CURRENT EVENTS

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

This blog originally appeared in The Dallas Morning News.

When a school administrator in Southlake implied there exists an “opposing” perspective on the Holocaust that teachers are obligated to present, it set off a firestorm and broached some fundamental questions about the nature and necessity of Holocaust education in America.

The controversy sets the stage for important reflection on inclusivity and multiple perspectives in today’s classrooms. While there are not multiple perspectives about whether the Holocaust happened, as the school district later acknowledged with an apology, there are varying points of entry for understanding what happened, why it happened, and what the ongoing impact is. The more angles and perspectives we add to our educational and societal approach, and the more modes of engagement we have, the better equipped we are to learn the lessons of the past.

As an educator and historian, I must state unequivocally that there is no opposing view as it pertains to the facts of the Holocaust, the systematic murder of 6 million Jews. This is indisputable and is supported by a mountain of primary and secondary source evidence. The “opposing” view of the fact of the Holocaust is Holocaust denial. From a historical perspective, this is not presenting multiple sides of an argument, it is countering fact with conspiracy theories and lies. We cannot lose sight of that. Responsible Holocaust education helps prevent us from losing sight of that.

We have evidence that Holocaust education is essential in helping young people understand the past as well as develop an ability to engage with and respect multiple perspectives. A recent study by Echoes & Reflections found that Holocaust education in high school increased historical knowledge and cultivated more empathetic, tolerant and engaged students. The study also found that learning from Holocaust survivor testimony is strongly associated with numerous positive outcomes in early adulthood, including superior critical thinking skills and a greater sense of social responsibility. Our archive at USC Shoah Foundation house 51,000 accounts from Holocaust survivors. These individual perspectives help us learn and grow. The foundation’s entire Visual History Archive includes accounts of Jewish Holocaust survivors as well as liberators, political prisoners, LGBTQ, Sinti and Roma survivors and other witnesses. Together, these testimonies illuminate the lived experiences of the Holocaust. We all learn more when afforded the opportunity to hear from powerful voices that can connect diverse populations and transcend generations. Our brains are hard-wired to learn from storytelling, something that independent research affirms time and time again.

Adopting a multi-perspective view of history also means including voices that we may not always feel comfortable listening to. Our friend and colleague, the late Luke Holland, had a vision of documenting the voices of former Nazi perpetrators and bystanders for the recent documentary, Final Account. Cognizant of this powerful, age-old teaching tool, USC Shoah Foundation partnered with Participant and Focus Features to include these perspectives in teaching materials designed to help students understand the power and persistence of pernicious thinking, even decades after the fact.

Simultaneously, as recently reported by The New York Times, many Holocaust museums and organizations are updating their content and including voices from other genocides and social justice movements to reinforce the messages of “never again” that have echoed since World War II. The Holocaust Memorial Resource and Education Center of Florida, in Orlando, recently opened an exhibit exploring the indelible link between white supremacy and antisemitism, through the perspective of acclaimed blues musician Daryl Davis. This year, Holocaust Museum Houston’s first juried exhibition in its new building was “Withstand: Latinx Art in Times of Conflict,” exploring “themes of social justice and human rights through 100 artworks by Houston Latinx artists.” This inclusive vision of teaching about the past brings Holocaust education into dialogue with contemporary issues that still plague society.

These educational institutions, and many others, understand that the study and memorialization of the Holocaust are enriched when we add diverse points of entry for people to understand both the historical reality of the genocide and consider the contemporary impact on their thinking and actions. We can and should use all responsible avenues of open inquiry, creative approaches, and engagement with even the most challenging material as we grapple with the horrors of the past.

There is no “opposing” view of the Holocaust, but there is value in drawing on multiple perspectives in understanding the experience and impact of it. The perspectives of eyewitnesses can provide students with the tools needed to recognize the continuing relevance and importance of one of the world’s greatest crimes and equip them to build a better future.

About the author: Dr. Kori Street is the incoming interim executive director and senior director of programs and operations of USC Shoah Foundation.

CLASSROOM LESSONS

TEACHING

Set among the bucolic farm fields and rural communities of southern Wisconsin, Clinton, where I live and teach, is the quintessential American small town. The center of the community's social life is the Clinton Junior-Senior High School, which prides itself on traditions, such as the homecoming parade, chili and cinnamon roll fundraiser, and drive-your-tractor-to-school day.

Holocaust education is an equally valued part of children’s middle and high school experience in this community, from reading survivor memoirs and novels to the annual 8th-grade trip to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. By the time students enroll in my junior-senior “Genocide and Human Rights” elective course, most of them have studied the Holocaust numerous times in their social studies, English language arts, and German classes.

Studying the Holocaust can serve as a bridge for teachers and students to incorporate other instances of genocide and mass violence in the classroom, including the genocide of Indigenous peoples. While Holocaust education has become an integral part of the curriculum in Clinton, students have little knowledge or even awareness of the local histories of Indigenous genocide. Students often struggle to name the Ho-Chunk as the Indigenous nation whose ancestral land the town and school are located. Not unique to students in Clinton, in big cities and small towns across the United States, there is little awareness of Indigenous communities and the violence perpetrated against them.

I have found that in my “Genocide and Human Rights” course, students’ prior experiences learning about the Holocaust provide inroads for teaching about the genocide of Indigenous peoples. The pedagogical recommendations from Echoes & Reflections and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum are the bedrock of discussion on teaching hard history and are certainly applicable and advisable for teaching about other cases of genocide and mass violence. Recommendations, such as “contextualize the history” and “teach the human story,” are equally important in lessons on Indigenous genocide and the Holocaust, helping students understand the larger context that surrounds episodes of genocide and mass violence and the experiences of individuals. Furthermore, these principles have been guideposts to help me develop the following guidelines to support teaching about the genocide of Indigenous peoples.

Teach about Local Histories

In a neatly manicured park on the edge of Clinton stands the rough-hewn Skavlem-Williams Log Cabin, which, according to the accompanying historical marker, is a “visible reminder of the sacrifices made by early pioneers as they settled this area.”

Notably absent from the signage is any mention of the Indigenous inhabitants of this land. Like many communities across the United States, Clinton has a long history of excluding Indigenous peoples from local narratives that celebrate only Euro-American settlement and achievements. The practice of memorializing the “first” Euro-American settlers through monuments while simultaneously writing the perceived “last” Indigenous peoples out of existence is what Jean O’Brien (White Earth Ojibwe) referred to as “firsting and lasting.” In local histories, such practices further the myth of the “vanishing Indian,” or the notion that the Indigenous peoples vanished due to genocidal violence and assimilation by the end of the nineteenth century.

Examining this local signage inevitably leads my students to ask: who were the Indigenous peoples who lived on this land before the first Euro-American settlers arrived, what were their lives like, and, ultimately, what happened to them? These questions form the basis for our unit on Indigenous genocide. Fostering a classroom learning community that encourages students to ask such essential questions is the first step towards an inquiry-based approach to Holocaust and genocide education.

