of-speech-2/libraries-first-amendment-overview/banned-books/.

CURRENT EVENTS

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

In the United States and across the globe, there is an all-out assault on Jews arising from the political left, political right, and seemingly everywhere in between. From virulent and overt violence to the dog whistles of antisemitic tropes, one can see antisemitism alive and growing in almost every facet of life. In a survey conducted by ADL, over 1 billion out of 4 billion people surveyed across the world harbor antisemitic attitudes. That is over 25%. As the Program Manager for Echoes & Reflections, my career is focused on helping secondary educators effectively and responsibly teach about the Holocaust and contemporary antisemitism. This work has been inspired by my previous role in the classroom and the reaction to antisemitism I saw in my own students.

As a non-Jew teaching in Catholic high schools, I am almost positive that I never had a Jewish student. By my sixth year teaching in 2019, the project Eva’s Stories premiered in January on Instagram. Filmed utilizing the platform’s unique features, it was a modern way to tell the story of one person’s experience of the Holocaust. Although I mostly taught Catholic theology, I often engaged my students with contemporary issues, what was happening in the news, and what I was learning in my graduate program in Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Before I started the day’s lesson, we watched the first few stories posted on the Instagram account and discussed briefly what the students thought about telling such an important story using the platform.

With our conversation finished, I went over to my computer to change the big screen to project my PowerPoint for that day’s lesson. A student spoke up and asked what the echo symbol in the comment section was ((())). I answered, informing the student that it was a tool used by antisemites to denote who was Jewish on the internet and thus open them up to harassment and vitriol. I remember saying it matter-of-factly. Even though this student didn’t know what the echo symbol was, I assumed they knew that Jews were constantly bombarded with antisemitic abuse on the internet. I was mistaken. The student was horrified by my simple explanation. She was completely unaware of the cesspool of violent Jew-hate that floods the internet. Although probably not the safest response in hindsight, I began scrolling through the comments as account after account spewed antisemitic tropes, degrading rhetoric, and pure hatred to an Instagram post that had been created to teach a factual and what should be a non-controversial topic.

We often think of antisemitism as a core belief of antisemites similar to how we view Adolf Hitler and the Nazis: consumed with a violent hatred of Jews and a desire to rid the Earth of them by murdering every last one. Yes, there are plenty of antisemites that believe in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, indulge in the wildest conspiracy theories, and base their entire worldview on the evil Jew. They are ignorant, hateful, dangerous, and frankly, a small minority in the world of antisemitism. They may be the most dangerous of committing acts of terror and murdering Jews today, but they are on the fringes of society and do not pose the same level of threat as the systems, institutions, and public antisemitism that has infiltrated human society for generations.

My students were not antisemites by this definition and most likely will never join a Neo-Nazi movement or engage in the violent actions of these radical extremists. I think we could say that about the majority of people in the United States and certainly the vast majority of students who have been fortunate enough to have caring parents and guardians, good teachers, and placed value in their education. That is not to say, however, that my students were not antisemitic. They were raised and educated in a system that perpetuates antisemitism, that utilizes dog whistles to rally the most extreme in our society to persuade us to believe that their fringe beliefs are mainstream, and who have been bombarded with antisemitic tropes in their social media. For some of them, like the young woman who asked about the echo symbol in my class, they are unaware that antisemitism exists today and yet know the negative stereotypes that have been used for centuries and may even accept them as true when it fits their agenda.

Have you ever asked an older person, whether it be a grandparent or someone else, a question, and the answer you get makes you cringe? I can remember my grandmother telling me about the “nice Chinaman” who helped her at the gas station. When I discuss antisemitism with teachers and students, I often use the example of my uncle claiming at the breakfast table while reading the newspaper, “Well of course it says that since the Jews control the media.” These were not people I would describe as ignorant, hateful, or antisemites and yet it is clear that the system in which they were raised imbued in them a latent racism and antisemitism. This is how antisemitism continues to exist even after the horrors of the Holocaust and why it is so easy for it to escalate and erupt once again: it is always there in our society. It always exists in our systems, in our institutions, in our government, in our education, and in almost every other facet of our lives. Latent antisemitism remains a fact in human society.

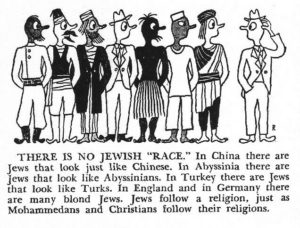

Antisemitism burns uncontrollably when fueled by ignorance and fear, but that is not where it is first learned, taught, and manifests itself in each individual. Antisemitism morphs, changes, adapts and is perverted to fit the current landscape but its existence within the systems that are part of human society remains. It will take exhaustive education, understanding, empathy, compassion, and courage to combat the systems and create a just society that includes Jews. In their formative years, most young people do not encounter Jews on a regular basis, if at all. They are even less likely to learn about Jewish life, culture, diversity, and all the wonderful aspects of Judaism. They have no connection to Jews or real knowledge of what it means to be a Jew. They have no evidence to disprove the seemingly endless conspiracy theories and vitriol aimed at Jews from nearly every direction. They are fed lies from their earliest development about Jews, especially when they do not know any.

Young non-Jews need education (as do plenty of adults). They need experiences learning about Jews and Jewish life. They need to discover the traditions, the history, and the people. They need to be invited into various aspects of Jewish life, from religious services to Passover Seder. They also need to understand the nature of antisemitism as illogical, baseless, and yet ever-present, with the potential to escalate at any time. With the knowledge of the beauty of Jews and Judaism with the ever-constant threat that Jews face, they will be empowered to advocate for and protect their new Jewish friends. Understanding this can help young people combat blatant lies and slander with the truth, empower young Jews to be proud of their heritage and share their beliefs and culture with others to cultivate empathy and understanding, and be inspired to reach out and bring non-Jews into the fight against antisemitism.

