As this school year comes to a close—another surrounded by the devastating impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, increased violence and hate against the AAPI community, rising antisemitism, and other acts of racial injustice—members of our community share recommended books about the Holocaust, featuring stories of rescue, resistance, hope, and humanity in the face of tragedy, that may be a source of inspirational reading material over the summer months.

The Bielski Brothers: The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Built a Village in the Forest, and Saved 1,200 Jews

By Peter Duffy

Reviewed by Lynne R. Ravas

The Echoes & Reflections resource Students’ Toughest Questions helps  educators prepare informed and thoughtful responses to challenging topics addressed in the classroom. The question, “Why didn’t the Jews fight back?” is one I heard repeatedly from my students, their parents and guardians, colleagues, and other interested people. Understanding life in a shtetl in Eastern Europe in the 1930s can be difficult for adults and students who have little exposure to lifestyles and religious traditions. Television, movies, and books about the Holocaust and Jewish life do not always address in depth the religious and moral beliefs of the victims. The Bielski Brothers: The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Built a Village in the Forest, and Saved 1,200 Jews by Peter Duffy presents the decisions and reasonings when a group of Jewish people did choose to fight back. Furthermore, their main priority was keeping all the Jews who sought safety with them alive. The philosophy, as expressed by Tuvia Bielski, was: “Don’t rush to fight and die. So few of us are left, we need to save lives. It is more important to save Jews than to kill Germans”. Duffy helps the reader understand these choiceless choices the Jewish people faced as well as the decisions they ultimately made. The reader is exposed to the harsh realities of how to fight back and save fellow Jews while weighing the religious beliefs as well as the moral beliefs of individuals and groups. As an educator, understanding what decisions were made under those particular circumstances will help students better comprehend the realities of fighting back and the power of spiritual resistance.

educators prepare informed and thoughtful responses to challenging topics addressed in the classroom. The question, “Why didn’t the Jews fight back?” is one I heard repeatedly from my students, their parents and guardians, colleagues, and other interested people. Understanding life in a shtetl in Eastern Europe in the 1930s can be difficult for adults and students who have little exposure to lifestyles and religious traditions. Television, movies, and books about the Holocaust and Jewish life do not always address in depth the religious and moral beliefs of the victims. The Bielski Brothers: The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Built a Village in the Forest, and Saved 1,200 Jews by Peter Duffy presents the decisions and reasonings when a group of Jewish people did choose to fight back. Furthermore, their main priority was keeping all the Jews who sought safety with them alive. The philosophy, as expressed by Tuvia Bielski, was: “Don’t rush to fight and die. So few of us are left, we need to save lives. It is more important to save Jews than to kill Germans”. Duffy helps the reader understand these choiceless choices the Jewish people faced as well as the decisions they ultimately made. The reader is exposed to the harsh realities of how to fight back and save fellow Jews while weighing the religious beliefs as well as the moral beliefs of individuals and groups. As an educator, understanding what decisions were made under those particular circumstances will help students better comprehend the realities of fighting back and the power of spiritual resistance.

For more information on the Bielski Brothers, educators can also view this article from Yad Vashem.

About the reviewer: Lynne Rosenbaum Ravas retired from teaching and began presenting with the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh’s Generations Program. In addition to serving as a facilitator for Echoes & Reflections, she volunteers with the Federal Executive Board’s Hate Crimes Working Group, FBI’s Citizens’ Academy, and other organizations in the Pittsburgh area.

Stories about Dita Kraus, the “Librarian of Auschwitz”

Reviewed by Kim Klett

I must confess; I typically avoid any recent book that has the name “Auschwitz” in it. Look at what American publishers did to Primo Levi’s incredible If This is a Man, changing the title to Survival in Auschwitz, as if readers wouldn’t understand the original title. Lately, I have seen too many poorly written, poorly researched novels on Auschwitz, and my guess is that publishers believe the name Auschwitz will sell copies, since there is an interest in Holocaust and WWII-related books. Recently, though, I had several readers tell me how much they liked Antonio Iturbe’s The Librarian of Auschwitz. I was surprised to find it in the young adult section at my favorite local bookstore, but immediately liked the fact that it names the librarian of the title, Dita Kraus, on the front cover. A few pages in, I was hooked. Iturbe did his research, telling a much broader version of what I had heard about Birkenau’s “family camp,” which consisted mostly of Czechoslovakian Jews, among them Dita Kraus, a 14-year-old girl there with her parents. The “library” consisted of eight books, all taken from suitcases on the ramp, and each lovingly taken care of and hidden away, except when it was safe to share them. Readers witness the selections that take place in this special camp, the interactions with the notorious Mengele, and daily life for some of the children there. The narration is beautiful, reminding me a little bit of The Book Thief; it definitely keeps the pages turning. Iturbe also includes a postscript, explaining how he got the information and what happened to the people whose lives unfold in the book. This is where I started searching for more books on the topic, and also highly recommend Dita Kraus’ beautiful memoir, A Delayed Life: The True Story of the Librarian of Auschwitz. While the memoir does not say a lot about her time in the “family camp”, it is rich with details of her life in Prague before the war, as well as her post-war life. I appreciate this because so many Holocaust memoirs focus mainly on the time in the camps, and while that is important, it is also crucial to see survivors’ full lives. Another book I checked out is one written by Dita’s husband, Ota Kraus, a novel called The Children’s Block. It is an interesting complement to the novel and to Dita’s memoir, but not one I would use in my classroom. I will be using both The Librarian of Auschwitz and excerpts from Dita Kraus’s memoir next year and I cannot wait to share them with my students.

