Sites of memory illustrate the interactions, tensions, and complicated layers of how the past and present have selectively been remembered, forgotten, and silenced over time.[1] These sites and their meanings, crafted and produced by particular individuals or groups through symbolism and aspirations for how the site should be understood, are malleable, transforming and evolving within the societies in which they exist and by those who consume and interpret these sites.

“This is the site for the American memorial to the heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto Battle April-May 1943 and to the six million Jews of Europe martyred in the cause of human liberties.” -Plaque, Warsaw Ghetto Memorial Park, Riverside Park, New York City, New York

Described as a site of memory meant to “ke[ep] alive” the memory of the six million Jews who perished from what would eventually be known as the Holocaust, the Riverside Park memorial was erected in October 1947, catalyzed and envisioned by the American Memorial to Six Million Jews of Europe, Inc., as step one of a large, disruptive, contemplative space visible from the surrounding Western Manhattan, New York area.[2] In its original conception, this space was supposed to force those around to confront and reflect on the bravery of Jewish victims of the Nazi regime. Specifically seeking to memorialize the courage of Jews in the “Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto,” now traditionally referred to as the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, to denote the heroism of those who fought back despite hopeless circumstances, this memorial represents one of the first Holocaust sites of memory in the United States. However, over seventy-five years later, this memorial, known today as the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial Park, remains in its initial physical manifestation, seemingly blending into the landscape as a plaque on the ground as opposed to causing an active remembrance and education of this genocide. How does one of the first Holocaust sites of memory in the United States become just another part of a park, and how can consumers of this site and others work to elevate our understanding of hard histories?

When I visited the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial Park, I was immediately struck by the dedicated protection for the plaque. As I teach in my courses, fences surrounding sites of memory not only keep things out, but they have the potential to ‘gatekeep’ memories in. I wondered about the legacies of vandalism and natural degradation that might have brought about the need for a fence to protect the physical plaque and the people it represents as well as the experiences and identities of those who were killed in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising whose stories we might never know. I questioned if any pro-Nazi groups had ever paraded around this memorial to attempt to change its signification and celebrated the fact that even if so, the community of proponents and supporters of this site have remained steadfast in honoring the Jewish victims of the Holocaust. I thought about the Jewish tradition of leaving stones on gravesites to signify visitation and remembrance when seeing a few littered rocks on and around the plaque, curious about how this practice shifted the meaning of the site upon my visit. I reflected upon what the memorial silenced – other moments of resistance and loss fallen through the cracks because of the heightened focus of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising – and how many of the narratives of suffering and heroism, struggle and resistance during the Holocaust will never be told.

These unique interpretations emerged through my specific understanding of the Holocaust, of sites of memory, and of my fragmented knowledge about the various iterations of this site at a particular moment in time. Other visitors will consume the site in similar and different ways, due to their overlapping and contrasting knowledge base coming to this site, meaning that we all play a part in the meaning making process. In experiencing sites of memory, we all share a role in how the past and present converge, diverge, and attempt to be understood.

As a consumer in 2023, I was greatly influenced by the current moment of sites of memory in the United States. The United States has been reckoning with its own violent past and injustices, particularly the legacies of the institution of slavery and its long-term consequences on the Black population and genocide perpetrated against Indigenous communities. Demands to interrogate and dismantle the contemporary public landscape have demonstrated that monuments, memorials, and museums are being reinterpreted today, serving as representative symbols of the present and future as well as relics of the past. These historical reinterpretations have also included a deep reflection of the United States’ role in the Holocaust. The current exhibit in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., Americans and the Holocaust, and Ken Burns’s new documentary series, The U.S. and the Holocaust, challenge the traditional narrative of the United States as global liberators of concentration camps by emphasizing the xenophobia and non-interventionist mentality permeating the United States during the rise of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust. Studying various Holocaust memorials and museums in the United States causes us to question why these sites exist and how they came to fruition.

The remnants of water on the plaque created a literal reflection. While looking back and thinking about the victims of the Holocaust, the reflection also allowed me to see the branches of a tree above, symbolizing, to me, a journey of rebirth and regrowth.

Contextualizing the ideologies and erection of sites of memory allows us, as consumers, to root ourselves in the original conceptions and unavoidable evolutions of these spaces and their meanings over time. Understanding the producers and their assumed audience, along with the narratives and memories honored and silenced in these spaces, informs our experience and interpretations as consumers. The next time you see a plaque on the ground, look at it, read it, interpret it, experience it, and commit yourself to learning more about how these sites promote particular versions and memories of the past for our present and future. You are a part of the meaning making process; your interpretations matter!

