When I was asked to write about love during the Holocaust, I was excited to dive into USC Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive to look for testimony to showcase this uplifting sentiment from a tragic period in history. Before I even started my research, I knew that I wanted to write about the many types of love that shined through the darkness of the Holocaust. Through stories of family, significant others, and friendships, the following testimonies highlight that love was truly a powerful force in keeping the human spirit alive during and after the Holocaust.

Family

- Eric Richmond: Parents in Nazi-occupied Europe were faced with the unimaginable choice of keeping their families together or sending their children to unoccupied countries. Later on, parents were also faced with the choice of having their children smuggled out of ghettos and being hidden with non-Jewish families. Both of these circumstances present an inconceivable choice with no right or wrong answers. But hearing survivors talk about being separated from their parents – their parents who told them they would be reunited, their parents who tried to make this seem like a big, exciting adventure – is heartbreaking. Eric Richmond, who was sent on a Kindertransport from Vienna, Austria to England, begins talking about his experience looking directly at the interviewer. The more he remembers, the less he looks at her. He’s recounting the lifesaving decision his parents made, but he’s reliving the trauma of being separated from them. No matter how many times I watch his testimony, it always affects me. Knowing what his parents did out of love, and seeing his reaction fifty years later, is a reminder of the unconditional bond between parent and child.

- Fritzie Fritzhall: When Fritzie Fritzshall was forced to do slave labor in a factory—after her mother and brothers had been murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau, after she had been separated from her aunt—she was the youngest in a group of 600 women, and now considered the other women her mothers. In her testimony, Fritzie remembers a promise she made the women to preserve their legacy, and discusses when she realized she had to tell her story to fulfill her promise. I’ve been working with Holocaust survivors for over fifteen years, and I know how hard it can be for them to tell and retell their story. I’m grateful that Fritzie was able to keep her promise, and that her story, and the story of her 599 mothers, can continue to survive.