While students are generally aware of the so-called “Trail of Tears,” and some even may refer to this forced removal of tribes from the American southeast in the early 1830s as genocide, they know almost nothing about the local histories of dispossession and violence, such as the treaties that were signed with Indigenous communities or the Black Hawk War of 1832, which made Euro-American settlement possible in southern Wisconsin.

Teach about the Continuing Legacies of Genocide

Though one might point to specific events or instances of violence in nineteenth-century state or national history, the genocide of Indigenous peoples in North America has had far-reaching consequences stretching into the present. To elucidate the legacies of genocide for my students, I use Aaron Huey’s powerful TED Talk, “America’s Native Prisoners of War,” in which he uses contemporary photographs of the Pine Ridge Reservation, one of the poorest places in the United States, to show the legacies of centuries of dispossession, forced removal, and genocidal violence. Though it is important to show the realities of the legacies of violence for contemporary Indigenous peoples, communities have always resisted and survived, maintaining their cultural traditions, despite physical and cultural genocide. My students and I use a collection of video essays, “The Ways: Great Lakes Native Language and Culture,” to examine, for example, language revitalization efforts and the Manoomin (wild rice) harvest.

Partner with Local Indigenous Communities

If the opportunity presents itself, partnering with local Indigenous communities offers students an extremely powerful learning opportunity. Ho-Chunk oral tradition states, “we have always been here.” This unequivocal statement is a powerful salvo to challenge the exclusion and misrepresentation of Indigenous peoples that students have experienced in classrooms and curricula. Importantly, I partner with local Indigenous communities to provide opportunities for them to share their collective histories and individual stories. In this way, genocide becomes one part of the larger story of Indigenous peoples, which neither begins nor ends with colonization in the nineteenth century. Just as the Holocaust must be contextualized in the broader history of European and Nazi antisemitism, Indigenous genocide must be taught within the larger context of colonialism. Additionally, partnering with local Indigenous communities helps eschew the foods-and-festivals approach to teaching about “foreign” cultures for in-depth discussions of treaty rights, language revitalization, and tribal efforts to buy back ceded/stolen land. For many students, these are difficult discussions bridging histories of genocide and contemporary realities based on legacies of mass violence.

Recognize the Difficult Nature of Teaching and Learning About Indigenous Genocide

Teaching and learning about national and, especially, local histories of genocide perpetrated against Indigenous peoples is often difficult for non-Indigenous teachers and students. Such narratives challenge foundational stories about local communities and the United States, often evoking feelings of guilt and shame among white students. When left unprocessed, feelings of shame and guilt can result in minimization, distortion, and denial of Indigenous genocide in classrooms. Though teaching about difficult histories of violence in the United States may evoke feelings of guilt and shame, this should never be the goal of such lessons; rather, teaching and learning about difficult histories should provide opportunities to learn about historically marginalized groups, examine contemporary realities within society, and imagine and envision a more equitable future. As with Holocaust education, educators should focus on promoting empathy and understanding when teaching about Indigenous peoples and guide students "safely in and safely out" when teaching about Indigenous genocide.

Do Not Engage in Classroom Discussions that Minimize, Distort, and Deny Indigenous Genocide

Debates about the appropriateness of applying the term genocide to the experiences of Indigenous peoples, statements such as “Indigenous peoples were just as violent (if not more violent) to other Indigenous groups as the Europeans were towards them,” or sentiments, such as “the destruction of Indigenous peoples was simply the inevitable result of two cultures colliding,” serve to minimize, distort, and deny genocide. Like Holocaust denial and distortion, debating and rejecting claims of Indigenous genocide furthers misinformation and prejudice while disregarding the realities of colonization in North America.

My students immediately recognize that such attitudes can have far-reaching consequences for society. While students are quick to see that contemporary Germany offers one model for recognizing and atoning for difficult histories, I remind them that, within the American context, we must imagine and enact our own paths towards social justice. Indeed, we end our unit on Indigenous genocide by exploring several models of reparative justice from Canada to South Africa.

About the author: George Dalbo is a high school social studies teacher in rural south-central Wisconsin and a Ph.D. Candidate in Social Studies Education at the University of Minnesota. His teaching and research interests center on Holocaust, genocide, and human rights education in middle and high school social studies classrooms and curricula. He works with Echoes & Reflections to facilitate training and develop curricula on the Holocaust.

CLASSROOM LESSONS

CURRENT EVENTS

So, it’s that time of year again – back to school. For students, no matter their age, the beginning of a new school year is always stressful. Will their new teachers be interesting? Will their friends be in their classes? COVID doesn’t help. The old stressors are still around but new ones kick in, too. Will they be going to school physically or will learning be hybrid? Will they have to wear a mask? Maybe they have suffered personal loss during this health crisis, or fear that they or someone they love will get sick.

I found an unexpected source of comfort that has helped me deal with COVID, lockdowns and restrictions. Yes, there was Netflix and often, a little too much ice cream. But I found a surprising support group that included six teenagers, all going through teenage issues, who helped me get through each day. They aren't exactly your run-of-the-mill teenagers – Anni, Esther, Hannah, Jakub, Petr and Victor are teenagers who lived before WWII, and they are the beating heart of the new Echoes & Reflections lesson on Prewar Jewish Life. Writing about them meant entering their worlds – in Latvia, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Tunisia. It meant seeing life through their eyes and understanding their concerns.

Getting to know these six young people while writing the Prewar Jewish Life lesson helped distract me from quarantines, vaccines and the endless news cycle. I wanted to understand them better. I wanted to experience the world they lived in, a world that existed before the shadow of the Holocaust crept up on them. Who were they?

To figure this out, I poured over their diary entries. I scoured their old photographs. I searched for more and more clues about their lives, all at a time when I wasn’t able to go outside. They intrigued me and kept me from dwelling on the pandemic. They also led me to an astonishing realization, made even more potent by the circumstances. The more I immersed myself in their lives, the more I realized that human beings are all connected across time and space. We all face the same personal issues and challenges, no matter when and where we live.

This is the beauty of the Prewar Jewish Life lesson - its ongoing resonance. As Anni, Jakub, Esther, Petr, Hannah and Victor transported me into their worlds, I understood the universality of the human story. Each of these six teenagers was just starting to figure out who she/he was, as are today’s teenagers. Burning issues of identity were starting to bubble up to the surface: What do I want to be when I grow up? Will I fit in? Will I be religious or will I assimilate into secular society? What does my heritage mean to me? Should I rebel against my parents or toe the line? Should I be a vegetarian? Do I have the talent to become what I’ve always dreamed of becoming?

I was truly struck by how many of these questions reflected similar hopes, dreams, fears and life questions that many young people ask today, despite the fact that they live 80 years later and half a world away. This was an excellent confirmation of the Echoes & Reflections mantra: that teaching the human story is important and impactful.