For those victims who have had to endure and continue to endure antisemitism, it is a personal and emotionally harrowing experience. As a non-Jew, I can sympathize with Jews, but I cannot truly empathize with that horrible experience as it is one that I will most likely never have to endure. But a clueless non-Jew who doesn’t know antisemitism still exists or just how prevalent it is? That is an experience that I truly understand, through my own upbringing and in the eyes of my former students. We may never be able to educate and change the minds and hearts of violent extremists who are determined to wreak havoc and endanger Jewish lives, but the vast majority of antisemites just need to be educated and empowered to act against antisemitism. It may be an illogical and baseless hatred, but it exists and grows in a scientific and systematic way, especially recently as the ADL has tracked over 2,000 antisemitic incidents in the United States for each of the last two years. We must work to dismantle the systems in place that perpetuate antisemitism while engaging with young people to understand its nature, why it is disgusting and wrong, and what can be done to combat it.

About the author: Jesse Tannetta is a former high school teacher who is now the Program Manager for Echoes & Reflections. He holds a master’s degree in Holocaust and Genocide Studies and is a current Ph.D. student beginning his dissertation on female concentration camp guard Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan.

This article was originally published in The Lookstein Center of Bar-Ilan University’s Jewish Educational Leadership Fall 2021 issue, Jewish Education Amidst Rising Antisemitism. This journal issue, with articles from Jewish communal leaders and experts, explores the educational implications for Jewish students of rising antisemitism. Read the full article here and access the full journal for free here.

CURRENT EVENTS

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

This blog originally appeared in The Dallas Morning News.

When a school administrator in Southlake implied there exists an “opposing” perspective on the Holocaust that teachers are obligated to present, it set off a firestorm and broached some fundamental questions about the nature and necessity of Holocaust education in America.

The controversy sets the stage for important reflection on inclusivity and multiple perspectives in today’s classrooms. While there are not multiple perspectives about whether the Holocaust happened, as the school district later acknowledged with an apology, there are varying points of entry for understanding what happened, why it happened, and what the ongoing impact is. The more angles and perspectives we add to our educational and societal approach, and the more modes of engagement we have, the better equipped we are to learn the lessons of the past.

As an educator and historian, I must state unequivocally that there is no opposing view as it pertains to the facts of the Holocaust, the systematic murder of 6 million Jews. This is indisputable and is supported by a mountain of primary and secondary source evidence. The “opposing” view of the fact of the Holocaust is Holocaust denial. From a historical perspective, this is not presenting multiple sides of an argument, it is countering fact with conspiracy theories and lies. We cannot lose sight of that. Responsible Holocaust education helps prevent us from losing sight of that.

We have evidence that Holocaust education is essential in helping young people understand the past as well as develop an ability to engage with and respect multiple perspectives. A recent study by Echoes & Reflections found that Holocaust education in high school increased historical knowledge and cultivated more empathetic, tolerant and engaged students. The study also found that learning from Holocaust survivor testimony is strongly associated with numerous positive outcomes in early adulthood, including superior critical thinking skills and a greater sense of social responsibility. Our archive at USC Shoah Foundation house 51,000 accounts from Holocaust survivors. These individual perspectives help us learn and grow. The foundation’s entire Visual History Archive includes accounts of Jewish Holocaust survivors as well as liberators, political prisoners, LGBTQ, Sinti and Roma survivors and other witnesses. Together, these testimonies illuminate the lived experiences of the Holocaust. We all learn more when afforded the opportunity to hear from powerful voices that can connect diverse populations and transcend generations. Our brains are hard-wired to learn from storytelling, something that independent research affirms time and time again.

Adopting a multi-perspective view of history also means including voices that we may not always feel comfortable listening to. Our friend and colleague, the late Luke Holland, had a vision of documenting the voices of former Nazi perpetrators and bystanders for the recent documentary, Final Account. Cognizant of this powerful, age-old teaching tool, USC Shoah Foundation partnered with Participant and Focus Features to include these perspectives in teaching materials designed to help students understand the power and persistence of pernicious thinking, even decades after the fact.

Simultaneously, as recently reported by The New York Times, many Holocaust museums and organizations are updating their content and including voices from other genocides and social justice movements to reinforce the messages of “never again” that have echoed since World War II. The Holocaust Memorial Resource and Education Center of Florida, in Orlando, recently opened an exhibit exploring the indelible link between white supremacy and antisemitism, through the perspective of acclaimed blues musician Daryl Davis. This year, Holocaust Museum Houston’s first juried exhibition in its new building was “Withstand: Latinx Art in Times of Conflict,” exploring “themes of social justice and human rights through 100 artworks by Houston Latinx artists.” This inclusive vision of teaching about the past brings Holocaust education into dialogue with contemporary issues that still plague society.

These educational institutions, and many others, understand that the study and memorialization of the Holocaust are enriched when we add diverse points of entry for people to understand both the historical reality of the genocide and consider the contemporary impact on their thinking and actions. We can and should use all responsible avenues of open inquiry, creative approaches, and engagement with even the most challenging material as we grapple with the horrors of the past.

There is no “opposing” view of the Holocaust, but there is value in drawing on multiple perspectives in understanding the experience and impact of it. The perspectives of eyewitnesses can provide students with the tools needed to recognize the continuing relevance and importance of one of the world’s greatest crimes and equip them to build a better future.

About the author: Dr. Kori Street is the incoming interim executive director and senior director of programs and operations of USC Shoah Foundation.

CURRENT EVENTS

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

A few years back, in front of an audience of a hundred school administrators and educators focused on implementing Holocaust education, one thoughtful participant shared how the study of the Holocaust, particularly the study of the Nazis’ anti-Jewish policy, can be an important opportunity for students to connect this to the US’s Jim Crow laws passed after the Civil War. I didn’t scan the room but I imagined that his remarks may have landed uncomfortably on some participants for reasons ranging from the unsettling idea of the US as a “beacon of freedom” being a model of racist policies and practices for Nazi Germany to the discomfort and insufficient knowledge and ability to broach such a discussion in the classroom. Without skipping a beat, I smiled and agreed with him wholeheartedly, and encouraged folks to read James Q. Whitman’s book Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law (2017).

