“I always knew I was Jewish, but in our house, there was no religion practiced really.” These are words from Holocaust survivor Margaret Lambert, describing what her life was like in Germany before Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. It’s a sentiment I can relate to as I also have always known I was Jewish. There was never any need to give intentional visibility to this identity through custom or tradition. My non-English name ascribed to me at birth, given out of remembrance, to hold onto what my mother left behind in her homeland, instilled in me an immutable awareness of my cultural roots.

The “always knowing” clings more tightly as a third-generation survivor, as the Holocaust has also always been a part of unconscious memory. I don’t recall a moment during a classroom lesson, watching a movie, or in conversation where I first acquired knowledge about this catastrophe—it is one that has always been with me, a specter of my past. My maternal grandfather’s survival story was ever-present in my childhood. It was a tale drenched in the heroism and bravery of a young man who fled Poland (now Belarus) by sea to Palestine in 1937, illegally jumped ship and joined the British army as a spy to fight against the Axis powers—forces that would be responsible for the deaths of so many of my other relatives. It never eludes me that my very existence, my ability to live freely and have endless opportunities in this country, is a result of his fortuitous escape.

In some ways I am envious of those who have had the privilege to be introduced in a well thought out and planned way to this pivotal history. That there are those who can pinpoint a specific moment when they learned about the Holocaust, designating a before and after, a division of this time in their lives. These are people who have a mechanism to assess their perspective on humanity prior to knowing vs. now having the knowledge cemented, which can hopefully offer deeper reflection on the timeless lessons of this history.

It’s not that I don’t have memories about moments of witnessing, experiencing an awareness of the Holocaust, or that it wasn’t ever presented to me in a classroom setting, but they often are fraught with discomfort—it feels at times too personal. When I was 10 years old, I visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and wandered through Daniel’s Story—on my own. I distinctly remember entering the concentration camp section of the exhibit, my lungs filling with a heavy cold air, a sudden suffocation of dread and panic, the thought of “this could have been me” creeping through my mind. I raced out of there as fast I could, wanting to shed whatever memory or passed down trauma I may have inadvertently absorbed. This is not because Daniel’s Story is one that should not be viewed by young people, but it does make me wonder if there are deeper considerations as to how a generational survivor might be impacted by certain Holocaust learning experiences.

Despite the challenges of remembrance, there is the question of responsibility. What is my duty to share, uphold, the memories of a story, that isn’t really my own lived experience, but one that seems to reside firmly in my DNA? “Never Forget” has been, still is, and will always be a reverberating phrase in my consciousness. While there is no clear beginning to the memory, the not forgetting is the foundational tenet of my Holocaust education. I firmly believe in this notion, but over the years I have encountered a tension between the “knowing” and the actions I am expected to take with this knowledge, particularly if it involves sharing my own ancestral trauma. Perhaps it’s because I don’t want myself or my family to be defined by tragedy, by the weight it inevitably carries.

And yet, the work I do is a reminder that the action of remembrance can take different forms. I may not be openly sharing my family’s history on a regular basis, but it is because of my background that I feel an unexpected comfort, sense of ease even, in being one to support educators and students in learning about the Holocaust. I am contributing to a program that provides Holocaust education in a responsible and effective manner, which perhaps is my own way of moving “safely in and out”—an experience I severely lacked in my youth. And, with time, almost six years at this point, I am beginning to allow more of the personal to seep into the work, like seeing myself through Margaret, or through the multitude of visual history testimonies our program provides. It is perhaps through this ongoing experience, that at some point I will be able to move towards a greater security to openly share my family’s Holocaust story.

About the author: Talia Langman is the Media & Communications Specialist for Echoes & Reflections.

English

English

After surviving the Holocaust, then living an extraordinary life, my grandfather, Herschel (Hersi) Zelovic, lost his life to Covid-19 on November 11th at the age of 93. On this day, my grandfather was one of the 1,431 Covid-related deaths in the United States. As I am writing this blog—not even three months after his death—there have been more than 400,000 reported deaths nation-wide due to this terrifying disease.