Last school year was a tough one, and by the looks of it, this school year will not be any easier. Let the young people profiled in Echoes & Reflections show the students in your class that they all have much in common. Let them build empathy, as you teach the Holocaust, for the Jewish teenagers (and others) throughout Europe who were thrown into a horrific crisis. Let them transport your students across time and space to really connect with the human stories that were just taking shape. These young people are wonderful examples of the indomitable human spirit. They wrote and painted and pursued their dreams in a world that, unbeknownst to them, was soon to be destroyed. Let them show your students the enormity of what was lost during the dark years of the Holocaust. Hopefully, your students will resolve to be the kind of people who will do their share to make sure that atrocities like these will never happen again.

These past months have possibly been the most complicated and unnerving period your students will ever experience. To all of you, who have been there for them, teaching them, guiding them - Bravo!! Be proud that you supported them.

As we enter the new school year as well as the Jewish New Year, we at Echoes & Reflections would like to wish you all good health and much success this year, and a brighter future of greater tolerance, respect and empathy. May this new year herald a time of health and growth for all.

About the author: Sheryl Ochayon is the Director of Echoes & Reflections for Yad Vashem.

CURRENT EVENTS

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

A few years back, in front of an audience of a hundred school administrators and educators focused on implementing Holocaust education, one thoughtful participant shared how the study of the Holocaust, particularly the study of the Nazis’ anti-Jewish policy, can be an important opportunity for students to connect this to the US’s Jim Crow laws passed after the Civil War. I didn’t scan the room but I imagined that his remarks may have landed uncomfortably on some participants for reasons ranging from the unsettling idea of the US as a “beacon of freedom” being a model of racist policies and practices for Nazi Germany to the discomfort and insufficient knowledge and ability to broach such a discussion in the classroom. Without skipping a beat, I smiled and agreed with him wholeheartedly, and encouraged folks to read James Q. Whitman’s book Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law (2017).

The book’s title can easily offend those who believe in the idea of America as the land of the free. Just the hint of a connection between America and Nazi Germany can make such persons uneasy. Because Holocaust survivors in the US found safe haven and in many cases thrived in this country, so the logic goes, how could this same country be the source of inspiration and guidance for Nazi Germany’s efforts to dehumanize and destroy the Jewish people? But if those same people read this book, they would be confronted with a well-researched, evidence-based documentation of how Nazi politicians and lawyers tackled the creation of their “race law” by looking to the US. Early on in the book, Whitman states, “In the early 1930s the Nazis drew on a range of American examples, both federal and state. Their America was not just the South; it was a racist America writ much larger. Moreover, the ironic truth is that when Nazis rejected the American example, it was sometimes because they thought the American practices were overly harsh”(5).

As educators, we may have heard our students – particularly students of color and LGBTQ+ students – advance a burgeoning connection: How an anti-Jewish law or decree reminds them of our country’s racist segregation laws or our ban on interracial and same-sex marriages. This is the moment where we are confronted with a choice: how do we respond?

Do we provide a tepid acknowledgment or else a statement that this is not the same thing, and continue with the prepared lesson? Are we even confident and competent enough to navigate this huge “aha” moment? Whitman implores us to dive right into the discussion without hesitation. “America was the leader [in racist law making] during the age of the rise of Hitler. That is the truth, and we cannot squirm away from it” (139). There are consequences to racist, dehumanizing policies, not only on targeted communities whose lives were severely compromised or cut short because of them but also on other countries watching closely to gauge the effectiveness and success of these policies. Simply put, that’s what the Nazis did with our country’s racist policies. There is a need to reckon with this truth, that the US inadvertently but nonetheless significantly became a model for the anti-Jewish policies in Germany.

Whitman does a huge service by evidencing the intentional and thorough discussions of US racist policies – not just Jim Crow segregation laws but also its racist immigration laws, citizenship laws, and miscegenation laws – in key Nazi reports, articles, memos and meetings that contributed to the crafting of the 1935 Nuremberg Laws. He explores the crafting of the Reich Citizenship Law – the second of the three Nuremberg Laws – by highlighting the Nazis’ keen interest in America’s anti-immigration laws (namely its race-based quotas) and citizenship laws with its creation of de jure and de facto forms of second-class citizenship – not only for Black Americans, but also for Puerto Ricans, Filipina/o/x, Chinese and Native Americans – that maintained our country’s racial hierarchy and power. While these anti-immigration laws were more inspirational rather than serving as a blueprint for the Nazis, more critical and closely examined were the US anti-miscegenation laws that informed the third of the Nuremberg Laws – the Blood Law, which banned race mixing in sex and marriage between Jewish and non-Jewish Germans. Here, Whitman argues, is where “we discover the most provocative evidence of direct Nazi engagement with American legal models, and the most unsettling signs of direct influence” (76). He highlights the legal techniques -- policies and procedures -- that Americans employed to justify their “race madness” as the source of influence for the Nazis. Simply put, Whitman writes, “The United States offered the model of anti-miscegenation legislation...and it is in the criminalization of racially mixed marriage [in the US] that we see the strongest signs of direct American influence on the Nuremberg laws” (78-29).

Whitman’s book provides educators with a valuable opportunity to connect with the Holocaust, particularly the anti-Jewish laws, within US history of race-based immigration, segregation, citizenship, and interracial marriages. Connection points to consider include:

1. The invitation to students to connect these two histories is as easy as using the worksheet “What Rights are Important to Me” in the Nazi Germany unit. Many educators who have used this in their classrooms have shared stories of students seeing the natural connection: “Voting wasn’t allowed by the Black community after Reconstruction,” or “Asians who were able to immigrate to the US weren’t eligible for citizenship and couldn’t even vote,” or even “This country didn’t allow people of the same sex to get married for a long time.” This is the actualizing of one of our pedagogical principles: Making the Holocaust relevant.

2. Encourage inquiry-based learning and critical thinking, specifically when viewing visual history testimony. Students, with their US-centric 21st-century lens, need brave educators to guide them in applying the lessons of the Holocaust to our own racist history without “squirm(ing) away from it.” This connection is not saying that the anti-Jewish laws and the assortment of US racist laws are the same; Whitman states very clearly that they are not carbon copies. However, we should not downplay or brush aside these connections as they are truly linked. Let’s use these moments to face our own ugly truths and discuss them openly and critically, knowing that our country’s racist laws and practices played a significant role in providing the Nazis with a model that informed their efforts to create their own dehumanizing legal system.

We as educators can no longer rely on the excuse that because we were not taught about racism in our elementary and high school classes, we are ill-equipped to teach and navigate these discussions in our classrooms. It may be an explanation of our shortfalls, but not an absolution of taking on this mantle. We also cannot turn our heads from the indignities that many Americans suffered in our country’s history while exalting inspirational values and focusing only on the good. Such silence is a practice in denial, and is an anathema to the education profession. Current legislation in some states to restrict teaching about the realities of the racism embedded in our laws, policies and practices is codifying this silence, and denies students a robust and honest education.

Our student population – growing in its racial and ethnic diversity, and its connection to the global community – cannot be burdened by and held back because of our denials, fears, and excuses. We owe it to them to put our learner hat on, find our courage, and delve into this history and its implications, to guide our students to become critical historians and work toward a model of justice and human dignity for all.