About the author: Tyler J. Goldberger is a History PhD candidate and Teaching Fellow at William & Mary. His scholarship explores historical memory, human rights, transnationalism, and US-Spain relations in the 20thcentury.

[1] Maurice Halbwachs, On Collective Memory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1925); Pierre Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire,” trans. Marc Roudebush, Representations 26 (Spring 1989): 7–24.

[2] “Jewish Memorial to Rise on Drive,” New York Times, June 19, 1947.

English

English

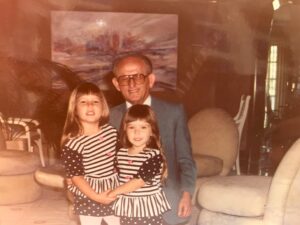

After surviving the Holocaust, then living an extraordinary life, my grandfather, Herschel (Hersi) Zelovic, lost his life to Covid-19 on November 11th at the age of 93. On this day, my grandfather was one of the 1,431 Covid-related deaths in the United States. As I am writing this blog—not even three months after his death—there have been more than 400,000 reported deaths nation-wide due to this terrifying disease.

After surviving the Holocaust, then living an extraordinary life, my grandfather, Herschel (Hersi) Zelovic, lost his life to Covid-19 on November 11th at the age of 93. On this day, my grandfather was one of the 1,431 Covid-related deaths in the United States. As I am writing this blog—not even three months after his death—there have been more than 400,000 reported deaths nation-wide due to this terrifying disease.

They married and moved to New York City, surrounded by family and friends from Europe. They built a happy life together; my mother was born, then there were grandkids, and two great-grandchildren – a life and legacy made possible after liberation.

They married and moved to New York City, surrounded by family and friends from Europe. They built a happy life together; my mother was born, then there were grandkids, and two great-grandchildren – a life and legacy made possible after liberation. Holocaust: a shift from antisemitic propaganda and policy to government-sanctioned violence against Jewish communities in Germany, annexed Austria, and in areas of Czechoslovakia that had been recently occupied by German troops. The anniversary of this event on November 9 and 10 presents an opportunity for educators to explore this history with students—to teach about the dangers of antisemitism and the role and responsibility of an individual in interrupting the escalation of hate. Furthermore, the lessons of the Kristallnacht Pogrom, only further highlight the importance of our collective duty to uphold the pillars of democracy. At a time when our nation is facing increasingly high levels of antisemitism, the lessons from the “Night of Broken Glass” can resonate deeply with students and compel them to examine the critical need to stand up to antisemitism and all forms of hate. Here are some strategies and resources to guide you in teaching this topic:

Holocaust: a shift from antisemitic propaganda and policy to government-sanctioned violence against Jewish communities in Germany, annexed Austria, and in areas of Czechoslovakia that had been recently occupied by German troops. The anniversary of this event on November 9 and 10 presents an opportunity for educators to explore this history with students—to teach about the dangers of antisemitism and the role and responsibility of an individual in interrupting the escalation of hate. Furthermore, the lessons of the Kristallnacht Pogrom, only further highlight the importance of our collective duty to uphold the pillars of democracy. At a time when our nation is facing increasingly high levels of antisemitism, the lessons from the “Night of Broken Glass” can resonate deeply with students and compel them to examine the critical need to stand up to antisemitism and all forms of hate. Here are some strategies and resources to guide you in teaching this topic:

etched into the stone throughout the Memorial, the full text of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on permanent display, the Rose Beal Legacy Garden honoring a local Holocaust survivor, a sapling from the Anne Frank Chestnut Tree in Amsterdam, the Marilyn Shuler Classroom for Human Rights, recognizing a founder of the Memorial and the state’s first director of the Human Rights Commission, and state-of-the-art electronic technology showcasing the “History of Human Rights in Idaho.”

etched into the stone throughout the Memorial, the full text of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on permanent display, the Rose Beal Legacy Garden honoring a local Holocaust survivor, a sapling from the Anne Frank Chestnut Tree in Amsterdam, the Marilyn Shuler Classroom for Human Rights, recognizing a founder of the Memorial and the state’s first director of the Human Rights Commission, and state-of-the-art electronic technology showcasing the “History of Human Rights in Idaho.” up a nine-step staircase tucked behind a marble bookcase, and the surrounding walls mirror the Amsterdam skyline.

up a nine-step staircase tucked behind a marble bookcase, and the surrounding walls mirror the Amsterdam skyline.