“Auschwitz” in it. Look at what American publishers did to Primo Levi’s incredible If This is a Man, changing the title to Survival in Auschwitz, as if readers wouldn’t understand the original title. Lately, I have seen too many poorly written, poorly researched novels on Auschwitz, and my guess is that publishers believe the name Auschwitz will sell copies, since there is an interest in Holocaust and WWII-related books. Recently, though, I had several readers tell me how much they liked Antonio Iturbe’s The Librarian of Auschwitz. I was surprised to find it in the young adult section at my favorite local bookstore, but immediately liked the fact that it names the librarian of the title, Dita Kraus, on the front cover. A few pages in, I was hooked. Iturbe did his research, telling a much broader version of what I had heard about Birkenau’s “family camp,” which consisted mostly of Czechoslovakian Jews, among them Dita Kraus, a 14-year-old girl there with her parents. The “library” consisted of eight books, all taken from suitcases on the ramp, and each lovingly taken care of and hidden away, except when it was safe to share them. Readers witness the selections that take place in this special camp, the interactions with the notorious Mengele, and daily life for some of the children there. The narration is beautiful, reminding me a little bit of The Book Thief; it definitely keeps the pages turning. Iturbe also includes a postscript, explaining how he got the information and what happened to the people whose lives unfold in the book. This is where I started searching for more books on the topic, and also highly recommend Dita Kraus’ beautiful memoir, A Delayed Life: The True Story of the Librarian of Auschwitz. While the memoir does not say a lot about her time in the “family camp”, it is rich with details of her life in Prague before the war, as well as her post-war life. I appreciate this because so many Holocaust memoirs focus mainly on the time in the camps, and while that is important, it is also crucial to see survivors’ full lives. Another book I checked out is one written by Dita’s husband, Ota Kraus, a novel called The Children’s Block. It is an interesting complement to the novel and to Dita’s memoir, but not one I would use in my classroom. I will be using both The Librarian of Auschwitz and excerpts from Dita Kraus’s memoir next year and I cannot wait to share them with my students.

Explore Yad Vashem’s online exhibition, The Auschwitz Album, the only surviving visual evidence of the process leading to the mass murder at Auschwitz-Birkenau, to learn more about the Jewish experience in these camps.

About the reviewer: Kim Klett has taught English at Dobson High School in Mesa, Arizona, since 1991, and developed a year-long Holocaust Literature course there. She is a senior trainer for Echoes & Reflections, the deputy executive director for the Educators’ Institute for Human Rights (EIHR), and a Museum Teacher Fellow with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