About the author: Esther K. Hurh is a highly seasoned education consultant with over 25 years of experience in facilitation, training, curriculum development and program management. In addition to her work with Echoes & Reflections as its senior trainer since 2014, she is deeply interested in the areas of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), social justice education, and Asian American history.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

TEACHING

As a slightly younger educator, I came into the classroom with excitement and high hopes for teaching about the Holocaust. I had attended a reputable university that prided itself on turning out engaging and informed teachers who had undergone rigorous coursework and tight scrutiny during student teaching placements. One of my crowning achievements was crafting a complete Holocaust unit that I was eager to implement with students in my own classroom, an opportunity I had two years into my teaching career when I was allowed to create an “Introduction to Holocaust History” elective.

At this point in my career, I had not had any formal training on teaching the Holocaust. I had the privilege of learning from an excellent Holocaust historian and had just enrolled in a Holocaust and Genocide Studies MA program at a nearby university. I felt confident and well-equipped to work with my students, a sentiment that I now shake my head at after over a decade and a half of professional development in this field. I couldn’t wait to implement the cornerstone activity in my unit – a simulation fostered by my skilled university education professor that crowded students into a corner of my classroom while reading a short piece that had them imagining they were in a boxcar.

I look back now on that memory and that situation with a mix of shame and revelation. I subjected my students to this experience the first two years I taught the course, and it was not until I met my future mentor, Elaine Culbertson, that I realized just how misguided this practice was. At that time, Elaine was the facilitator of a conference I attended, and she pointed out that simulations, using the boxcar example, were never appropriate in the context of Holocaust education. She challenged their promotion by saying that thankfully, our students were having these experiences inside of climate-controlled classrooms, with school lunches in their bellies and a measure of stability in most of their lives. She explained that our students couldn’t understand this scenario, nor should we traumatize them into thinking that they could.

This was a transformative moment for me, and I am grateful that Elaine and resources like Echoes & Reflections came into my life. Through the use of these carefully curated resources and further professional development, my outlook on teaching the Holocaust significantly changed. I placed at the core a mantra Elaine shared with me – my job as an educator was “to lead my students safely in and safely out of this topic,” each and every day. I could do this by choosing responsible, age-appropriate content to share with my students and make sure that I was presenting it to them with suitable methodological approaches.

Within this context, I learned that instead of sharing images of dead bodies, my students were just as impacted by a picture of empty, piled up clothing. The latter did not give them nightmares and turn them away, instead it compelled questions and thoughts about the human beings who wore those clothes, shoes, and wedding rings. I also learned that memoirs and visual history testimony captivated my students in a way fictional films and books never could. Instead of leaving my class thinking that they “knew how it was” my students left with questions that they wanted to explore further and for some, it sparked paths into lifelong learning.

As educators, we have a significant responsibility to our students to lead them safely in and safely out of Holocaust content. To help you avoid or correct some of the same mistakes I made, I offer the following suggestions:

- Avoid having students rationalize/justify the thinking of perpetrators. Instead, ask them to explore the roots of Nazi racial ideology and how it was spread to the populations of Germany and occupied Europe. Echoes & Reflections Unit 2: Antisemitism contains structured lessons to help students reach these understandings by posing inquiry-driven questions and asking students to examine primary sources such as speeches and propaganda illustrations.

- Remember to keep the social and emotional well-being of your students at the forefront of your planning and rationale when choosing resources. Consider having students examine photographs from the Auschwitz Album instead of showing them post-death photos. The victims did not give their permission to be photographed in either scenario, but in the former, they are clothed and shown as human beings versus as a mass of anonymous, frightening corpses in the latter.

- Be sure to consider the age level of your students. While students may outwardly project maturity at young ages, research by educators such as Simone Schweber, author of Making Sense of the Holocaust: Lessons from Classroom Practice, show that introducing the more difficult aspects of the Holocaust at too young an age can actually repel students from feeling comfortable studying it in the future. When working with students in younger age groups, such as the middle school level, consider focusing more on the prewar life of Jews in Europe or on topics such as how Jews lived in the ghettos versus focusing on the horror of the Final Solution. Echoes & Reflections recently introduced new resources on prewar Jewish life in Unit 1: Studying the Holocaust. Our Unit 4: The Ghettos has some powerful pieces of poetry and other imagery that is also more appropriate for middle school learners.

- Select activities that ask students to critically approach the history and build empathy through the use of resources such as testimony instead of suggesting that students “simulate” events from this horrific era. Don’t ask students what they would do but ask them how testimonies like that of the late Roman Kent share what was done and the difficult choices that came along with these decisions.

- As my mentor Elaine, an Echoes & Reflections trainer, taught me years ago keep the mantra that Echoes espouses, “lead your students safely in and safely out” of this history, at the forefront of your efforts.

Ultimately, know that you are not alone in teaching this challenging history. If you have taken a misstep like I did early in my career, it’s never too late to do it better the next time around. Today, I am proud to share my mistakes as the Curriculum & Instruction Specialist for Echoes & Reflections and to let you know that this program is always here to support you in that effort.

About the Author: Jennifer Goss currently serves as the Curriculum and Instruction Specialist for Echoes & Reflections. A 19-year veteran Social Studies teacher, Jennifer holds dual MAs in Holocaust & Genocide Studies and American History.

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

LITERATURE

As this school year comes to a close—another surrounded by the devastating impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, increased violence and hate against the AAPI community, rising antisemitism, and other acts of racial injustice—members of our community share recommended books about the Holocaust, featuring stories of rescue, resistance, hope, and humanity in the face of tragedy, that may be a source of inspirational reading material over the summer months.

The Bielski Brothers: The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Built a Village in the Forest, and Saved 1,200 Jews

By Peter Duffy

Reviewed by Lynne R. Ravas

The Echoes & Reflections resource Students’ Toughest Questions helps  educators prepare informed and thoughtful responses to challenging topics addressed in the classroom. The question, “Why didn’t the Jews fight back?” is one I heard repeatedly from my students, their parents and guardians, colleagues, and other interested people. Understanding life in a shtetl in Eastern Europe in the 1930s can be difficult for adults and students who have little exposure to lifestyles and religious traditions. Television, movies, and books about the Holocaust and Jewish life do not always address in depth the religious and moral beliefs of the victims. The Bielski Brothers: The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Built a Village in the Forest, and Saved 1,200 Jews by Peter Duffy presents the decisions and reasonings when a group of Jewish people did choose to fight back. Furthermore, their main priority was keeping all the Jews who sought safety with them alive. The philosophy, as expressed by Tuvia Bielski, was: “Don’t rush to fight and die. So few of us are left, we need to save lives. It is more important to save Jews than to kill Germans”. Duffy helps the reader understand these choiceless choices the Jewish people faced as well as the decisions they ultimately made. The reader is exposed to the harsh realities of how to fight back and save fellow Jews while weighing the religious beliefs as well as the moral beliefs of individuals and groups. As an educator, understanding what decisions were made under those particular circumstances will help students better comprehend the realities of fighting back and the power of spiritual resistance.