The book’s title can easily offend those who believe in the idea of America as the land of the free. Just the hint of a connection between America and Nazi Germany can make such persons uneasy. Because Holocaust survivors in the US found safe haven and in many cases thrived in this country, so the logic goes, how could this same country be the source of inspiration and guidance for Nazi Germany’s efforts to dehumanize and destroy the Jewish people? But if those same people read this book, they would be confronted with a well-researched, evidence-based documentation of how Nazi politicians and lawyers tackled the creation of their “race law” by looking to the US. Early on in the book, Whitman states, “In the early 1930s the Nazis drew on a range of American examples, both federal and state. Their America was not just the South; it was a racist America writ much larger. Moreover, the ironic truth is that when Nazis rejected the American example, it was sometimes because they thought the American practices were overly harsh”(5).

As educators, we may have heard our students – particularly students of color and LGBTQ+ students – advance a burgeoning connection: How an anti-Jewish law or decree reminds them of our country’s racist segregation laws or our ban on interracial and same-sex marriages. This is the moment where we are confronted with a choice: how do we respond?

Do we provide a tepid acknowledgment or else a statement that this is not the same thing, and continue with the prepared lesson? Are we even confident and competent enough to navigate this huge “aha” moment? Whitman implores us to dive right into the discussion without hesitation. “America was the leader [in racist law making] during the age of the rise of Hitler. That is the truth, and we cannot squirm away from it” (139). There are consequences to racist, dehumanizing policies, not only on targeted communities whose lives were severely compromised or cut short because of them but also on other countries watching closely to gauge the effectiveness and success of these policies. Simply put, that’s what the Nazis did with our country’s racist policies. There is a need to reckon with this truth, that the US inadvertently but nonetheless significantly became a model for the anti-Jewish policies in Germany.

Whitman does a huge service by evidencing the intentional and thorough discussions of US racist policies – not just Jim Crow segregation laws but also its racist immigration laws, citizenship laws, and miscegenation laws – in key Nazi reports, articles, memos and meetings that contributed to the crafting of the 1935 Nuremberg Laws. He explores the crafting of the Reich Citizenship Law – the second of the three Nuremberg Laws – by highlighting the Nazis’ keen interest in America’s anti-immigration laws (namely its race-based quotas) and citizenship laws with its creation of de jure and de facto forms of second-class citizenship – not only for Black Americans, but also for Puerto Ricans, Filipina/o/x, Chinese and Native Americans – that maintained our country’s racial hierarchy and power. While these anti-immigration laws were more inspirational rather than serving as a blueprint for the Nazis, more critical and closely examined were the US anti-miscegenation laws that informed the third of the Nuremberg Laws – the Blood Law, which banned race mixing in sex and marriage between Jewish and non-Jewish Germans. Here, Whitman argues, is where “we discover the most provocative evidence of direct Nazi engagement with American legal models, and the most unsettling signs of direct influence” (76). He highlights the legal techniques -- policies and procedures -- that Americans employed to justify their “race madness” as the source of influence for the Nazis. Simply put, Whitman writes, “The United States offered the model of anti-miscegenation legislation...and it is in the criminalization of racially mixed marriage [in the US] that we see the strongest signs of direct American influence on the Nuremberg laws” (78-29).

Whitman’s book provides educators with a valuable opportunity to connect with the Holocaust, particularly the anti-Jewish laws, within US history of race-based immigration, segregation, citizenship, and interracial marriages. Connection points to consider include:

1. The invitation to students to connect these two histories is as easy as using the worksheet “What Rights are Important to Me” in the Nazi Germany unit. Many educators who have used this in their classrooms have shared stories of students seeing the natural connection: “Voting wasn’t allowed by the Black community after Reconstruction,” or “Asians who were able to immigrate to the US weren’t eligible for citizenship and couldn’t even vote,” or even “This country didn’t allow people of the same sex to get married for a long time.” This is the actualizing of one of our pedagogical principles: Making the Holocaust relevant.

2. Encourage inquiry-based learning and critical thinking, specifically when viewing visual history testimony. Students, with their US-centric 21st-century lens, need brave educators to guide them in applying the lessons of the Holocaust to our own racist history without “squirm(ing) away from it.” This connection is not saying that the anti-Jewish laws and the assortment of US racist laws are the same; Whitman states very clearly that they are not carbon copies. However, we should not downplay or brush aside these connections as they are truly linked. Let’s use these moments to face our own ugly truths and discuss them openly and critically, knowing that our country’s racist laws and practices played a significant role in providing the Nazis with a model that informed their efforts to create their own dehumanizing legal system.

We as educators can no longer rely on the excuse that because we were not taught about racism in our elementary and high school classes, we are ill-equipped to teach and navigate these discussions in our classrooms. It may be an explanation of our shortfalls, but not an absolution of taking on this mantle. We also cannot turn our heads from the indignities that many Americans suffered in our country’s history while exalting inspirational values and focusing only on the good. Such silence is a practice in denial, and is an anathema to the education profession. Current legislation in some states to restrict teaching about the realities of the racism embedded in our laws, policies and practices is codifying this silence, and denies students a robust and honest education.

Our student population – growing in its racial and ethnic diversity, and its connection to the global community – cannot be burdened by and held back because of our denials, fears, and excuses. We owe it to them to put our learner hat on, find our courage, and delve into this history and its implications, to guide our students to become critical historians and work toward a model of justice and human dignity for all.

About the author: Esther K. Hurh is a highly seasoned education consultant with over 25 years of experience in facilitation, training, curriculum development and program management. In addition to her work with Echoes & Reflections as its senior trainer since 2014, she is deeply interested in the areas of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), social justice education, and Asian American history.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

TEACHING

As a slightly younger educator, I came into the classroom with excitement and high hopes for teaching about the Holocaust. I had attended a reputable university that prided itself on turning out engaging and informed teachers who had undergone rigorous coursework and tight scrutiny during student teaching placements. One of my crowning achievements was crafting a complete Holocaust unit that I was eager to implement with students in my own classroom, an opportunity I had two years into my teaching career when I was allowed to create an “Introduction to Holocaust History” elective.