After surviving the Holocaust, then living an extraordinary life, my grandfather, Herschel (Hersi) Zelovic, lost his life to Covid-19 on November 11th at the age of 93. On this day, my grandfather was one of the 1,431 Covid-related deaths in the United States. As I am writing this blog—not even three months after his death—there have been more than 400,000 reported deaths nation-wide due to this terrifying disease.

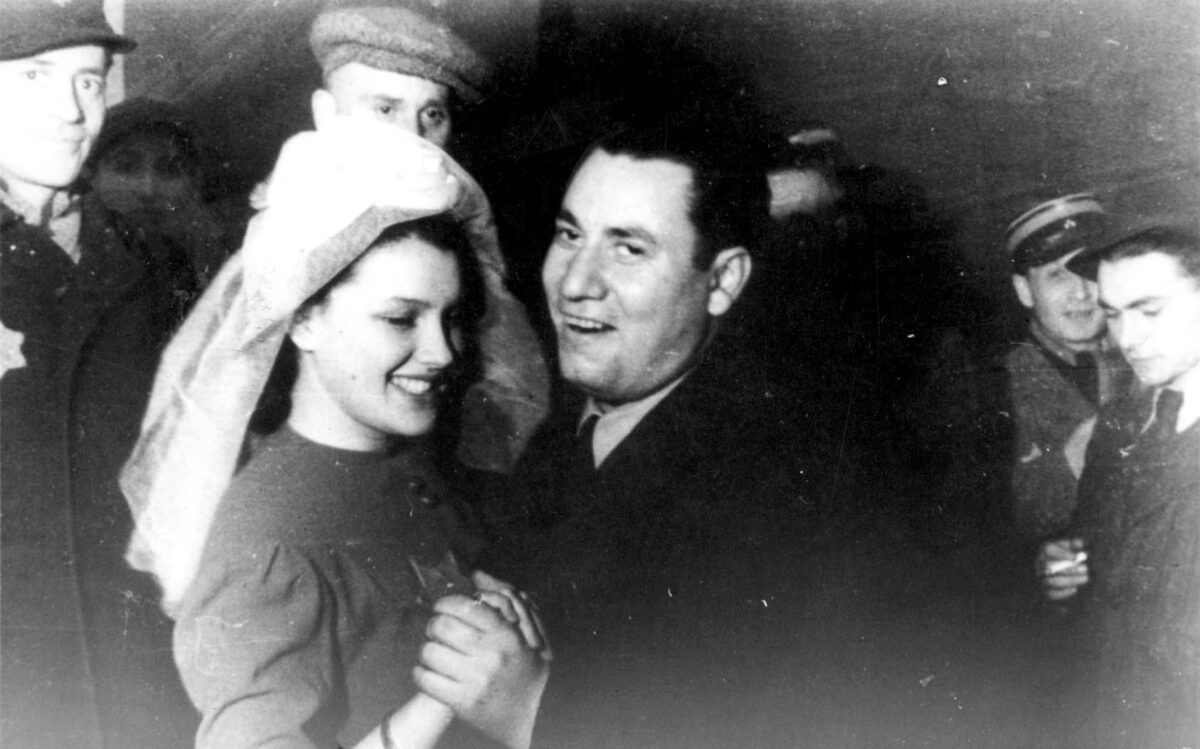

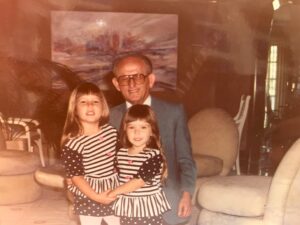

They married and moved to New York City, surrounded by family and friends from Europe. They built a happy life together; my mother was born, then there were grandkids, and two great-grandchildren – a life and legacy made possible after liberation.

They married and moved to New York City, surrounded by family and friends from Europe. They built a happy life together; my mother was born, then there were grandkids, and two great-grandchildren – a life and legacy made possible after liberation.