educators prepare informed and thoughtful responses to challenging topics addressed in the classroom. The question, “Why didn’t the Jews fight back?” is one I heard repeatedly from my students, their parents and guardians, colleagues, and other interested people. Understanding life in a shtetl in Eastern Europe in the 1930s can be difficult for adults and students who have little exposure to lifestyles and religious traditions. Television, movies, and books about the Holocaust and Jewish life do not always address in depth the religious and moral beliefs of the victims. The Bielski Brothers: The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Built a Village in the Forest, and Saved 1,200 Jews by Peter Duffy presents the decisions and reasonings when a group of Jewish people did choose to fight back. Furthermore, their main priority was keeping all the Jews who sought safety with them alive. The philosophy, as expressed by Tuvia Bielski, was: “Don’t rush to fight and die. So few of us are left, we need to save lives. It is more important to save Jews than to kill Germans”. Duffy helps the reader understand these choiceless choices the Jewish people faced as well as the decisions they ultimately made. The reader is exposed to the harsh realities of how to fight back and save fellow Jews while weighing the religious beliefs as well as the moral beliefs of individuals and groups. As an educator, understanding what decisions were made under those particular circumstances will help students better comprehend the realities of fighting back and the power of spiritual resistance.

For more information on the Bielski Brothers, educators can also view this article from Yad Vashem.

About the reviewer: Lynne Rosenbaum Ravas retired from teaching and began presenting with the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh's Generations Program. In addition to serving as a facilitator for Echoes & Reflections, she volunteers with the Federal Executive Board's Hate Crimes Working Group, FBI's Citizens' Academy, and other organizations in the Pittsburgh area.

Stories about Dita Kraus, the “Librarian of Auschwitz”

Reviewed by Kim Klett

I must confess; I typically avoid any recent book that has the name “Auschwitz” in it. Look at what American publishers did to Primo Levi’s incredible If This is a Man, changing the title to Survival in Auschwitz, as if readers wouldn’t understand the original title. Lately, I have seen too many poorly written, poorly researched novels on Auschwitz, and my guess is that publishers believe the name Auschwitz will sell copies, since there is an interest in Holocaust and WWII-related books. Recently, though, I had several readers tell me how much they liked Antonio Iturbe’s The Librarian of Auschwitz. I was surprised to find it in the young adult section at my favorite local bookstore, but immediately liked the fact that it names the librarian of the title, Dita Kraus, on the front cover. A few pages in, I was hooked. Iturbe did his research, telling a much broader version of what I had heard about Birkenau’s “family camp,” which consisted mostly of Czechoslovakian Jews, among them Dita Kraus, a 14-year-old girl there with her parents. The “library” consisted of eight books, all taken from suitcases on the ramp, and each lovingly taken care of and hidden away, except when it was safe to share them. Readers witness the selections that take place in this special camp, the interactions with the notorious Mengele, and daily life for some of the children there. The narration is beautiful, reminding me a little bit of The Book Thief; it definitely keeps the pages turning. Iturbe also includes a postscript, explaining how he got the information and what happened to the people whose lives unfold in the book. This is where I started searching for more books on the topic, and also highly recommend Dita Kraus’ beautiful memoir, A Delayed Life: The True Story of the Librarian of Auschwitz. While the memoir does not say a lot about her time in the “family camp”, it is rich with details of her life in Prague before the war, as well as her post-war life. I appreciate this because so many Holocaust memoirs focus mainly on the time in the camps, and while that is important, it is also crucial to see survivors’ full lives. Another book I checked out is one written by Dita’s husband, Ota Kraus, a novel called The Children’s Block. It is an interesting complement to the novel and to Dita’s memoir, but not one I would use in my classroom. I will be using both The Librarian of Auschwitz and excerpts from Dita Kraus’s memoir next year and I cannot wait to share them with my students.

“Auschwitz” in it. Look at what American publishers did to Primo Levi’s incredible If This is a Man, changing the title to Survival in Auschwitz, as if readers wouldn’t understand the original title. Lately, I have seen too many poorly written, poorly researched novels on Auschwitz, and my guess is that publishers believe the name Auschwitz will sell copies, since there is an interest in Holocaust and WWII-related books. Recently, though, I had several readers tell me how much they liked Antonio Iturbe’s The Librarian of Auschwitz. I was surprised to find it in the young adult section at my favorite local bookstore, but immediately liked the fact that it names the librarian of the title, Dita Kraus, on the front cover. A few pages in, I was hooked. Iturbe did his research, telling a much broader version of what I had heard about Birkenau’s “family camp,” which consisted mostly of Czechoslovakian Jews, among them Dita Kraus, a 14-year-old girl there with her parents. The “library” consisted of eight books, all taken from suitcases on the ramp, and each lovingly taken care of and hidden away, except when it was safe to share them. Readers witness the selections that take place in this special camp, the interactions with the notorious Mengele, and daily life for some of the children there. The narration is beautiful, reminding me a little bit of The Book Thief; it definitely keeps the pages turning. Iturbe also includes a postscript, explaining how he got the information and what happened to the people whose lives unfold in the book. This is where I started searching for more books on the topic, and also highly recommend Dita Kraus’ beautiful memoir, A Delayed Life: The True Story of the Librarian of Auschwitz. While the memoir does not say a lot about her time in the “family camp”, it is rich with details of her life in Prague before the war, as well as her post-war life. I appreciate this because so many Holocaust memoirs focus mainly on the time in the camps, and while that is important, it is also crucial to see survivors’ full lives. Another book I checked out is one written by Dita’s husband, Ota Kraus, a novel called The Children’s Block. It is an interesting complement to the novel and to Dita’s memoir, but not one I would use in my classroom. I will be using both The Librarian of Auschwitz and excerpts from Dita Kraus’s memoir next year and I cannot wait to share them with my students.

Explore Yad Vashem’s online exhibition, The Auschwitz Album, the only surviving visual evidence of the process leading to the mass murder at Auschwitz-Birkenau, to learn more about the Jewish experience in these camps.

About the reviewer: Kim Klett has taught English at Dobson High School in Mesa, Arizona, since 1991, and developed a year-long Holocaust Literature course there. She is a senior trainer for Echoes & Reflections, the deputy executive director for the Educators' Institute for Human Rights (EIHR), and a Museum Teacher Fellow with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

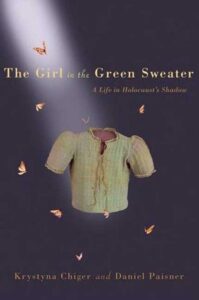

The Girl in the Green Sweater

By Krystyna Chiger & Daniel Paisner

Reviewed by Scott Hirschfeld

While searching for resources to support a lesson on extraordinary actions taken by ordinary – even flawed – people during the Holocaust, I stumbled across Leopold Socha, the Polish sewer worker and unlikely savior of a group of ten Jewish people. Socha’s story is part of a broader tale of survival recounted by Krystyna Chiger (later known as Kristin Keren) in her gripping memoir, The Girl in the Green Sweater.

taken by ordinary – even flawed – people during the Holocaust, I stumbled across Leopold Socha, the Polish sewer worker and unlikely savior of a group of ten Jewish people. Socha’s story is part of a broader tale of survival recounted by Krystyna Chiger (later known as Kristin Keren) in her gripping memoir, The Girl in the Green Sweater.