At this point in my career, I had not had any formal training on teaching the Holocaust. I had the privilege of learning from an excellent Holocaust historian and had just enrolled in a Holocaust and Genocide Studies MA program at a nearby university. I felt confident and well-equipped to work with my students, a sentiment that I now shake my head at after over a decade and a half of professional development in this field. I couldn’t wait to implement the cornerstone activity in my unit – a simulation fostered by my skilled university education professor that crowded students into a corner of my classroom while reading a short piece that had them imagining they were in a boxcar.

I look back now on that memory and that situation with a mix of shame and revelation. I subjected my students to this experience the first two years I taught the course, and it was not until I met my future mentor, Elaine Culbertson, that I realized just how misguided this practice was. At that time, Elaine was the facilitator of a conference I attended, and she pointed out that simulations, using the boxcar example, were never appropriate in the context of Holocaust education. She challenged their promotion by saying that thankfully, our students were having these experiences inside of climate-controlled classrooms, with school lunches in their bellies and a measure of stability in most of their lives. She explained that our students couldn’t understand this scenario, nor should we traumatize them into thinking that they could.

This was a transformative moment for me, and I am grateful that Elaine and resources like Echoes & Reflections came into my life. Through the use of these carefully curated resources and further professional development, my outlook on teaching the Holocaust significantly changed. I placed at the core a mantra Elaine shared with me – my job as an educator was “to lead my students safely in and safely out of this topic,” each and every day. I could do this by choosing responsible, age-appropriate content to share with my students and make sure that I was presenting it to them with suitable methodological approaches.

Within this context, I learned that instead of sharing images of dead bodies, my students were just as impacted by a picture of empty, piled up clothing. The latter did not give them nightmares and turn them away, instead it compelled questions and thoughts about the human beings who wore those clothes, shoes, and wedding rings. I also learned that memoirs and visual history testimony captivated my students in a way fictional films and books never could. Instead of leaving my class thinking that they “knew how it was” my students left with questions that they wanted to explore further and for some, it sparked paths into lifelong learning.

As educators, we have a significant responsibility to our students to lead them safely in and safely out of Holocaust content. To help you avoid or correct some of the same mistakes I made, I offer the following suggestions:

- Avoid having students rationalize/justify the thinking of perpetrators. Instead, ask them to explore the roots of Nazi racial ideology and how it was spread to the populations of Germany and occupied Europe. Echoes & Reflections Unit 2: Antisemitism contains structured lessons to help students reach these understandings by posing inquiry-driven questions and asking students to examine primary sources such as speeches and propaganda illustrations.

- Remember to keep the social and emotional well-being of your students at the forefront of your planning and rationale when choosing resources. Consider having students examine photographs from the Auschwitz Album instead of showing them post-death photos. The victims did not give their permission to be photographed in either scenario, but in the former, they are clothed and shown as human beings versus as a mass of anonymous, frightening corpses in the latter.

- Be sure to consider the age level of your students. While students may outwardly project maturity at young ages, research by educators such as Simone Schweber, author of Making Sense of the Holocaust: Lessons from Classroom Practice, show that introducing the more difficult aspects of the Holocaust at too young an age can actually repel students from feeling comfortable studying it in the future. When working with students in younger age groups, such as the middle school level, consider focusing more on the prewar life of Jews in Europe or on topics such as how Jews lived in the ghettos versus focusing on the horror of the Final Solution. Echoes & Reflections recently introduced new resources on prewar Jewish life in Unit 1: Studying the Holocaust. Our Unit 4: The Ghettos has some powerful pieces of poetry and other imagery that is also more appropriate for middle school learners.

- Select activities that ask students to critically approach the history and build empathy through the use of resources such as testimony instead of suggesting that students “simulate” events from this horrific era. Don’t ask students what they would do but ask them how testimonies like that of the late Roman Kent share what was done and the difficult choices that came along with these decisions.

- As my mentor Elaine, an Echoes & Reflections trainer, taught me years ago keep the mantra that Echoes espouses, “lead your students safely in and safely out” of this history, at the forefront of your efforts.

Ultimately, know that you are not alone in teaching this challenging history. If you have taken a misstep like I did early in my career, it’s never too late to do it better the next time around. Today, I am proud to share my mistakes as the Curriculum & Instruction Specialist for Echoes & Reflections and to let you know that this program is always here to support you in that effort.

About the Author: Jennifer Goss currently serves as the Curriculum and Instruction Specialist for Echoes & Reflections. A 19-year veteran Social Studies teacher, Jennifer holds dual MAs in Holocaust & Genocide Studies and American History.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

LITERATURE

As this school year comes to a close—another surrounded by the devastating impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, increased violence and hate against the AAPI community, rising antisemitism, and other acts of racial injustice—members of our community share recommended books about the Holocaust, featuring stories of rescue, resistance, hope, and humanity in the face of tragedy, that may be a source of inspirational reading material over the summer months.

The Bielski Brothers: The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Built a Village in the Forest, and Saved 1,200 Jews

By Peter Duffy

Reviewed by Lynne R. Ravas

The Echoes & Reflections resource Students’ Toughest Questions helps  educators prepare informed and thoughtful responses to challenging topics addressed in the classroom. The question, “Why didn’t the Jews fight back?” is one I heard repeatedly from my students, their parents and guardians, colleagues, and other interested people. Understanding life in a shtetl in Eastern Europe in the 1930s can be difficult for adults and students who have little exposure to lifestyles and religious traditions. Television, movies, and books about the Holocaust and Jewish life do not always address in depth the religious and moral beliefs of the victims. The Bielski Brothers: The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Built a Village in the Forest, and Saved 1,200 Jews by Peter Duffy presents the decisions and reasonings when a group of Jewish people did choose to fight back. Furthermore, their main priority was keeping all the Jews who sought safety with them alive. The philosophy, as expressed by Tuvia Bielski, was: “Don’t rush to fight and die. So few of us are left, we need to save lives. It is more important to save Jews than to kill Germans”. Duffy helps the reader understand these choiceless choices the Jewish people faced as well as the decisions they ultimately made. The reader is exposed to the harsh realities of how to fight back and save fellow Jews while weighing the religious beliefs as well as the moral beliefs of individuals and groups. As an educator, understanding what decisions were made under those particular circumstances will help students better comprehend the realities of fighting back and the power of spiritual resistance.