Significant Others

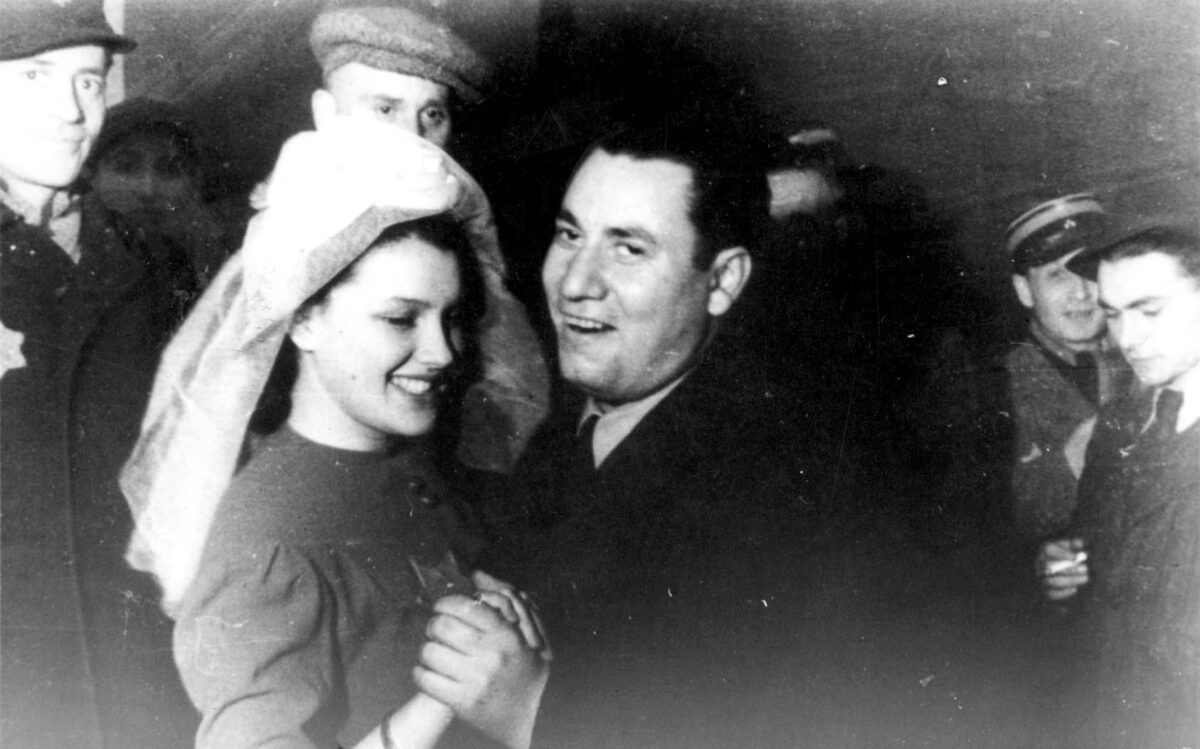

- Kurt & Sonia Messerschmidt: Throughout the archive, there are beautiful stories that describe the moment survivors are reunited with their partners. Kurt and Sonja Messerschmidt were engaged before they were deported to Theresienstadt, where they were wed. However, in 1944, they were separated, and after the war, Kurt wasn’t sure if Sonja survived. In this clip, he describes the moment he realized she survived, and he discusses the significance of the date they were reunited. I am inspired by how overcome with emotion Kurt becomes when describing what happened as it exemplifies the deep devotion he carried for Sonja.

- Gerta Weissman & Kurt Klein: Unlike Kurt and Sonja, Gerda Weissman did not know Kurt Klein before the war. However, neither she nor Kurt would forget meeting one another. Here, Gerda describes being liberated by Kurt, wondering what happened to the nice man who liberated her, and being reunited with him. The couple eventually married and immigrated to the United States. Their love is evident in both their testimonies (Kurt is also in the archive; you can hear his version of events here).

- Gad Beck & Manfred: Gad Beck had two strikes against him in Nazi Germany. He was Jewish, and he was gay. One night, when he went to pick up his boyfriend Manfred for a date, Gad learned that Manfred and some of his family members had been taken to a transit camp. Gad tells the story of what happened next in this clip. Gad’s love for Manfred was so great that he helped Manfred escape from the camp; Manfred’s love for his family led him to return to be with them. The first time I watched that clip, I didn’t expect the story to end the way it did. But I absolutely respect Manfred’s decision, even if it broke Gad’s heart. It shows the devastating complexities of the choiceless choices many Holocaust victims faced, having at times decide between one love over the other.

Friendships

- Herman Shine & Max Drimmer: Herman Shine and Max Drimmer were friends in pre-war Germany. During the Holocaust, they were reunited at Auschwitz, and the friends decided to escape. They were inseparable for the next sixty years – they had a double wedding with their wives, they immigrated with one another, and they lived close to each other in California. I am absolutely convinced that their friendship and love for one another is what got them through their hardest times.

- Bertram Schaffner & his Army Unit: After being drafted in October 1940, Bertram Schaffner worked as a psychiatrist in the U.S. Army. During World War II, when gay men were dishonorably discharged from the armed forces just because of their sexuality, Bertram – who himself was gay – helped enlisted men who he suspected were also gay by either keeping their records clean of anything that could be incriminating or honorably discharging those men who realized they did not want to serve under such discriminatory conditions. His empathy, decency and humanity shine through his entire testimony, and I’m grateful that he loved his fellow draftees to support them in extremely inequitable times.

- Roman Kent & Lala: Even pets played a strong role in offering love and devotion during the Holocaust. When Roman Kent and his family were sent to the Łódź ghetto, they had an unexpected visitor: their dog Lala. After the war, when Roman had children of his own, he used to tell them the story. In his testimony, Roman recalls Lala visiting the family every night, and reflects that “Love is stronger than hate.”

Whether through family, significant others, or friendship, it is clear that love endured and prevailed throughout the Holocaust. Let these testimonies be a reminder that love is a potent force that can inspire actions today that will build a better tomorrow.

About the author: Rachel Herman is the Content Management Specialist at USC Shoah Foundation and helps curate content for IWitness and other educational programs. Rachel received her M.A. in Holocaust and Genocide Studies from Stockton University.