Krystyna Chiger was born in 1935 in Lwów, Poland. At age 8, she had already lived two lives. The first half resembled, in her words, a "character from a storybook fable.” The daughter and granddaughter of successful textile merchants, Krystyna enjoyed a life of privilege in the midst of a bustling metropolis with a large Jewish population. This all changed when Krystyna was four years old and the Soviets occupied eastern Poland, followed by the Nazis two years later. By 1943, the Chiger family had lost their livelihood, their home, and their independence, and were forced into the ghetto in the north of Lwów.

As the Nazis prepared to invade the ghetto for a final “action” in May 1943, Krystyna's father, Ignacy, led the family to a secret hiding place he had prepared with an alliance of other men in the sewers beneath their ghetto dwelling. A group of 70 desperate escapees quickly dwindled to 20 and then 10 despairing souls, enduring against all odds in a rat-infested, fetid cavern for fourteen months. The Jews survived with the devoted assistance of three Polish sewer workers. The leader of the group, Leopold Socha, was a reformed criminal who sought redemption for past transgressions through kindness to others.

The Girl in the Green Sweater is noteworthy not just for its astonishing story of escape and survival, but for the humanity and moral complexity that Chiger brings to the unlikely assemblage of people. All of their stories are told with compassion and layered with the impossible ethical dilemmas forced upon a beleaguered people. Chiger’s most empathetic reflections are dedicated to her beloved Socha, who she says, “saw us as human beings instead of as a group of desperate Jews willing to give him some money for protection.”

Most of the ten Jewish escapees rescued by Socha survived the war and went on to rebuild their lives. As of this writing, Krystyna Chiger is the last surviving member of that group. The Girl in the Green Sweater may not be appropriate in its entirety for all student audiences due to the disturbing details of survival, but it is well worth sharing select passages that convey the humanity, hope, and courage of the Jewish survivors and their rescuers. And students can view the book’s namesake – the green sweater knit by Krystyna’s beloved grandmother and which kept her warm through the years of her ordeal – at the Unites States Holocaust Memorial Museum, where it was part of a hidden children’s exhibition.

To learn more about Krystyna Chiger view her IWitness testimony, found in Echoes & Reflections teaching unit: Rescuers and Non-Jewish Resistance.

About the reviewer: Scott Hirschfeld has worked as an elementary and middle school teacher in the New York City schools and has led social justice education programs for several leading non-profit organizations, including ADL. Scott is currently a freelance diversity and anti-bias educator based in New Jersey and is part of the team working to update the Echoes & Reflections lesson plans and teaching units.

CLASSROOM LESSONS

TEACHING

Recent innovations in Holocaust education empower teachers to create memorable—even life-changing—pedagogies that were not conceivable a decade ago. Cutting-edge technologies offer powerful pathways to achieve key learning aims and outcomes, while grabbing the attention of students who crave new experiences in their learning. However, like all Holocaust education resources, these technologies require a conscientious touch and careful framing to maximize their learning potential and ensure students are prepared.

USC Shoah Foundation and Echoes & Reflections believe that pedagogical goals must come first—and that advances in technology should only be applied in service of considered educational outcomes. In genocide education—especially when working with personal stories entrusted to us by survivors—it is paramount that technology and innovation are only wielded to amplify a survivor’s message, and that they never distort or decontextualize the storytelling.

Keeping the above context in mind, below are several innovative resources available to Echoes & Reflections educators:

Newly available in IWitness, Dimensions in Testimony allows students and educators to ask questions that prompt real-time responses from a pre-recorded video of Holocaust survivor Pinchas Gutter—engaging in a virtual conversation from their own computers, and redefining what inquiry-based education can be. Through Dimensions in Testimony, it is possible to speak with survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust and other genocides from anywhere—and that possibility will remain in perpetuity.

Each student’s responses will be wholly unique because each student chooses and asks their own questions. As such, Dimensions in Testimony offers students an unprecedented degree of control over their learning—resulting in deep, empathetic engagement with subject matter.

The Willesden READS Program engages students through the story of Lisa Jura, who was rescued from the Holocaust in Vienna by the Kindertransport. This program has a rich history of in-person engagements: author, performer and virtuoso concert pianist Mona Golabek has shared her mother’s story on stage for over one million students around the world. But facing the COVID-19 pandemic, Mona partnered with Echoes & Reflections, USC Shoah Foundation and Discovery Education to transform the program into a livestreamed, remote event, thereby bringing Willesden READS to students and teachers in select cities across the United States in spite of the global health crisis.

Even before this new adaptation, the Willesden READS Program had always been a creative force on the cutting edge of Holocaust education. Fusing multiple media—the book, The Children of Willesden Lane, alongside the live performance and a series of learning engagements beyond.

The Echoes & Reflections interactive timeline—designed foremost for student use—chronicles key dates in the history of the Holocaust, spanning from 1933-1945. With the Timeline of the Holocaust, students explore history through the collective expertise and primary source archives of ADL, USC Shoah Foundation and Yad Vashem, who have constructed an approachable, tactile learning tool that centers on primary sources and individual experiences to ensure that the human impact of the Holocaust is never forgotten.

The Timeline of the Holocaust is designed to be flexible and meet the needs of educators across their curriculum. It can be a resource for students and educators to consult, or it can be the foundation of a multi-day research project.

4. We Share the Same Sky Podcast

Produced by USC Shoah Foundation and listed as one of HuffPost’s best podcasts of 2019, We Share The Same Sky brings the past into the present through a granddaughter’s decade-long journey to retrace her grandmother’s story of survival. We Share The Same Sky tells the two stories of these women—the grandmother, Hana, a refugee who remained one step ahead of the Nazis at every turn, and the granddaughter, host Rachael Cerrotti, on a search to retrace her grandmother’s story.

Experienced Holocaust educators at Echoes & Reflections and USC Shoah Foundation have built a series of bold educational resources to support this pioneering podcast which intimately confronts the Holocaust’s intergenerational impacts and explains what its legacy can tell us about our world today.

5. IWalk

USC Shoah Foundation’s first mobile application, IWalk (available in the App Store and Google Play), offers visitors and students curated tours that connect specific locations of memory with testimonies from survivors and witnesses of genocide, violence and mass atrocity. IWalks are carefully curated by USC Shoah Foundation’s team of educators and scholars who help contextualize and humanize the history at sites of memory through testimony, photographs, and maps.