educators prepare informed and thoughtful responses to challenging topics addressed in the classroom. The question, “Why didn’t the Jews fight back?” is one I heard repeatedly from my students, their parents and guardians, colleagues, and other interested people. Understanding life in a shtetl in Eastern Europe in the 1930s can be difficult for adults and students who have little exposure to lifestyles and religious traditions. Television, movies, and books about the Holocaust and Jewish life do not always address in depth the religious and moral beliefs of the victims. The Bielski Brothers: The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Built a Village in the Forest, and Saved 1,200 Jews by Peter Duffy presents the decisions and reasonings when a group of Jewish people did choose to fight back. Furthermore, their main priority was keeping all the Jews who sought safety with them alive. The philosophy, as expressed by Tuvia Bielski, was: “Don’t rush to fight and die. So few of us are left, we need to save lives. It is more important to save Jews than to kill Germans”. Duffy helps the reader understand these choiceless choices the Jewish people faced as well as the decisions they ultimately made. The reader is exposed to the harsh realities of how to fight back and save fellow Jews while weighing the religious beliefs as well as the moral beliefs of individuals and groups. As an educator, understanding what decisions were made under those particular circumstances will help students better comprehend the realities of fighting back and the power of spiritual resistance.

For more information on the Bielski Brothers, educators can also view this article from Yad Vashem.

About the reviewer: Lynne Rosenbaum Ravas retired from teaching and began presenting with the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh's Generations Program. In addition to serving as a facilitator for Echoes & Reflections, she volunteers with the Federal Executive Board's Hate Crimes Working Group, FBI's Citizens' Academy, and other organizations in the Pittsburgh area.

Stories about Dita Kraus, the “Librarian of Auschwitz”

Reviewed by Kim Klett

I must confess; I typically avoid any recent book that has the name “Auschwitz” in it. Look at what American publishers did to Primo Levi’s incredible If This is a Man, changing the title to Survival in Auschwitz, as if readers wouldn’t understand the original title. Lately, I have seen too many poorly written, poorly researched novels on Auschwitz, and my guess is that publishers believe the name Auschwitz will sell copies, since there is an interest in Holocaust and WWII-related books. Recently, though, I had several readers tell me how much they liked Antonio Iturbe’s The Librarian of Auschwitz. I was surprised to find it in the young adult section at my favorite local bookstore, but immediately liked the fact that it names the librarian of the title, Dita Kraus, on the front cover. A few pages in, I was hooked. Iturbe did his research, telling a much broader version of what I had heard about Birkenau’s “family camp,” which consisted mostly of Czechoslovakian Jews, among them Dita Kraus, a 14-year-old girl there with her parents. The “library” consisted of eight books, all taken from suitcases on the ramp, and each lovingly taken care of and hidden away, except when it was safe to share them. Readers witness the selections that take place in this special camp, the interactions with the notorious Mengele, and daily life for some of the children there. The narration is beautiful, reminding me a little bit of The Book Thief; it definitely keeps the pages turning. Iturbe also includes a postscript, explaining how he got the information and what happened to the people whose lives unfold in the book. This is where I started searching for more books on the topic, and also highly recommend Dita Kraus’ beautiful memoir, A Delayed Life: The True Story of the Librarian of Auschwitz. While the memoir does not say a lot about her time in the “family camp”, it is rich with details of her life in Prague before the war, as well as her post-war life. I appreciate this because so many Holocaust memoirs focus mainly on the time in the camps, and while that is important, it is also crucial to see survivors’ full lives. Another book I checked out is one written by Dita’s husband, Ota Kraus, a novel called The Children’s Block. It is an interesting complement to the novel and to Dita’s memoir, but not one I would use in my classroom. I will be using both The Librarian of Auschwitz and excerpts from Dita Kraus’s memoir next year and I cannot wait to share them with my students.

“Auschwitz” in it. Look at what American publishers did to Primo Levi’s incredible If This is a Man, changing the title to Survival in Auschwitz, as if readers wouldn’t understand the original title. Lately, I have seen too many poorly written, poorly researched novels on Auschwitz, and my guess is that publishers believe the name Auschwitz will sell copies, since there is an interest in Holocaust and WWII-related books. Recently, though, I had several readers tell me how much they liked Antonio Iturbe’s The Librarian of Auschwitz. I was surprised to find it in the young adult section at my favorite local bookstore, but immediately liked the fact that it names the librarian of the title, Dita Kraus, on the front cover. A few pages in, I was hooked. Iturbe did his research, telling a much broader version of what I had heard about Birkenau’s “family camp,” which consisted mostly of Czechoslovakian Jews, among them Dita Kraus, a 14-year-old girl there with her parents. The “library” consisted of eight books, all taken from suitcases on the ramp, and each lovingly taken care of and hidden away, except when it was safe to share them. Readers witness the selections that take place in this special camp, the interactions with the notorious Mengele, and daily life for some of the children there. The narration is beautiful, reminding me a little bit of The Book Thief; it definitely keeps the pages turning. Iturbe also includes a postscript, explaining how he got the information and what happened to the people whose lives unfold in the book. This is where I started searching for more books on the topic, and also highly recommend Dita Kraus’ beautiful memoir, A Delayed Life: The True Story of the Librarian of Auschwitz. While the memoir does not say a lot about her time in the “family camp”, it is rich with details of her life in Prague before the war, as well as her post-war life. I appreciate this because so many Holocaust memoirs focus mainly on the time in the camps, and while that is important, it is also crucial to see survivors’ full lives. Another book I checked out is one written by Dita’s husband, Ota Kraus, a novel called The Children’s Block. It is an interesting complement to the novel and to Dita’s memoir, but not one I would use in my classroom. I will be using both The Librarian of Auschwitz and excerpts from Dita Kraus’s memoir next year and I cannot wait to share them with my students.

Explore Yad Vashem’s online exhibition, The Auschwitz Album, the only surviving visual evidence of the process leading to the mass murder at Auschwitz-Birkenau, to learn more about the Jewish experience in these camps.