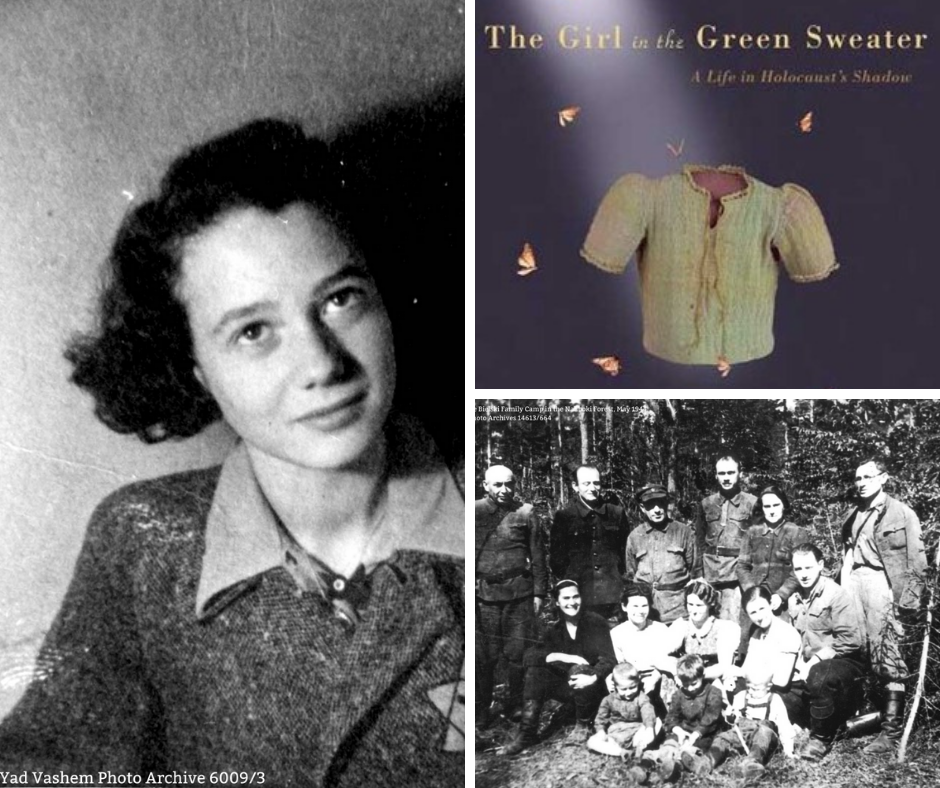

The Girl in the Green Sweater

By Krystyna Chiger & Daniel Paisner

Reviewed by Scott Hirschfeld

While searching for resources to support a lesson on extraordinary actions taken by ordinary – even flawed – people during the Holocaust, I stumbled across Leopold Socha, the Polish sewer worker and unlikely savior of a group of ten Jewish people. Socha’s story is part of a broader tale of survival recounted by Krystyna Chiger (later known as Kristin Keren) in her gripping memoir, The Girl in the Green Sweater.

taken by ordinary – even flawed – people during the Holocaust, I stumbled across Leopold Socha, the Polish sewer worker and unlikely savior of a group of ten Jewish people. Socha’s story is part of a broader tale of survival recounted by Krystyna Chiger (later known as Kristin Keren) in her gripping memoir, The Girl in the Green Sweater.

Krystyna Chiger was born in 1935 in Lwów, Poland. At age 8, she had already lived two lives. The first half resembled, in her words, a “character from a storybook fable.” The daughter and granddaughter of successful textile merchants, Krystyna enjoyed a life of privilege in the midst of a bustling metropolis with a large Jewish population. This all changed when Krystyna was four years old and the Soviets occupied eastern Poland, followed by the Nazis two years later. By 1943, the Chiger family had lost their livelihood, their home, and their independence, and were forced into the ghetto in the north of Lwów.

As the Nazis prepared to invade the ghetto for a final “action” in May 1943, Krystyna’s father, Ignacy, led the family to a secret hiding place he had prepared with an alliance of other men in the sewers beneath their ghetto dwelling. A group of 70 desperate escapees quickly dwindled to 20 and then 10 despairing souls, enduring against all odds in a rat-infested, fetid cavern for fourteen months. The Jews survived with the devoted assistance of three Polish sewer workers. The leader of the group, Leopold Socha, was a reformed criminal who sought redemption for past transgressions through kindness to others.

The Girl in the Green Sweater is noteworthy not just for its astonishing story of escape and survival, but for the humanity and moral complexity that Chiger brings to the unlikely assemblage of people. All of their stories are told with compassion and layered with the impossible ethical dilemmas forced upon a beleaguered people. Chiger’s most empathetic reflections are dedicated to her beloved Socha, who she says, “saw us as human beings instead of as a group of desperate Jews willing to give him some money for protection.”

Most of the ten Jewish escapees rescued by Socha survived the war and went on to rebuild their lives. As of this writing, Krystyna Chiger is the last surviving member of that group. The Girl in the Green Sweater may not be appropriate in its entirety for all student audiences due to the disturbing details of survival, but it is well worth sharing select passages that convey the humanity, hope, and courage of the Jewish survivors and their rescuers. And students can view the book’s namesake – the green sweater knit by Krystyna’s beloved grandmother and which kept her warm through the years of her ordeal – at the Unites States Holocaust Memorial Museum, where it was part of a hidden children’s exhibition.

To learn more about Krystyna Chiger view her IWitness testimony, found in Echoes & Reflections teaching unit: Rescuers and Non-Jewish Resistance.

About the reviewer: Scott Hirschfeld has worked as an elementary and middle school teacher in the New York City schools and has led social justice education programs for several leading non-profit organizations, including ADL. Scott is currently a freelance diversity and anti-bias educator based in New Jersey and is part of the team working to update the Echoes & Reflections lesson plans and teaching units.

English

English