Educators in the United States currently have access to a series of IWalks in Philadelphia, which create potent multimedia learning experiences for students, educators and community members who visit the Horwitz-Wasserman Holocaust Memorial Plaza.

So much more is on the horizon at Echoes & Reflections and USC Shoah Foundation, and we cannot wait to share. We have already arrived at the future of Holocaust education, and it’s ready for use in your classroom—today.

About the author: Greg Irwin is Head of Content Management on the Education team at USC Shoah Foundation – The Institute for Visual History and Education. He is the Institute’s partner lead for Echoes & Reflections, and manages both the Echoes & Reflections and IWitness websites, as well as the IWalk mobile application.

CURRENT EVENTS

TEACHING

When it comes to the Holocaust, is it appropriate to make comparisons to current events? While not a new phenomenon, many individuals invoke imagery and language traditionally associated with the Holocaust to describe or address contemporary events and personalities and educators often wrestle with the question of how comparisons can or should be made in the context of their teaching.

We had the honor of discussing this very issue with Professor Yehuda Bauer, world-renowned historian and Holocaust scholar, and Academic Advisor to Yad Vashem. What follows is an abridged version of our conversation:

Q: Teachers today often have difficulty knowing whether they can make comparisons between the Holocaust and current events. What advice can you give them?

A: One has to remember that all historical comparisons have to be based on two things: 1) the parallels between two events, and 2) the differences. When you do not mention the differences between two events then the fact that there are some similarities is meaningless. Comparison is the toolkit of every historian and we do it all the time. However, we must make it very clear that we not only compare the parallels but also the differences. Teachers must explain the comparisons and the historical context very carefully.

You have similar comparisons all the time: everything bad is compared to the Holocaust or to the Nazis. That in itself is not such a bad thing. It is a good thing to realize that Nazism is bad. However, teachers have to clearly explain to their students that comparisons have to be very carefully examined with knowledge and with understanding. Do not deny the fact that historical comparisons are important and possible, but they have to be weighed very carefully to make students aware that they must look at events and comparisons in a historically balanced way.

The fact that the Holocaust is such a central issue in so many places is because it is still the unprecedented genocide. It can happen again – not in exactly the same way because nothing is repeated in exactly the same way but, after the Holocaust, there were genocides where the perpetrators consciously learned from the Nazis, like in Rwanda.

When you study the Holocaust, you can take certain dilemmas from it and transpose them very, very carefully and show parallels.

Q: Recently, Arnold Schwarzenegger made a video after the insurrection on the U.S. Capitol where he made comparisons to his experiences growing up in Austria and the build-up to Kristallnacht[1] with what happened on January 6, 2021. What are your thoughts on this analogy?

A: Arnold Schwarzenegger’s statement was, without doubt, made with the best of intentions. However, comparing the events at the Capitol building to Kristallnacht is absolutely false.

Certain parallels can be made with the past and, with careful consideration, the lesson to be learned in this case is the defense of democratic values, which was missing in Germany. Abandonment of democratic values should be prevented in democratic countries like the United States. We have to fight for these democratic values. The parallel in this situation - the dangerous parallel – is the global rise of nationalism, segregation, and dictatorships and the anti-liberal, authoritarian regimes that are taking over in more and more places in different ways.

When comparing the past to the present, be very careful.

Q: The connections being made by teachers are not necessarily always related to other genocides but sometimes relate to modern-day political events. For example, some people compared the treatment and incarceration of asylum seekers and refugees at the southern US border last year to concentration camps in Germany in the 1930s. Is this a valid comparison?

A: Again, a comparison like this must be made very carefully. In other words, there are certain elements that are parallel, sure, but also significant differences. When the Trump administration not only prevented, or tried to prevent, the immigration of Latin Americans into the United States and separated children from their parents, there is no exact comparison between that and what happened in Germany in the 1930s because the Germans never faced any question of immigration into Germany. The question was whether they would allow any emigration from Germany - not only for Jews but also for all opponents of the Nazi regime.

In addition, the comparison of US policy at the border to “concentration camps”, which caused a big furor, was made without considering what the purpose of the German concentration camps was, historically. [Ed.: These camps exploited prisoners through harsh forced labor, and two of the concentration camps also functioned as death camps at which Jews were murdered].

Q: Let’s address the issue of relevance. Many students have no personal connection to the Holocaust, either because they are not Jewish or, geographically speaking, because the Holocaust happened in Europe, which seems far away. We know that the Holocaust was a watershed event in human history, not just Jewish history. How do we bring more meaning and relevance to our lessons? Is it helpful to use contemporary issues to teach the Holocaust?

A: The answer is yes, very clearly. What educators need to do is to emphasize that the whole world was involved in World War II, which was a war against the Nazi regime, whose ideological centerpiece was the persecution of the Jews. The Nazis said it themselves. In Hitler’s view, World War II was a war against the Jews and documents exist to prove this. However, Nazism endangered the whole world amongst other things in its hatred of Jews. Therefore, the Holocaust is relevant to everyone and we have to teach it.

[1] Kristallnacht, or the November pogrom, was a violent, State-sponsored attack against the Jews of the Third Reich (Germany, Austria and the Sudetenland) beginning on the night of November 9, 1938. More than 1,400 synagogues were torched; approximately 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps, and at least 91 Jews were murdered. https://timelineoftheholocaust.org/?evtyear=1938&evtmonth=11&evtday=9

About the authors: Sheryl Ochayon is the Director of Echoes & Reflections for Yad Vashem and Sarah Levy is the Program Coordinator for Echoes & Reflections at Yad Vashem.

CLASSROOM LESSONS

TEACHING

UNCATEGORIZED

The Holocaust is not solely a European event but a human catastrophe that altered all of history including the history of the U.S. Too often we relegate the Holocaust to a foreign event or limit the involvement of the U.S. as victors and liberators only. As we hope to instill knowledge and help our students develop into global citizens, we must approach U.S. history as intertwined with the history of the Holocaust. Although there certainly is not enough time in your curriculum to fully investigate the Holocaust in a U.S. History class, there are several opportunities to inject its lessons while also presenting a more nuanced and deeper understanding of the U.S. during this time period and the role it played in defeating Nazism. Here are a few overarching concepts with supporting teaching tools to deepen your students’ knowledge of U.S. history, the Holocaust and, more broadly, human history:

1. Teach that Antisemitism was and is not a European Phenomenon but a Human Plague, with Deep Roots in U.S. History that Continues to Pervade Today's Society.

America’s history of racial terror is not news. From the stain of slavery to various anti-immigrant movements throughout its history, antisemitism has also been present. Connect white supremacist thinking, racial pseudoscience, and the growing eugenics movement of the late 19th century with rising antisemitism in Europe. Reference the pro-Nazi German American Bund that was formed in the U.S. in the early 20th century and use events and imagery that depict the growing antisemitism that happened in the U.S., like the Night at the Garden in 1939, which is referenced in this handout in our Gringlas Unit on Contemporary Antisemitism. Utilize resources like History Unfolded and Americans and the Holocaust from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum to analyze what the average American knew about what was happening in Europe and how they felt about the events.