About the reviewer: Kim Klett has taught English at Dobson High School in Mesa, Arizona, since 1991, and developed a year-long Holocaust Literature course there. She is a senior trainer for Echoes & Reflections, the deputy executive director for the Educators' Institute for Human Rights (EIHR), and a Museum Teacher Fellow with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

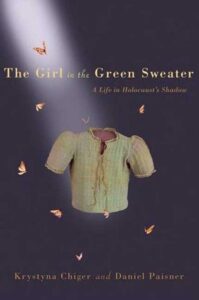

The Girl in the Green Sweater

By Krystyna Chiger & Daniel Paisner

Reviewed by Scott Hirschfeld

While searching for resources to support a lesson on extraordinary actions taken by ordinary – even flawed – people during the Holocaust, I stumbled across Leopold Socha, the Polish sewer worker and unlikely savior of a group of ten Jewish people. Socha’s story is part of a broader tale of survival recounted by Krystyna Chiger (later known as Kristin Keren) in her gripping memoir, The Girl in the Green Sweater.

taken by ordinary – even flawed – people during the Holocaust, I stumbled across Leopold Socha, the Polish sewer worker and unlikely savior of a group of ten Jewish people. Socha’s story is part of a broader tale of survival recounted by Krystyna Chiger (later known as Kristin Keren) in her gripping memoir, The Girl in the Green Sweater.

Krystyna Chiger was born in 1935 in Lwów, Poland. At age 8, she had already lived two lives. The first half resembled, in her words, a "character from a storybook fable.” The daughter and granddaughter of successful textile merchants, Krystyna enjoyed a life of privilege in the midst of a bustling metropolis with a large Jewish population. This all changed when Krystyna was four years old and the Soviets occupied eastern Poland, followed by the Nazis two years later. By 1943, the Chiger family had lost their livelihood, their home, and their independence, and were forced into the ghetto in the north of Lwów.

As the Nazis prepared to invade the ghetto for a final “action” in May 1943, Krystyna's father, Ignacy, led the family to a secret hiding place he had prepared with an alliance of other men in the sewers beneath their ghetto dwelling. A group of 70 desperate escapees quickly dwindled to 20 and then 10 despairing souls, enduring against all odds in a rat-infested, fetid cavern for fourteen months. The Jews survived with the devoted assistance of three Polish sewer workers. The leader of the group, Leopold Socha, was a reformed criminal who sought redemption for past transgressions through kindness to others.

The Girl in the Green Sweater is noteworthy not just for its astonishing story of escape and survival, but for the humanity and moral complexity that Chiger brings to the unlikely assemblage of people. All of their stories are told with compassion and layered with the impossible ethical dilemmas forced upon a beleaguered people. Chiger’s most empathetic reflections are dedicated to her beloved Socha, who she says, “saw us as human beings instead of as a group of desperate Jews willing to give him some money for protection.”

Most of the ten Jewish escapees rescued by Socha survived the war and went on to rebuild their lives. As of this writing, Krystyna Chiger is the last surviving member of that group. The Girl in the Green Sweater may not be appropriate in its entirety for all student audiences due to the disturbing details of survival, but it is well worth sharing select passages that convey the humanity, hope, and courage of the Jewish survivors and their rescuers. And students can view the book’s namesake – the green sweater knit by Krystyna’s beloved grandmother and which kept her warm through the years of her ordeal – at the Unites States Holocaust Memorial Museum, where it was part of a hidden children’s exhibition.

To learn more about Krystyna Chiger view her IWitness testimony, found in Echoes & Reflections teaching unit: Rescuers and Non-Jewish Resistance.

About the reviewer: Scott Hirschfeld has worked as an elementary and middle school teacher in the New York City schools and has led social justice education programs for several leading non-profit organizations, including ADL. Scott is currently a freelance diversity and anti-bias educator based in New Jersey and is part of the team working to update the Echoes & Reflections lesson plans and teaching units.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

SURVIVORS

UNCATEGORIZED

“…If you ever survive this war tell everyone how we went. Tell everyone how you said good-bye to me and remember one thing. Wherever you may be always wear a nice clean shirt and be clean. If someone throws a rock at you then throw them back bread.”

These are the words that Holocaust survivor Maurice Markheim will never forget. They comprise the indelible message that is etched into his memory as the last conversation he had with his mother.

When we viewed this piece, we were struck by these poignant and heartfelt words of love and kindness as well as the way in which Evan Hong, an eighth grader at Mariners Christian School in Costa Mesa, California, memorialized them by creating a wire silhouette as an art project her school submitted for Chapman University’s 21st Annual Holocaust Art and Writing Contest.

Last year, thousands of middle and high school students from across the United States and seven other countries, watched survivor video testimonies and responded to the contest prompt through prose, poetry, art, or film. This year’s contest, now in its 22nd year, challenges students to reflect upon and interpret the theme, “Sharing Strength: Sustaining Humanity.”

To prepare students to participate in the contest, many teachers turn to Echoes & Reflections, a valued partner in the contest, for professional development and to help them provide historical context to the testimonies that students watch. This year, Chapman University will team up with Echoes & Reflections to offer a contest-specific professional development program to highlight key resources that align with the contest, as well as effective strategies to further student engagement with the testimonies they view.

In our respective roles as the Associate Director and Education Consultant for the Rodgers Center at Chapman University, we have seen the contest grow tremendously over the years. What we think continues to be particularly appealing and, perhaps why many teachers participate year after year, is the contest’s way of combining study of the Holocaust with the hands-on participation in the arts, offering students a platform and a voice to process and express their thoughts and reactions and to make their own, individual meaning.

In fact, this contest might offer even greater benefits to those participating. Authors Brian Kisida and Daniel H. Bowen, write in their Brookings Institute blog, New Evidence of the Benefits of Arts Education, that participation in the arts challenge us with different points of view, compel students to empathize with “others,” and give us the opportunity to reflect on the human condition.1

For example, Noa Nerwich, a middle school student from King David Linksfield School in South Africa, drafted the following poem based on the testimony of Holocaust survivor Ruth Halbreich. It examines how a simple, everyday object, a “Maroon Hankie,” became a meaningful, everlasting and valued connection to her father.

Cleanly pressed and folded it was placed into my hand

A last token of a soon to be memory

I received a maroon hankie

I didn’t know the value of objects, until had one

I didn’t know the value of people, until I had none.

But my one object carried all the worth in the world

A maroon hankie

I don’t know what happened to him

All I know is the walls were rising

And there were bombs, more people dying

And Warsaw was in flames: Red, licking flames

Like the colour of my maroon hankie

We watched the window, havoc unleashed on our home

Yet we were the opportune, we were on the right side of the window pane

The side where we still wore silky dresses made by the sisters.

The same silk of my maroon hankie.

I was lucky

Not because I was saved

But because I learned the true meaning of love

His love was sewn into my heart

The same way I held the hankie so tight at night

That its fibers have sewn into the fibers of my skin

Because of my father’s honour I survived

Because of his love for us he died

He sacrificed it all so we could breathe the air of freedom

To the man who gave to me

The thing that has carried all of my tears

A maroon hankie

His maroon hankie

This year as we commemorated the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the camps we were reminded that today’s students are the last generation to hear directly from the survivors. As we look to the future, one of the lasting artifacts we have are the survivors’ precious video testimonies, a permanent record that captures their stories, warnings, and memories. The testimonies also stand as the fulfillment of a promise that the eyewitnesses made to each other during the Holocaust, in which they vowed if they survived to tell the story, to let the world know what happened and to do their utmost to assure that these events would never be forgotten. Students who participate in the contest have now become their “messengers of memory,” the ones entrusted with perpetuating this vow for generations to come and, as a recent survey has shown, their exposure to Holocaust survivor testimony can support them in building a better future.

This year’s contest information is now available and educators are invited to participate.

For more information: Annual Holocaust Art & Writing Contest

Contact: Jessica MyLymuk at cioffi@chapman.edu, (714) 532-6003

Note: Last year, Chapman University had to cancel its 21st Annual Holocaust Art & Writing Contest awards ceremony, which was scheduled on March 13, 2020, due to the Coronavirus. A virtual program is posted on the contest website and can be watched here.

About the authors:

Jessica MyLymuk is the Associate Director at the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education at Chapman University and oversees the planning and implementation for the Annual Holocaust Art & Writing Contest.

Sherry Bard is an Education Consultant for the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education and a Senior Training Specialist for the Echoes & Reflections program.

CURRENT EVENTS

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

In the fall of 1968, Margaret Michaels stood in front of her middle school American History class and shared a difficult truth: her 99.99% white school district had accepted its first Black teacher from Central State University in nearby Wilberforce. At the time, the Beavercreek School District covered fifty square miles of suburban and rural families in the southwestern portion of Ohio. Over seven thousand students filled the high school, two middle schools, and seven elementary schools, and most of the faculty, staff, and administration lived in the community. Some of these individuals still carried the names of the founding families who settled in the area as Ohio emerged from the unexplored west. Parents worked in major industry, owned mom and pop businesses, and farmed the land, and raised the livestock. Busing was a topic of discussion, usually out of earshot of children, as demands for desegregation for the students of the West End of Dayton grew. The West End was home to most of the Black community members, while the North Side housed the synagogue. Unspoken yet clearly understood lines had been drawn long ago. Parents worried that forced busing would send their children to the questionable neighborhoods just outside the township’s borders.

Margaret Michaels, one of the most honest and courageous people I have ever known, explained to her students that day that she was prejudiced. She related how her family ardently believed in the inferiority of Black people. She explained how having a Black friend or dating a Black person was completely beyond the realm of reality in her community and would have resulted in being disowned by her family. She described her qualms about meeting this student teacher and working with him. Mrs. Michaels went so far as to admit that she asked him if she could touch his hair since she had never come in physical contact with a Black person before that moment. Then, Mrs. Michaels explained that although her family would never understand or accept her changing attitude, she was admitting her prejudice and taking responsibility for letting go of the hatred and seeing the individual human, as well as the greater Black community, for who he is: a person deserving of respect and equal rights and access; a person with hopes, skills, and ideas just like anyone else in the world.

Margaret Michaels opened my eyes and my mind when she bravely explained that she chose to change the way she judged people. More than fifty years later, I can still see her standing there telling us that we alone are responsible for our thoughts, actions, and beliefs. We may choose to use the excuse of our upbringing, our families, our friends, our religious institutions, or anything else, but ultimately, we must own our stance in this world.

It is difficult, uncomfortable, and even embarrassing, at times, to speak out when family, friends, or colleagues disagree vehemently. But we must. We must hold up the mirror as individuals and as a country to see honestly why we are where we are in 2020. This requires ongoing reflection and learning and is a fundamental principle that has guided me throughout my personal and professional life. Our responsibility as educators is to show our own discomfort with past and present decisions and actions and impart this value to our students. We must also admit our failings, our moments of hesitation, our fear of speaking up, and speaking out. Just as we admit when we do not have an immediate answer, one that requires additional thought or research, we must admit that we are humans who have and will again fail our fellow humans. That does not excuse our shortcomings; it makes us work harder to acknowledge our own prejudices and fears of peer pressure.

As a Holocaust educator, I could not discuss the prejudice and hateful actions of the Nazis and their collaborators without discussing other examples of hatred around the world and throughout history in the U.S. Pointing a finger at Germany in 1944 is easy; but looking honestly at ourselves and our past is immensely uncomfortable. Yet, we must own that while we may not have personally forced Native Americans to walk the Trail of Tears, or forced those of Japanese descent into internment camps, or enforced the Jim Crow Laws, or supported the sundown laws for People of Color, or denied women equal pay, and the list goes on, we are obligated to fully acknowledge how these pieces of history have caused damage to both the human spirit and body and have consequences that continue to impact us today. It is long past time to stand up for what we know is right in this country.

When I speak with groups about the Holocaust, I do so not just to teach history, but to show the power of one individual. One perpetrator, one victim, one rescuer, one bystander – each has the power to change the world at that moment. The survivors I have met have talked about spiritual resistance which might have included practicing their religious beliefs in Auschwitz, listening to a scholar in the Warsaw Ghetto, or sharing food in hiding. One person can make a difference, and one person can change the world.