Highlight that while antisemitism and racism were being defeated in Europe, these hateful ideologies continued to exist in the U.S. Study the Double V Campaign and elevate the stories of Black soldiers serving in segregated units, some of which became liberators like Paul Parks. Challenge your students to analyze the ethics of American war tactics, including the firebombing of cities like Dresden and their decision not to bomb Auschwitz.

Expand your students’ understanding of who a perpetrator or a bystander is to include nations. Analyze why the U.S. restricted immigration, including the rejection of the Wagner-Rogers Bill in Congress and the M.S. St. Louis when it was stranded at sea off the coast of Florida. Examine the “paper walls” that made immigration so difficult and what the State Department did to make it nearly impossible for Jews to escape Nazi Germany. Balance these failures to rescue Jews with what the U.S. did to help Jews, like the creation of the War Refugee Board in 1944.

2. Utilize Timelines and Historic Events to Contextualize U.S. History with the Holocaust

Activate students’ prior knowledge of U.S. history, including their own family history, to help contextualize the events of the Holocaust. We want our students to become global citizens and recognize how events in the U.S. impact the rest of the world and vice versa. Consistently make these connections to broaden your students’ perspectives on the global nature of history. For example, the Great Depression of the 1930s was a global economic downturn, not just an American one, and it had wide-reaching repercussions. By December 7, 1941, the “Final Solution” had already begun with the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union six months earlier on June 22, 1941. By the time the U.S. invaded mainland Europe on D-Day, June 6, 1944, five million Jews had already been murdered. These references can help students better understand the role of the U.S. during the Holocaust, and to consider how the country's actions today might also have a larger global impact.

3. Use a More Global Approach when Studying Postwar Events

Remember to understand history as a continuum of events. Situate the Holocaust in the broader context of European History, U.S. History, and World War II by teaching about postwar actions: from the role of the U.S. in the Nuremberg Trials to its handling of displaced persons under the stress of the impending Cold War. Looking domestically, the return of soldiers and the influx of immigrants fleeing a destroyed Europe had a major impact on the U.S. in the 1940s, ‘50s, and beyond. Our webinar, Exploring Migration Before and After the Holocaust, is a great place to start examining this topic.

This is not a comprehensive list nor is it possible to weave all these points into your U.S. History class. However, they can help you search for connecting themes and opportunities to expand your students’ perspectives, engage their minds to ask questions and think critically, and help develop them into global citizens.

About the author: Jesse Tannetta is a former high school teacher who is now the Operations and Outreach Manager for Echoes & Reflections. He holds a master’s degree in Holocaust and Genocide Studies and is a current Ph.D. student beginning his dissertation on female concentration camp guard Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan.

CLASSROOM LESSONS

TEACHING

Good questions are essential to sound pedagogy and solid teaching. As teachers, we spend countless hours creating questions for exams and structured discussions. We even construct questions spontaneously during dialogue with students, hoping to generate critical thinking and deeper cognition. At Echoes & Reflections, our pedagogy guides us to encourage inquiry-based learning; the best way to do this is to inspire students to create their own questions and drive their own learning. Here are five tips to do just that:

1. Make Question Asking the Norm

One of the tenets of our pedagogy is to ensure a supportive learning environment. We often discuss this in terms of “Safely In and Safely Out” when studying the horrors of the Holocaust. However, there is so much more to creating a safe, trustworthy, and fun environment in the classroom. Do more to encourage questions than just for clarity. Challenge students to think deeper and more critically: just because you are the teacher does not mean that information presented cannot be critiqued, challenged, and discussed. Welcome these questions as an opportunity to facilitate learning through discourse.

2. Model Good Questions

Creating a culture that encourages questions includes consistently providing examples of good questions. Students typically do not focus on the quality of questions; they focus on answers. Incorporate good questions into your lessons. If at first, they don’t come from the students, they must come from you. This is especially necessary at the beginning of the year. Good questions build on prior knowledge, expand perspectives, and challenge students to think in more depth. For example, in our Nazi Germany unit, we ask: “What was the significance of the destruction of cultural institutions, such as synagogues? What message did this communicate to Jewish people? To German society more generally?” Many of our other units include essential questions to guide you in helping students to ask good questions on Holocaust topics.

3. Have Students Construct their own Questions and Provide Feedback

The ability to ask good questions is a skill that needs to be practiced, fine-tuned, and requires feedback. Students should be consistently tasked with creating their own questions. This is a great addition to a homework assignment that can serve as solid prep work for a class discussion. Teach students how to develop good questions by giving them concrete and critical feedback to hone this valuable skill set.

4. Ask Clarifying Questions and Dig Deeper into Student Responses

We want students to do more than remember or understand a concept; we want them to think critically, defend their position, and analyze the information being presented. Do not be satisfied with a simple answer to a question but probe deeper, ask clarifying questions, and provide other students the ability to chime in, voice their thoughts, and learn together. This is demonstrated in our Document Analysis handout which challenges students to explain their answers, infer from what they’ve learned, and drives further student inquiry. It provides a helpful blueprint into how to incorporate these techniques into your classroom discussions.

5. Embrace the Silence

Silence can be uncomfortable, especially for our students who are constantly inundated with media, noise, and distractions. If we want students to think critically and deeply, we need to give them time to do just that. Embrace the uncomfortable silence: your students are thinking and that is exactly the reason we asked a question in the first place.

For more insight on how to support asking good questions, join Echoes & Reflections webinar on 4/6 where we will address questions submitted by students to serve as a springboard to open up important classroom conversations that are vital to Holocaust education.

About the author: Jesse Tannetta is a former high school teacher who is now the Operations and Outreach Manager for Echoes & Reflections. He holds a master’s degree in Holocaust and Genocide Studies and is a current Ph.D. student beginning his dissertation on female concentration camp guard Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan.

This site contains links to other sites. Echoes & Reflections is not responsible for the privacy practices or the content of such Web sites. This privacy statement applies solely to information collected by echoesandreflections.org.

We do not use this tool to collect or store your personal information, and it cannot be used to identify who you are. You can use the Google Analytics Opt-Out Browser Add-on to disable tracking by Google Analytics.

We currently do not use technology that responds to do-not-track signals from your browser.

Users may opt-out of receiving future mailings; see the choice/opt-out section below.

We use an outside shipping company to ship orders. These companies are contractually prohibited from retaining, sharing, storing or using personally identifiable information for any secondary purposes.

We may partner with third parties to provide specific services. When a user signs up for these services, we will share names, or other contact information that is necessary for the third party to provide these services.

These parties are contractually prohibited from using personally identifiable information except for the purpose of providing these services.

1. You can unsubscribe or change your e-mail preferences online by following the link at the bottom of any e-mail you receive from Echoes & Reflections via HubSpot.

2. You can notify us by email at info@echoesandreflections.org of your desire to be removed from our e-mail list or contributor mailing list.

English

English