Margaret Michaels made her choice and accepted the consequences. When I look at my grandson, I try to see the legacy I will leave for him as a citizen of this country and of this world. I think of my paternal grandparents who decided to travel to Nazi Germany to bring one orphaned Jewish child to the safety of their home in the United States. I believe that most people are loving, caring individuals with the capacity to make the world better, but I also know that our voices and our actions are the only tools that can make long-lasting and positive change.

About the author: Lynne Rosenbaum Ravas retired from teaching and began presenting with the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh's Generations Program. In addition to serving as a facilitator for Echoes & Reflections, she volunteers with the Federal Executive Board's Hate Crimes Working Group, FBI's Citizens' Academy, and other organizations in the area.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

TEACHING

This piece was originally published in The English Pub (April 2020 Newsletter, pg 22-23).

In March, in the middle of the virus onset, conferences I had planned to attend began cancelling. Papers I’d workshopped with friends were put on hold, and opportunities to reconnect with colleagues and reinvigorate my inspiration to teach evaporated. It was about that time that I remembered the Echoes & Reflections organization I’d learned about at an NCTE convention. I’m always shy about undertaking new adventures alone, so I talked it over with a friend who teaches mathematics and together we embarked on an April training course in Teaching the Holocaust: Empowering Students.

I know quite a bit about the British Civil War and Victorian cultural shifts, but I know embarrassingly zip about 20th century history, so I had a lot to learn. I’d never puzzled over the meaning of the term “antisemitism” before. I didn’t realize that Jews weren’t allowed to be teachers. I wasn’t aware that a vast archive of firsthand records and artifacts is available to those who incorporate Holocaust studies in their classroom curriculum.

In this course designed primarily for middle and high school teachers, I was able to identify the connections I need to make in my university classes—to Shakespeare plays, to William Blake’s Romantic poetry, and to John Ruskin’s declarations that architecture tells the story of a culture if we read it with care and attention.

I learned about “bystanders” and “liberators” and the importance of defining such terms for students who are investigating Holocaust history for what may be their first encounter. I made note of the Glossary of terms Echoes & Reflections provides. I dove into the vast video archive and watched Paul Parks tell his story about meeting a woman who remembered him and his kindness from when she was a little girl in Dachau concentration camp and he was a soldier in uniform come to save her. His words, quoting hers, “I know you by your eyes” still echo in my soul as testimony of the importance of showing compassion to every child we encounter.

I learned about the Kindertransport that saved Jewish children by tearing families apart. I found a ready link to the Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child. I examined the Pedagogical Principles for Effective Holocaust Instruction and considered their insistence that teachers Use Primary Source Materials, Encourage Inquiry-Based Learning and Critical Thinking, and Foster Empathy. These sound pedagogical approaches adapt readily to all that ELA teachers in Arkansas attempt in our classrooms, so the effectiveness of this direction rings true.

I took part in these webcasts: “`Who Will Write Our History?’: A Special Conversation with Director Roberta Grossman,” “Mindful Exploration: Resilience in Times of Change,” and “Echoes of Night: Personal Reflections from Elie Wiesel’s Student.” I connected with IWitness, part of the USC Shoah Foundation, and learned to create assignments there enabling students to access a wealth of video testimonials recording the accounts of witnesses.

There was no way to plumb the vast extent of free resources available to teachers in the three weeks I had, particularly as one of them was spent dodging tornadoes and without electricity and the other two were spent navigating my students’ transition to online learning and modifying and implementing my formula for assessing their performance. Final grades, after all, were due before the work for my course was complete. Nevertheless, I got a glimpse of the possibilities, and I have the summer before me.

I made note of the upcoming webcast Sherry Bard will offer on July 1st, “Creating Context for Teaching Night” and have bookmarked the link to other upcoming webcasts sponsored by Echoes & Reflections. Whether we directly teach Holocaust studies in our curriculum or not, developing a sensitivity to the topic and a sympathetic means of introducing it to students is essential to helping them understand the importance of an empathetic response to the world they live in.

The information I gleaned from my participation in the course has implications in my own classrooms as I teach research skills, composition, world literature, Shakespeare, and other courses. It will help me discuss the importance of developing communication skills and the responsibilities that come with education. It will help me explore with my students the importance of recognizing and defending the humanity of every child. It will enable me to share with them the power of voice that a treasury of records and primary documents provides, and it will highlight the wonder of memory.

ELA classrooms in Arkansas, or their virtual cousins, can feel a world away from the gritty realities of concentration camps in World War II Eastern Europe, but we have local the relics of Japanese internment camps in Jerome to remind us and reason enough to thank God the outcomes of those moments in Arkansas history differed from those of the Jews during the Holocaust.

About the author: Dr. Kay Walter is a Professor of English at University of Arkansas at Monticello. She can be contacted at walter@uamont.edu

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

SURVIVORS

The following is a reflection from Leah Warshawski, producer and co-director of the award-winning film about Holocaust Survivor Sonia Warshawski, Big Sonia. Leah will be joining an Echoes & Reflections Connecting Communities webinar in July to introduce the film to educators for their use in the classroom.

At this time when we are struggling through a global pandemic impacting our lives in the most profound and difficult ways, people are looking for models of resilience, unity, empathy, and hope. Sonia Warshawski, a 94-year old Holocaust survivor and my grandmother, is that kind of model.

In my film, Big Sonia, I sought to capture all of these emotions as Sonia shares her experiences with students, inmates, and her community - all from a small tailor shop in the bottom of a dead Kansas City mall. While the film is a poignant story of generational trauma and healing, it also offers a funny portrait of the power of love to triumph over bigotry and the power of truth-telling.

As I believe all teachers hope to achieve when they teach young people about the Holocaust or other atrocities in history, we wanted this film to inspire positive change in the world. That is why we ask viewers to spread the #SoniaEffect – to share what happens after people see the film and are fueled to action. Big Sonia has inspired people in ways we never imagined. Deeply moved by the film’s message, the Mayor of Kansas City declared an annual “Big Sonia Day” on December 21 to remind everyone of the power of kindness.